All communities have identities built around core principles. I’ve learned over the last few years that the traditional art world tends to value, promote, and embrace scarcity, and as a result, often finds that there are not enough resources to go around. It is noteworthy to me that communities that promote abundance, sharing, and generosity, such as the generative art community, often find that they have all of the resources and support that they need and more.

Kjetil Golid embodies the generative art ethos. Golid open sources all of his code for other artists to learn from. Further, he has built an amazing set of free tools on his website that makes it easy and fun for anyone to manipulate his algorithms, producing brilliant visuals and opening the door to generative art.

One of the things I really enjoy about Golid is how down to earth he is. He mostly creates art for fun, and the joy of creation comes through in his work. It was a pleasure to interview him for “The Game of Life - Emergence in Generative Art” exhibition currently running online at the Kate Vass Galerie. I hope you enjoy the interview as much as I did.

INTERVIEW

JB: It’s great to meet you, Kjetil. I’ve been following your work for a long time and I’m a big fan, and I appreciate you taking the time to chat.

KG: Yeah, great. Thank you.

JB: Where are you located?

KG: I’m located in Trondheim in Norway. It is a city in the middle of Norway.

JB: Born and raised there, your whole life?

KG: No, I actually come from a small village in the south of Norway. I moved here after I finished studying at the university.

JB: Did you study computer science? Was that your academic background?

KG: Yes. I actually took a bachelor’s in cognitive science, and I specialized in computer science afterward for my master’s degree.

JB: I’m always interested when I talk to folks that operate at the intersection of art and technology to understand their background in terms of which came first, programming or art, or if they kind of progress at the same time. How would describe your progression in terms of your interests?

KG: I would say it’s from the math side. Actually, I started a bachelor’s degree in graphic design first. It was there where I got introduced to Processing, the programming language. But I didn’t really make a lot of it. I quit the design school and I started cognitive science. Later on, I studied computer science where I developed a fascination for structures and systems, like Turing machines and the regular languages, deduction systems and everything, which was also what I wrote my thesis about. I used programming as sort of a tool to visualize and understand these different concepts.

From there, I found out that introducing things like randomness and different kind of data sets would make some interesting results.

Cross Hatch Automata - 2020, Kjetil Golid

JB: That’s fascinating. Around what year did you first use Processing?

KG: I took graphic design in 2011, but I didn’t know anything about programming back then. It wasn’t until maybe a couple of years later that I started actually doing some notable works in Processing. But I was also just messing around and experimented doing things in order to learn various programmatical and mathematical concepts.

JB: Wow. I look at your work and I’m always blown away. I don’t consider myself a very strong coder, but even my brother, who is a developer, has a lot of respect for the work that you produce from a technical standpoint. I obviously look at it more from the art side, although I have some programming background.

Was it through school that you learned the Processing programming language or were you largely self-taught? Was it through other artists’ code? Perhaps a combination?

KG: It was mostly from school. I learned Java in university. Processing is Java-based, so it’s basically a simpler version of Java. So mostly from there.

Then I learned some more of these visual techniques and methodologies from Daniel Shiffman.

JB: Oh, yeah. Dan’s great!

KG: And various other people that have made a lot of visual work.

JB: You seem -- in the best way possible -- very generous with your code. I love how you produce interfaces that people can play around with. A lot of artists just produce the work, and sometimes even actively try to hide how they are making it. It seems like you are compelled to share your code and how your how artwork is created. Does that come from having benefited from other people? How do you think about open-sourcing code and sharing?

Hatch Automata Rotate - 2018, Kjetil Golid. Go play with it! It’s a ton of fun!

KG: I think I kind of owe it to the world since my own progression has been so dependent on the generosity of others, so I feel like it’s only natural that I open source my work. It leads to some weird cases where what I sell to people is actually open-source. Not even just to download for free, but to actually generate the work themselves, to generate however many examples they would like. Even then, I think it’s great to see people downloading the code and continuing the work, making their own reimaginations of things. I think that’s really great to see.

JB: That’s great to hear. The only reason I was able to learn programming is because I learned from examples by folks like Casey Reas and Jared Tarbell in the early 2000s. So many of my friends that, like me, come from traditional art backgrounds would never have learned any programming at all if it weren’t for their generosity.

Now that the art market seems to be taking an interest in generative art, I worry that some artists are getting more protective of their code than they used to be. There was no opportunity to make money before, so there was no reason to hide your code. But now that it’s opening up, I feel like there’s a trend towards people protecting their code instead of sharing it.

Why would you think someone would buy it if they could download the code and produce it for free?

KG: Well, the closest comparison would be to download music and movies and whatnot. You can always do that, and it's obviously free. But maybe the art world would need to see this change, also, that buying work is not about obtaining just the visual stuff. Of course, you can download the Mona Lisa. But that is not the same as buying it. Especially on the CryptoArt scene. Getting the actual token is kind of like my signature on the work and it would be a completely different thing if you just downloaded it for free.

Invade 1 - 2020, Kjetil Golid

JB: I agree. Hopefully there’s a new breed of collectors that will come along that are less obsessed with owning the physical object and having something that no one else can own and want to collect to help support the creation of more work, too. That would be the ideal. Maybe we’re slowly moving in that direction.

Not a lot of the generative artists that I’ve spoken to or am friends with have necessarily embraced the crypto or blockchain art world just yet -- although, I’ve personally been very interested in that space for a while. What’s your experience been like? I know you’ve been on KnownOrigin for a while, and now SuperRare, as well.

KG: It’s kind of random that I ended up on KnownOrigin. I hadn’t really looked into it much until I got approached with an offer to join. I didn’t really think a lot about it. I just added some of my stuff there. I find it to be an interesting concept now with all the -- maybe this can be the way we actually distribute digital art. I really don’t condemn other people for not joining here, and as I said, it’s really just by chance that I ended up there myself. I don’t really take my artwork -- it’s not this very serious thing for me, really, so I think it’s just kind of fun.

Curvescape 1 - 2018, Kjetil Golid

JB: It sounds like you produce your art for the joy of producing your artwork. You’re not necessarily trying to become a world-famous artist or something like that. Would that be fair that it’s really about the making process and the ability to share with others that drives you?

KG: Yeah, definitely. As I said, I started this to learn concepts in the first place and mess around with different structures and learn different algorithms. At some point, I figured that you could make these things quite beautiful and really emphasize the interesting parts of the algorithms by using colors and shapes. I really didn't think that this would end up as something I can print and put on a wall and stuff like that. But then it did end up going that direction. I don’t think my motivations have changed.

JB: That seems like a healthy way to look at it, especially if it keeps you producing work.

Maybe you haven't thought about this side as much, but another question that changes, it seems like, from artist to artist is whether or not they consider the code itself to be the artwork or the output of the code. Given that generative art can produce so many variations and versions on a similar theme, do you see the individual images or the code that produces them as the art? In the old days, you made a painting and there was one painting or a print and there were a limited number of those prints, and the physical output was the thing you would purchase and hang on your wall. But I think more and more, it seems like some of these generative artists are thinking, well, the code is the artwork, and I built the system and the system is the artwork more so than the output. Have you thought about that much? Where would you land on that?

KG: I definitely won’t consider my code the artwork. That is not art by any means. [laughs]

JB: [laughs]

KG: Yeah, I think I would consider the system the artwork, if anything, because, as you know, I post a lot of my stuff on Twitter and Instagram. I rarely post a single instance of something I created. I post several because I feel like part of the expression is the variation in between those instances, and posting or releasing or publishing only one of those instances, something would be missing from that. So maybe the generator itself or the system, as you said.

JB: I really appreciate that you show the variations because I feel like it gives me a window into your process when you can see multiple variations on each work. I think some artists artificially limit how much work they put out there because they’re worried about trying to make it scarce or rare so that they can drive up the value of it. But as an artist myself, I know that the process is arguably the most important part. And as an art appreciator, being able to go on that journey with someone enriches the experience. I really enjoy that you’re as open as you are and show the different variations.

Sometimes people who don’t know how to program think that since a program can run the same way every single time and because it is an explicit set of instructions, there must be no accidents in the creative process of creating generative art. But almost everyone I’ve talked to has said that their creative process for making generative art is loaded with accidents and surprises.

I wonder for your process, do you have something in your mind ahead of time, and then you go and code it and try to make what is in your head a reality? Or is it really more of an exploration where you’re continually surprised by what you’re producing? How does that work for you?

Stock 3 - 2020, Kjetil Golid

KG: I think I would say that both of these approaches are familiar to me. Sometimes I have a very clear idea, not necessarily on the finished visuals, but on the system that I want to create, and then later on, you can decide on the details, which are shapes and colors.

But a lot of times, I think of maybe a process or some sort of way of doing things, and I don’t really manage to imagine how it will look, and those are the most interesting cases, I think, where you actually have to program it in order to see what it will look like. The only downside there is that most of the time it will look quite boring and uninteresting, but sometimes it actually makes something really, really intriguing to me. And then it is easy to add on things, but then the next part there is to actually visualize this in the way that actually emphasizes these intriguing structures.

So back to what you asked with whether or not this is an accident. I think it’s partly that, because I don’t really know how it will look, but I never sit down and just let the accidents take control, because then it will usually not be very effective because you will only change things and you will kind of see what happens, and you won’t really progress much. To me, it’s important to have some sort of direction when you program, and maybe you make an accident yourself because of the randomness here, it turns out in a way you didn’t expect. But then I usually try to either understand how it turned out that way or just try to keep on my plan so that I don’t lose control in a way.

Dual - 2020, Kjetil Golid

JB: I think that makes sense, and it almost dovetails into one of the works that I wanted to talk about, one of your more recent works, dual, which features almost a battle between noise versus cellular automata. The theme of the Game of Life… show is loosely around cellular automata, and I know you have a work where there’s a structured cellular automata part to it and then noise, which I at least think of as randomness, and it almost seems as though there’s a tension between the two that sort reflects the process you just described. There’s some amount of control and some amount of almost chaos. Maybe talk a little bit about your inspiration for that piece or how you approached that piece.

KG: So, as you said, it’s cellular automata, so it’s a really small and strict set of rules which makes the basis of that piece. The noise part is actually part of another piece I made — not really a work, it’s more like a tool to distort any image, actually, that you bring. But the automata part is based on this traditional variant where pixels can be alive or dead and in a 2D grid. You scan each row, and based on some very small set of rules, you make each pixel white or black. I thought, what if you changed those, you don’t really change the rules, but you change the visualization. Instead of using black and white pixels, you can use lines that go in different directions based on the state above or the lines above. And then you use a similar set of rules to actually colorize the spaces between those lines. It turned into this quite nice hexagonal pattern. And the nice thing about this thing, in particular, is that you have total control over what it makes, so it may seem random, but it is actually based on some quite strict rules. The only seed for this randomness is the number you give it. So whenever you give it the number 120, every time you give it 120, you will get exactly the same output. But it seems so random because it turns so complex so fast.

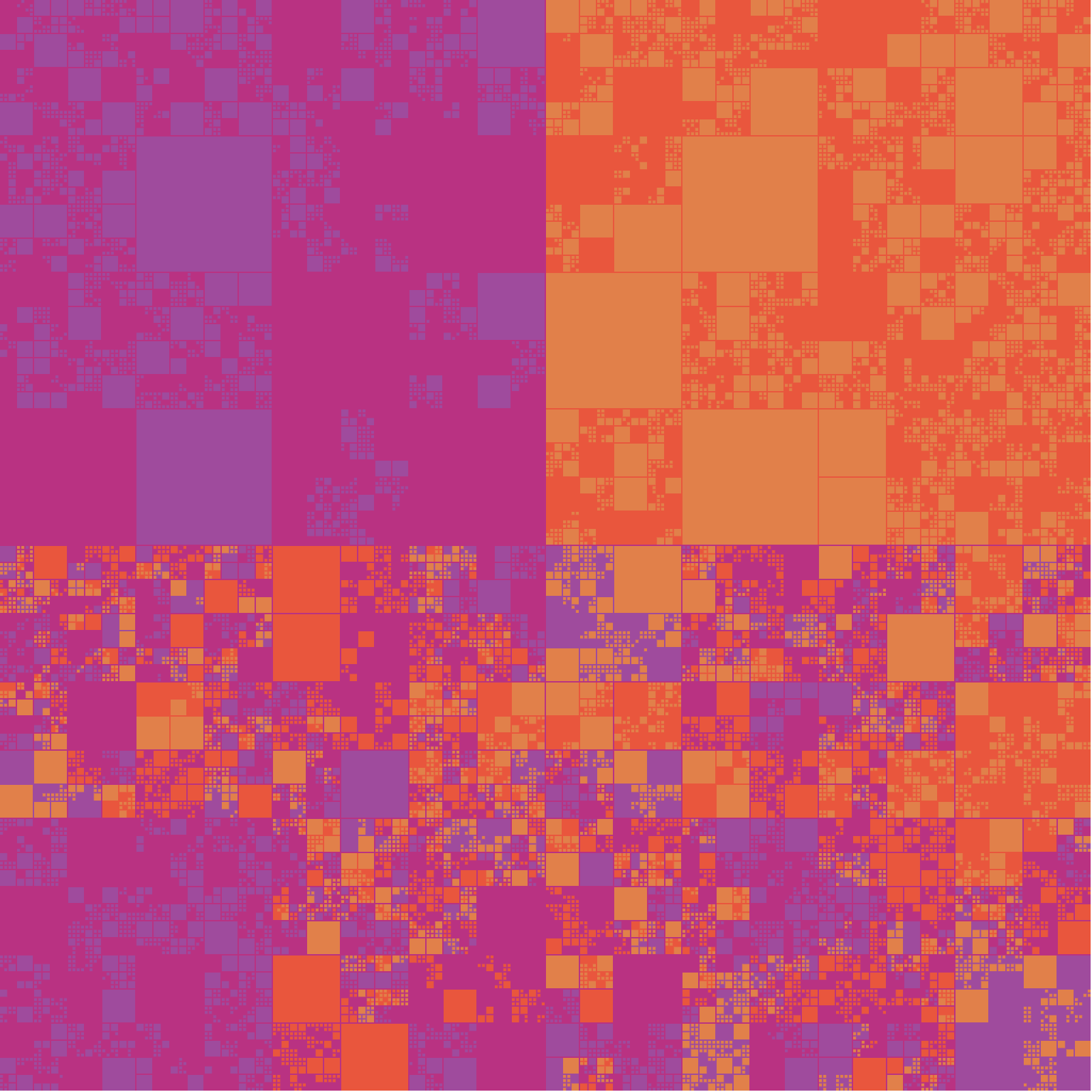

Rules - 2020, Kjetil Golid. [H200-V129–D33–A227], [H244–V60–D84–A121], [H61–V225–D209–A161], [H45–V147–D195–A228], [H247–V149–D176–A21] and [H15–V43–D30–A85]

JB: When I first was told about John Horton Conway and the Game of Life and cellular automata, those were new concepts for me in 2007, 2008. I was just starting to really learn about emergence in generative art and it was changing my world view. I think it’s easy to look at the complexity of the things all around us in the world and think, oh, wow, some higher power or something that we could never understand must have produced these things because of the level of detail and complexity they contain. But then once I realized that you can get such dynamic and complex output from such elegant and short input and code, it really shifted the way I think about things. I wonder how much your work been influenced by folks like Conway? Also, have they shaped the way you think about the complexity in the world beyond art?

KG: Yes. I think the first time I heard about Conway was through one of Stephen Hawking’s books, actually, where he made a similar point that you make here where he introduced the rules of the Game of Life and talked about how the only concepts you have in those rules are dead cells, live cells, and the concept of something they bring something else, and out of it, you get things like movement and spinners and gliders and generators, all kinds of things, which you can then start to talk about and make rules about. But in reality, that is not a concept at all from the maker. And similarly, he made the comparison to physics and laws we have about movement and gravity or electricity, but maybe there’s actually some even simpler rules behind that that we just haven’t explored, and then going further onto string theory and everything. But I really like that comparison. Maybe that was something that sparked my joy for these mathematical systems that lay the ground for these emergent structures, emergent systems.

Hatch Ruleset - 2020, Kjetil Golid

JB: Sometimes I think maybe I’m stretching it too far, but I think one of the really important things about generative art that maybe people don’t fully understand is that it is a shift away from the traditional mode artists work in. For thousands of years, we painted what we saw. We tried to mimic or give the illusion of the outside appearance of our world through portraits and landscapes and things like that, and I think one of the shifts that, to me, feels like something that we’re doing really for the first time in the last 50 years or so is that instead of just replicating the outward appearance of things, we’re actually trying to understand the systems that create them. And as artists, we’re creating our own systems that either emulate or simulate those algorithms or systems that we see around us. Does that make sense or hold water, this idea that artists may be moving towards building realities and making systems that can create rather than just trying to copy what they see that’s nature’s output of a system?

KG: I don’t know if it’s a conscious decision artists make, but I find it to be a nice thought that we moved from mimicking the visuals over to mimicking the logic in the processes. One of the things that I’ve played around a lot with is Lindenmayer systems, which have exactly that motivation, where Aristid Lindenmayer wanted to mimic the growth of plant cells and made this super simple and super beautiful Lindenmayer system, which is sort of a fractal, but which can make beautiful treelike structures and many other things, also, depending on how you visualize it afterward. I think that’s the beauty of a lot of these things — coming back to your question about what is the actual artwork here — and sometimes I think that it's this back end here, the generator, and sometimes it almost doesn’t matter how you present it because the structure behind it is so intricate itself, and it’s not about finding clever ways, you don’t need to be as clever to represent it visually because the clever part is already coded in there, so you just have to find a good way of representing it to just emphasize the structure.

Lindenmayer - 2017, Kjetil Golid. Visit his site to generate your own variations.

JB: There’s the emphasis of the structure, and in some cases, these are already algorithms that exist that artists like yourself are playing with or expanding in new directions. But I also wouldn’t undersell your abilities in what I would call traditional artistic skills — so composition, color, rhythm and things like that. I think about the 1980s — I’m fairly older, I guess — and in the ‘80s, a lot of the fractal work that was coming out were these sort of garish, ugly colors, and no real thought to composition. They were more like purely mathematical exercises, but there wasn’t a lot of sensitivity, for lack of a better word, or artistic training or background in it. But when I see your work, for example, to me, it feels like there’s a lot of thought into things like composition and color and balance. And those things go beyond just adding to the beauty of the system. I think they add sort of an emotive layer. We respond emotionally when we see colors or shapes or forms put together in certain ways. So I think you do have quite a significant role beyond just the system in making visual choices, which are also programmed. Do you know what I mean?

Fractal Squares - 2017, Kjetil Golid

KG: Yeah. You may be right there. There’s a lot of ugly fractals out there. [laughs]

JB: Right. Because a lot of people, I think, that maybe don’t understand this stuff think, well, one programmer’s program is just as artistic as another’s. I think that’s wrong on multiple levels. There are people that write beautiful code and people that write ugly code on the system side, and there are people that write code that can produce faithfully an algorithm, but it’s not necessarily aesthetically or emotionally engaging, and there are others who really have a skill and talent for that. And I’d kind of put you in the latter.

One of the things that I think is interesting, as we were talking about how some of these processes are sort of reflected in the natural world around us, is the recent conversation in the last two years around generative art and AI art, ML art, GANs (generative adversarial networks). More and more in the news, people are talking about, are these artificial intelligence going to replace artists, which I find kind of silly, but I guess some folks who I respect believe that it’s a real threat and there’s potential that things could go that way.

When I’ve seen GANs produce work on their own, and people try to promote it as art or sell it as art uncurated, I’m usually not very impressed. It just looks like a bunch of mush. Of course, in my opinion, there are some artists that are doing great work with AI and ML, but it’s usually the human intervention that makes it interesting.

Some of your tools are the closest thing I’ve seen to automating actually really interesting art. I’ve used some of your tools, and I drag a few different sliders and pick from different preset color schemes, and I’ve been very happy and pleased with the outputs to the point where I thought, ah, I should print this one out and hang it on my wall — and as an art collector, I’ve got limited wall space.

Image I generated using Kjetil’s Marching Squares (2019) algorithm tool

JB: There are a few questions packed up in there. What are your thoughts in terms of the potential threat of replacing artists versus maybe it’s just an augmentation of artists using some of these automation tools like AI and ML, or even traditional generative art or programming, in general, like yours? Should artists worry or think about the fact that what they do could be automated and replaced, or do you see these technological advances more as the opportunity to give artists a new tool? They’ll never replace the artists, they’re just a new tool that can extend their creativity?

KG: Right. I certainly don’t see this as a threat in any way. I guess in the most extreme case we would end up at a place where — maybe we're already there —where we can’t really distinguish AI art from human art. In that case, I still don’t see this as a bad outcome, because then we’ll just have more artists, and it wouldn’t stop humans from making art. And I also think, well, if computers make better art than us, then I think we have a bigger problem than a computer making art.

But I think what might be more interesting to see is what you talk about, this collaboration thing where we traditionally had the direction of someone having some sort of intention that they wanted to express or some meaning that they express through their art, and then people soak that in. But now we are in a state where computers make art devoid of any meaning, devoid of any tension, but maybe we are the ones that can implant it with intentions. So, for instance, you see in GANs, artists have started generating music and generating lyrics for their music, and even though that may be a bit gimmicky or something, it’s still a nice thought that, yes, they make lyrics that are void of any meaning, but it’s easy for us, we are really good at that, to actually implant this with meaning afterward. So I think that’s kind of an interesting idea, to turn that intention to expression and turn that around so that you only have computers making a lot of expressions, and then we are giving it meaning afterward.

JB: That’s a fascinating insight. It makes a lot of sense that the production of images is one thing, but the making of meaning is another, and it feels, at least to me right now, that making of meaning — whether it’s the artist, the curator, the art appreciator, or some new role that evolves — it’s the humans, at least for now, that really excel at making the meaning.

KG: And I never said that my art has had a lot of meaning. I’ve been quite open that it’s only experimentation for me to visualize structure and systems and intriguing visuals. So I am fully open [to] that kind of art where you have a completely computer-generated thing, as long as that is not the interesting part. I don’t want my art to be interesting because it’s made with a computer or because it’s made automatically. Usually, people don’t care about looking at mediocre art or listen to mediocre music just because it was made in some unconventional way.

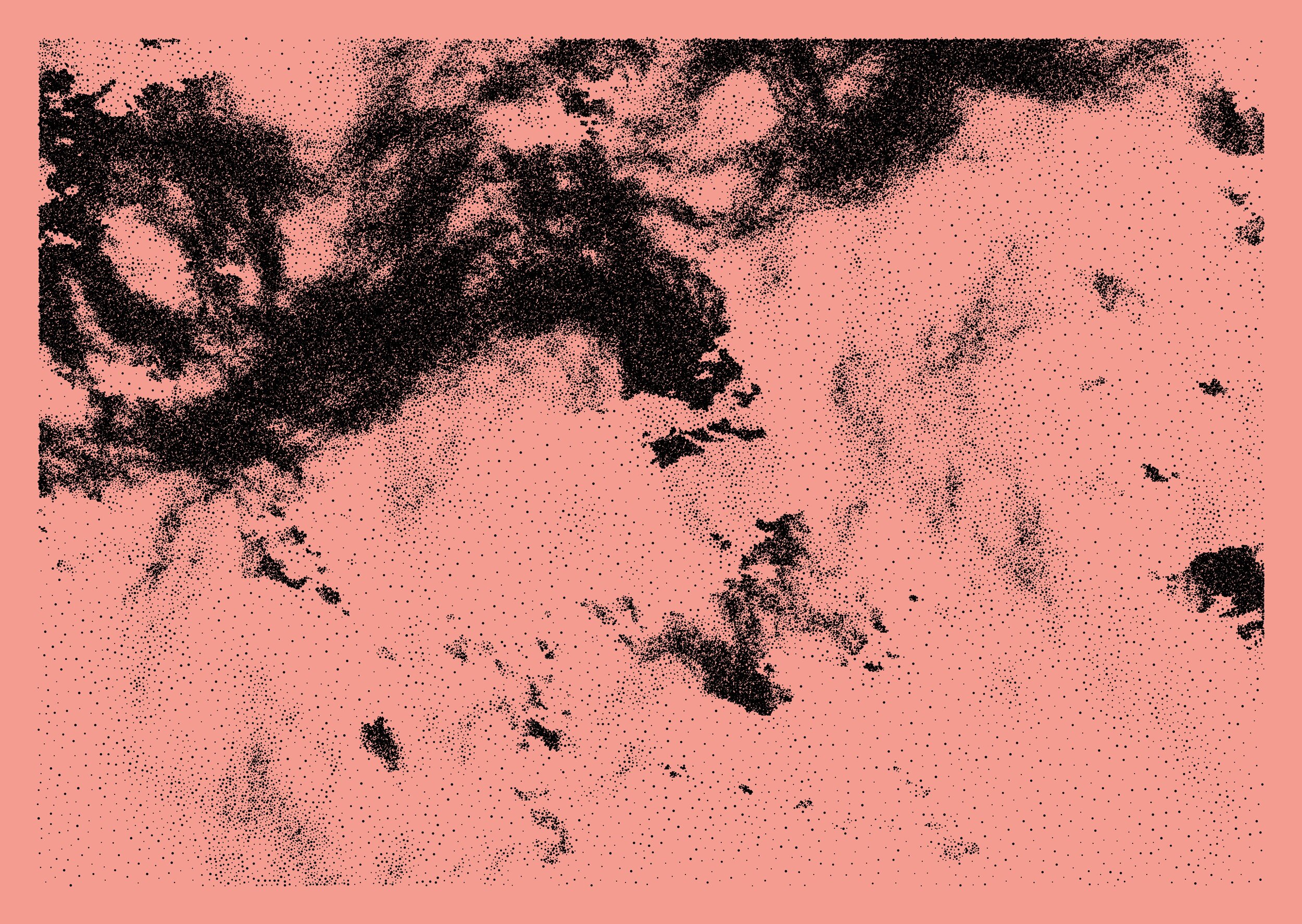

Ash Dragon - 2020, Kjetil Golid

JB: How do you want people to look at your work? What experience or what do you want people to take away from your work? How do you want them to benefit from it? Or do you think more about, this is just something you enjoy and share it without so much of a concern about how people receive it?

KG: It simply started that way, that I made this mostly for myself, and I know I made something cool when I played with it for hours, just tweaking variables and different perimeters. Usually, when I find it funny and I find it intriguing to look at, a lot of other people experience it in the same way. I haven’t really thought about it a lot more than that. I have not started making art for my crowd. I usually make new things when I have either read about some new process or some new algorithm that I haven’t heard about before.

JB: My experience, for what it’s worth, is that artists that make work for themselves are the ones that most successfully engage other people. Maybe it’s a little bit Zen, but the harder you try to please a crowd or make something that you think people will like, the less honest or sincere it can feel sometimes. I think part of what we’re addicted to as art appreciators is getting a window into someone’s sincere exploration into a new direction. So, for what it’s worth, I would encourage you to continue to work in the same direction.

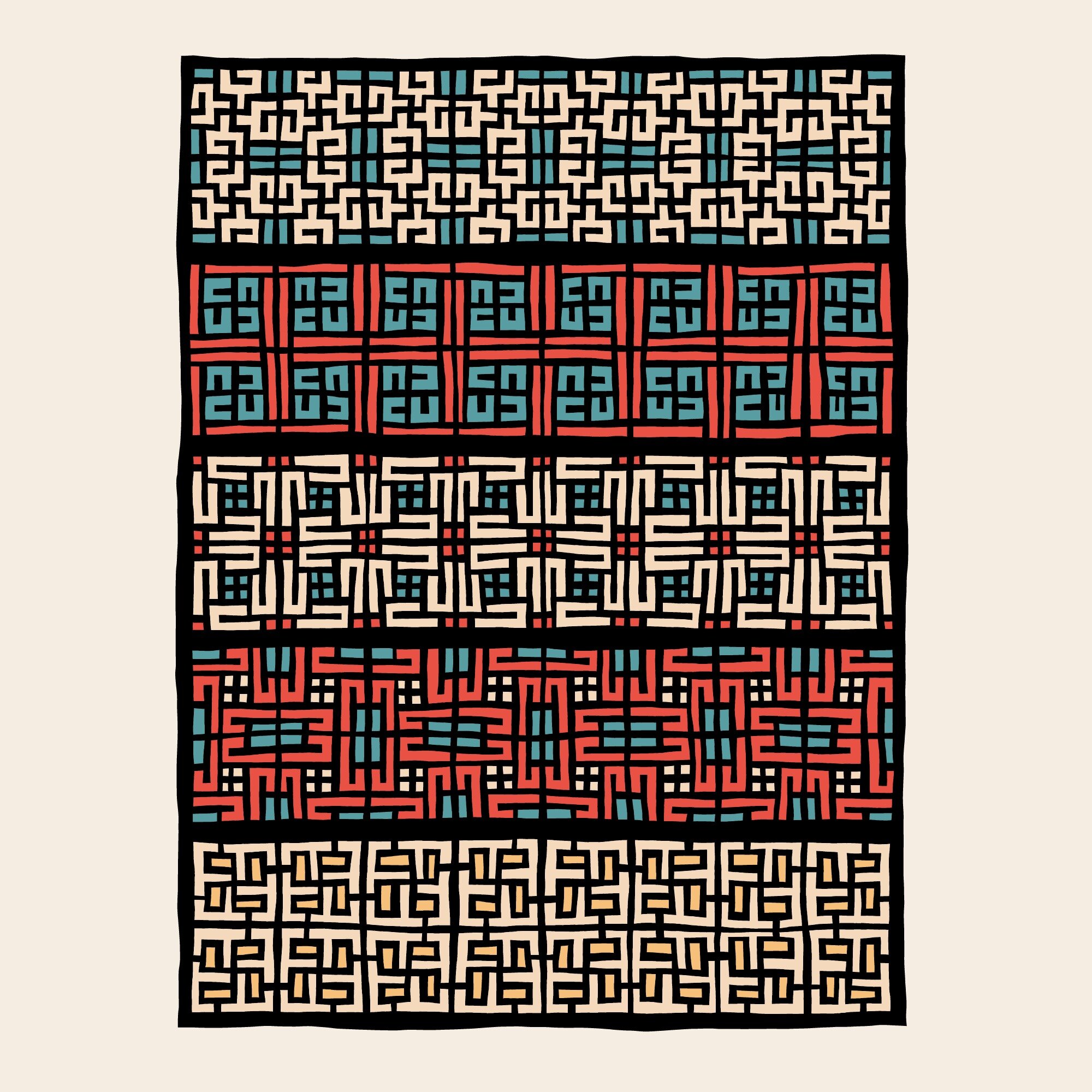

Generative patterns - 2020, Kjetil Golid

JB: All of your work has some really interesting color palettes that I associate with you — and I’m pretty sure you’ve done some work with sort of auto-generating color palettes. It’d be nice to know a little bit more about that. But then some of my favorite work of yours might be the curve-scapes, the curved landscapes, which I think have no color at all. Maybe if you could talk a little bit about some of the work you’ve done with the auto-generating the color palettes, and I might bug you to talk a bit about the curve-scapes after that.

KG: Most of my earlier work has been mostly monochromatic because I didn’t feel like I needed color. So, for instance, when I talk about with the Linenmayer systems, you can grow beautiful, random trees. I felt there that the colors only added noise because the structure was there, so clear. But then later on, I think maybe it was cellular automata, one piece where I started seriously introducing some color palettes, and I found that it’s really added to that work. And after that, I don’t try to push these palettes into all my work. But when I feel like it actually pushes the work further and it makes the structure clearer, I experiment with some color. The palettes are not auto-generated, most of them, but they are kind of curated by me. I spend a lot of my time just roaming the Internet for nice photography, illustrations, videos and everything, and whenever I see a nice frame with some good colors, I try to extract the palette from it. And I’ve collected this into my library that I call “chromatome”. First it was just a personal tool just to simplify the use of colors in my work, but then later I just open-sourced it so that more people can use it. It starts becoming quite a large collection of color palettes. It’s almost hard to handle the amount of palettes.

Generative patterns - 2020, Kjetil Golid

JB: I find them phenomenal. And knowing that you curated them by hand is even more impressive. I think when I see a work that has one of your palettes, the color is one of the first things that hits me or helps me understand that I’m looking at one of your works. And then in using your tools, you turn rapid application of color palettes into a tool where you can try out different things. And it’s amazing how much quickly going through different sets of color palettes dramatically changes the feel and response to the images.

KG: Yes. It’s also fascinating to me how one color palette works so well in one piece and it totally misses in another piece. So there’s a lot of theory behind there which I haven’t really delved into, but I would really like to explore further, how the connection between shapes and rules you have are different shapes and how the collection of colors can emphasize that.

JB: I can imagine you could spend an entire lifetime delving just into that. You think about color theorists like Johannes Itten or Josef Albers, or Munsell is another one. You know, Albers with just his squares, he just created nested squares over and over and over again. People thought, well, that’s boring, but he was trying to hold something constant so that he could drill closer in on the variability of color and impact on us. I really enjoy that aspect of your work.

Who are some other artists that you look to for inspiration? It doesn’t have to be generative artists, although that would be interesting, too. Are you an art lover, art appreciator, or do you pull your influence from nature and other sources?

KG: Outside of generative art, I don’t have a lot of knowledge about traditional art or any other kind of digital art, really. I have, as a natural consequence of this, seen a lot of generative artists in the last couple of years. I really love people like Tyler Hobbs and Matt DesLauriers, for instance, are the two big ones for me, and also Manolo from Argentina, who I really like, putting out such a great volume of amazing generative content all the time. It’s just mind-boggling to me.

JB: Yeah, I didn’t think Manolo was a real human until I interviewed him. [laughs]

KG: [laughs]

JB: I didn’t understand how anyone could produce that much work and reinvent themselves every single day that way. But he is a real person. He is a very sweet and nice person.

And yeah, I like Matt’s work a lot, as well. I don’t think I know Tyler Hobbs’ work as well, so I’ll have to check that out. But I know Matt also does a lot with sharing his code and teaching. There are many reasons to love generative art, but one of them when I started in 2002, 2003 was just how generous and open the community is with sharing code and helping each other learn, and I think that makes it really unique and fun. It’s sort of the opposite of the art world which is super competitive and can be kind of petty sometimes. Hopefully that spirit stays.

So two questions. For the average person these days, should some level of programming literacy be mandatory as part of a common core education that people have, or it doesn’t really matter and leave it to the engineers? Second, do you think people need to have some level of understanding of code to truly appreciate your work?

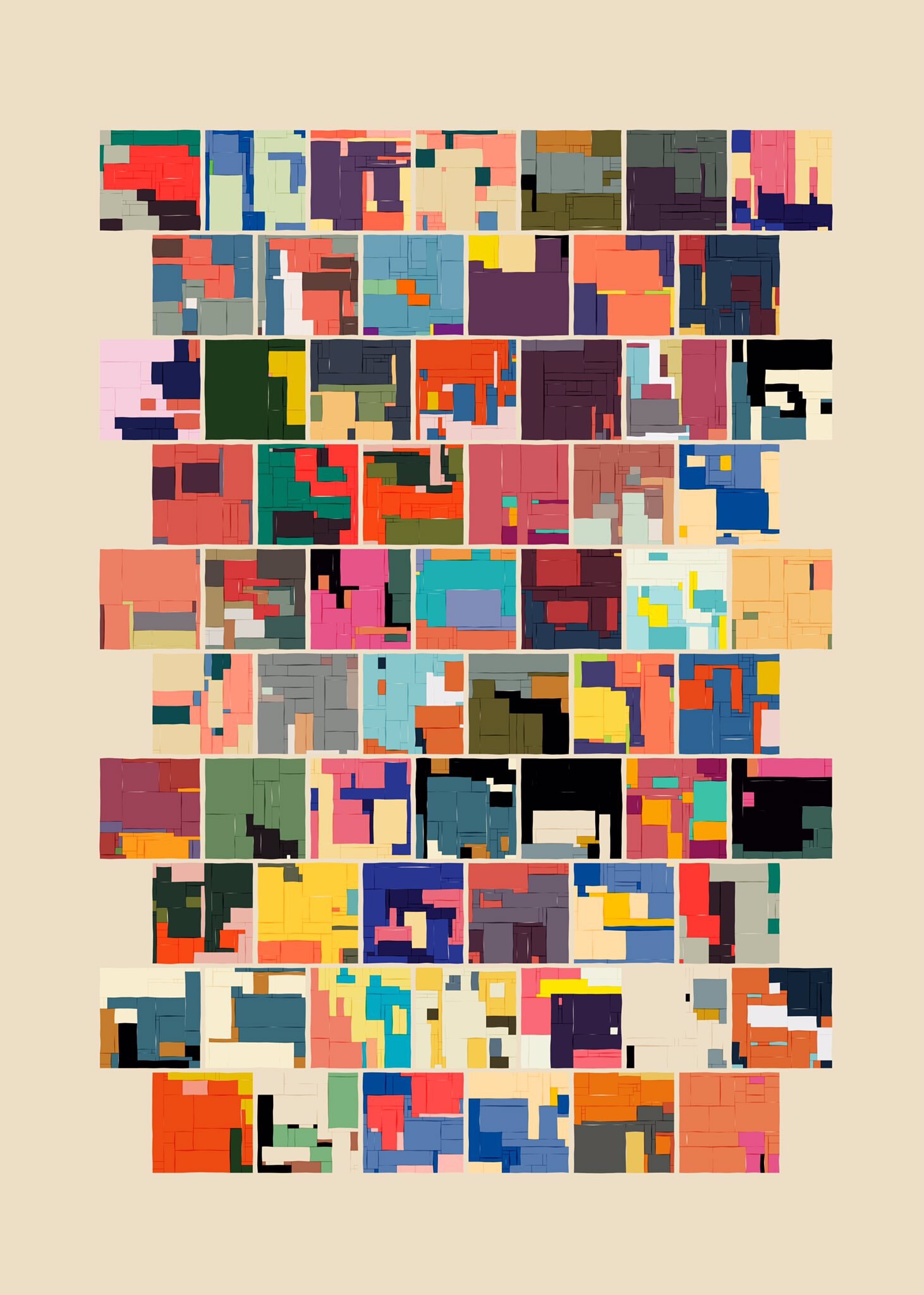

Studio apartments - 2019, Kjetil Golid

KG: I don’t think that all people should learn programming, but I think more and more jobs would be centered around some sort of programming. So I definitely think that it should be introduced earlier than it is today, but as sort of general knowledge, I don’t think it’s necessary to bring that pain upon themselves. [laughs]

JB: [laughs] Yeah, learning to program can be painful for sure. For me, it was either recursion or — I think it was actually pointers. Before that, I was cruising along and was like, I could be an engineer, I understand this. And then I got to pointers and I was like, okay, this is my wall. I’m done. [laughs]

KG: [laughs] Right. I don’t think people should need to have any sort of programming background to appreciate my work. At least, I hope I have some followers don’t know programming. I don’t know. But as I said earlier, I hope people don’t find this interesting because it’s computer made or because there’s code behind it. Of course, it’s very nice when people say they find the code also interesting and used it for several things. But I hope it’s not necessary. I hope it stands as a visually intriguing work on its own, and if people think that I made it by hand or in Photoshop, that’s totally fine by me.

JB: That’s fascinating. Such a wide spectrum from people that think, well, the output doesn’t matter at all, it’s my code that I built that matters, to — I think you’re a bit more on the other side of the spectrum where it’s almost as if they focus too much on the tool, then it’s almost like the novelty of the tool takes away from the output, which is what, in this case, maybe matters the most.

KG: I am very open to people asking me how I made things, and I think it’s nice to see that people are curious about the process. I’m also very open about the process. But I think it’s a bit weird sometimes, that you probably wouldn’t — the first thing you wanted to ask a painter about would probably not be what kind of paint he uses. But somehow a lot of people find the process very interesting whenever it’s computer-generated. Maybe it’s because for some people, more approachable; for some people, definitely not more approachable. But I guess the people that actually are more interested in this have some sort of background in computer science or something similar.

JB: I really appreciate your time, and I love your work and I'm glad we had the opportunity to dive into it a bit deeper.

I like at the end of an interview, I like to make sure that I ask if there’s anything you’d like to share that I haven’t touched on, any new work that you’re building that you think people should know about, anybody whose work you think we should check out, anything that we didn’t cover that you think we should go over?

KG: If you haven’t checked out Tyler Hobbs, check him out.

JB: Will Do! Thanks again for your time!

![Rules - 2020, Kjetil Golid. [H200-V129–D33–A227], [H244–V60–D84–A121], [H61–V225–D209–A161], [H45–V147–D195–A228], [H247–V149–D176–A21] and [H15–V43–D30–A85]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59413d96e6f2e1c6837c7ecd/1602429935549-WQWP9WE223TEDQ9N4BDW/1_lmYIHgSXq-59A71ogmcdKw.png)