We studied the historical data on works of NFT Art across the SuperRare marketplace*. This is what we found.

*Data as of end of March 2021

Futuristic, retro and sci-fi themes are frequently explored and highly coveted by collectors

“3d” art is the most viewed with higher selling points, perhaps reflecting a ‘medium’ specific to crypto art

In general, number of views highly correlates with price: the hype machine is real

As in the traditional art world, NFTs tagged with “drawing” tend to sell for less

The average color palette of NFTs tends toward purple, reinforcing an aesthetics rooted in technostalgia

We have sought to identify, based on available data, what NFTs (non-fungible tokens) are actually contributing to visual culture beyond simply fuel for financial speculation and environmental extraction. Our premise has been that it stands to benefit crypto artists to be aware of their community’s aesthetic and thematic priorities. However, the data may also be of interest to traditional fine artists, who may be looking to migrate to an artistic arena less dependent on intermediaries than the contemporary art scene, and who might bring with them certain conceptual tools which could prove valuable to crypto art’s long-term future.

Point of Information

This text considers the terms ‘crypto art’ and ‘NFT Art’ to be interchangeable. However, clearly not all digital (nor indeed physical) artifacts tied to NFTs constitute NFT Art. Given the increasing tokenization of collectibles, there is already some agreement that NFT Art stands apart and that its value depends on more than mere scarcity, in much the same way that traditional fine art was separated from decorative arts for centuries. Whether such segregation is appropriate in this instance, however, is highly contentious, given the democratic principle by which, in theory (and on Rarible), any digital artist can tokenize their creativity as an NFT. To then introduce a separate field of NFT Art into which only some works qualify automatically implies hierarchy and structural unfairness.

We use the term ‘crypto art’ therefore to alleviate this problem by accepting the possibility that all creative works issued with NFTs might be considered NFT Art. It is also to remove the sense that the primary object of interest in NFT Art is the NFT itself, rather than the creative process. At the same time, ‘crypto art’ is broad enough to encompass a variety of approaches, such as Plantoids, that seek to explore the blockchain as a wider ecosystem. It therefore accepts that, while an aesthetics of crypto art should prove useful, its associated privileging of artistic originality is no longer adequate when evaluating art today.

In practice, the storage limitations of the blockchain dictate whether or not the work itself is stored “on chain”, as in the case of Autoglyphs, or “off chain”, as with CryptoPunks. We question whether such collectibles, despite being marketed separately from the vast majority of NFT Art, aren’t in fact its purest incarnation. This text therefore seeks to disentangle the making of art from the manufacture of markets.

A new conversation

One motivation for this study is that the issue of aesthetics has so far been overlooked in the mainstream commentary about NFTs. Given the market’s exponential growth, as well as the urgency of debate surrounding crypto art’s environmental cost, this is perhaps unsurprising. However, it offers an opportunity to ground the question of aesthetics in data, rather than the kind of lofty rhetoric often used to drive up prices artificially. We have sought to start a conversation about aesthetics in a way which acknowledges the concept’s historical freight, while prompting us toward greater awareness of the creative toil behind crypto art. That one of the hallmarks of NFTs so far has been a kind of beguiling slickness may be one reason why the craft has gone largely unmentioned up till now. When that craft also reflects a multitude of digital approaches it makes the question of aesthetics even more problematic, if no less intriguing. Ultimately, what is at stake in the debate over aesthetics is not simply the question of “what makes good crypto art?” But “what is crypto art?” Since without a frame of reference on which all parties agree, those who control the market will invariably determine what constitutes crypto art itself, and therefore who gets excluded.

The search for an aesthetics of crypto art therefore requires investigating the standards by which crypto artists, as well as collectors, currently distinguish works of NFT Art as more than simply digital artifacts that have been tokenized. This is important because it acknowledges the existence of different skillsets and levels of technical facility among the community of crypto artists, whose talents have been honed well away from traditional art institutions. It’s also something artists themselves are clamoring for, as a way of rebalancing the debate away from a fetish for the token itself.

About the data

Supported by Artnome, Flash Art and MoCDA (The Museum of Contemporary Digital Art) our team has examined a wealth of data relating specifically to the SuperRare market. We chose SuperRare for its overall market share as well as its role in popularizing the collection of crypto art. Of course, a market is more than the sum of its artists and collectors, indeed SuperRare’s selectivity when assessing artist applicants reinforces the continuing role of gatekeepers in defining the bounds of artistic legitimacy. We therefore have to accept a sample that is biased according to SuperRare’s curation, and also constricted by the current artwork formats supported.

At 22,018 works, however, the sample is significant enough to allow us to establish the priorities of the key parties. While the relative youth of the marketplace as a whole means that its founding community of artists, collectors and owners remains invested in securing a stable level of quality, or ‘Rarity’, in the art circulated therein. The fact that all of SuperRare’s NFTs are issued as single editions, in contrast to other marketplaces, also highlights its privileging of aesthetics over mass production – quality over quantity. In the long term, however, this attempt to enshrine SuperRare as a guarantor of quality will depend on mutual agreement about what constitutes quality in the first place. Based on the data, there is already some evidence as to how one might define in words such a nebulous concept.

What artists are tagging

We considered the role of tags in clarifying artists’ labelling of their work according to common, as well as outlying, categories. Given that the market for NFTs is now a nexus for multidisciplinary artists from across the spectrum of digital creativity, there is a strong case that any aesthetics must build upon grassroots foundations. We have therefore tracked the relationship between artists’ tags and the price their works have sold for. In this way, our aesthetics articulates the motives of artists themselves, whilst acknowledging the qualities valued by collectors.

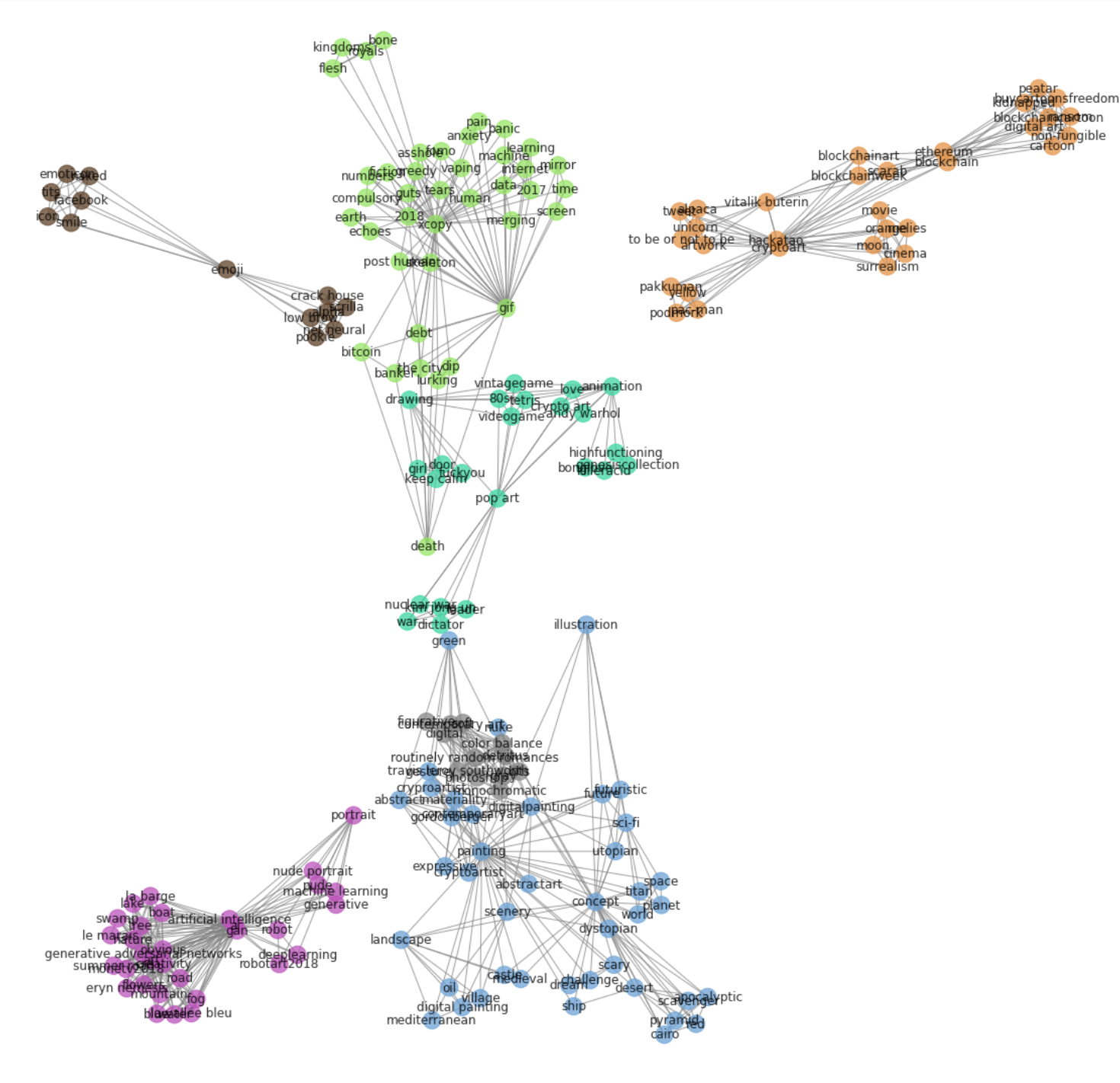

The SuperRare Tag Network: A visual representation of 344,050 artist-selected tag combinations

The data visualized in the above network accounts for every artist-selected tag minted on SuperRare. It reveals the uniqueness of certain tag combinations: for instance, Robbie Barrat’s tagging of #MachineLearning together with #Artificialintelligence for his AI Generated Nude Portrait #2 (2018). It also shows the overall complexity of relationships between tags. In total, there are 17,887 unique tags, as well as 344,050 unique combinations of tags, which suggests that artists tend to select them in a manner that distinguishes their work. This emerges more clearly when one segments the network, as in the below sample of 1,000 tag combinations.

A segmented network of the first 1,000 artist-selected tag combinations

Some tags appear with very high frequency. The most commonly selected by artists is “3d”, tagged with a little over 17% of all SuperRare NFTs. Also in the top 5 by number of NFTs are “abstract”, “animation”, “gif”, and “surreal”, each selected with at least 10% of SuperRare NFTs. We focused on the top 50 tags by number of NFTs and the average selling price for works with these tags.

Top 50 Tags by Number of NFTs: Average Price ($) vs. % of all SuperRare NFTs with that Tag

At $7,394 (ETH equivalent at sale), “sci-fi” is the highest grossing tag by average sale price, often combined with “space”, another top 50 tag with a high average price ($5,730). “2d” and “surreal” are the second most expensive tags among the top 50, just shy of $6,000, a fact which reveals the equivalent value to artists of both aesthetics and thematics. “Nude” is the highest-value tag of fine art’s canonical subjects at $4,903, though “portrait” remains more popular. These values may have been driven by Robbie Barrat’s early dominance on the SuperRare platform, though they suggest the male gaze is still very much alive.

Unsurprisingly, tags related to blockchain and cryptocurrency rank among the top 50, including “bitcoin”, “blockchain”, “ethereum” and “eth”. Given the historical bond between NFTs and Ethereum, rooted in the ERC-721 standard, one might expect a predominance of Ethereum lore in crypto art. Yet, Bitcoin is just as infused into SuperRare mythology.

Ethereum vs. Bitcoin: Network of SuperRare tag combinations containing “bitcoin” or “ethereum”

The network above explores the relationship between NFTs tagged with “bitcoin” and/or “ethereum”. The purple dots to the left represent tags paired exclusively with “ethereum” but not “bitcoin”, while on the right in orange are tags paired with “bitcoin” but not “ethereum”. Tags with both are in green in the middle. In the Ethereum-only region, we find some tags common to the Ethereum narrative – such as decentralized apps (“dapps”) and the “0x” ETH address prefix. Tags paired only with Bitcoin include myriad references to the Bitcoin genesis story and Satoshi Nakamoto. Common to both are themes circulating in the crypto community at large such as “hodl”, “lambo”, “fiat”, and “blockchain”. While tags referring to Ethereum co-founder and de facto leader Vitalik Buterin are paired with both Bitcoin and Ethereum – perhaps indicative of a rejection of Bitcoin maximalism. Overall, NFTs with either “bitcoin” or “ethereum” tags fetched lower prices on average ($1,814 and $1,263 respectively) suggesting that these topics are now somewhat clichéd for the SuperRare community.

The “average” SuperRare NFT generated by blending 22,018 works together

Five of the top 50 tags are concerned with color, though specific colors are limited to “red” and “black”, with red selling for slightly more. Seeking to probe the palette further, we mixed the colors of the entire SuperRare universe together to produce the above representation. Dominated by pastel hues of red, pink and purple, the outcome is straight from the Rothko school of data visualization. Suggestive of libidinal melancholy, the ultimate palette has an unmistakable allure of technostalgia that fits the defining themes of the market. Coupled with the popularity of “abstract”, “psychedelic” and “surrealism” – the movement that imagined a melting world – it is an irony of this attempt at an aesthetics that we have ended up with an iconography of Web3.

On the other hand, the stress on production process evident in the frequency of “2d” and especially “3d” – which is incorporated into 89 tags across the marketplace, from “3danimation” to “3dillustration” to “3drender” – signposts the new media most suited to crypto art. A sample of the 50 most popular tags also supports the impression of a break with tradition. 30 bear no relation to traditional fine art terminology, though five of the top ten do. This reminds us that, as a media ecology, the blockchain deserves media terminology, but as a discourse crypto art remains a hybrid of analog and digital media.

Some media critics choose to adopt the Classical Greek term technē (‘craft’), rather than aesthetics, when considering the set of principles by which media texts are crafted today. In reality, aesthetics only became the defining aspect of art in the Enlightenment, prior to which issues of ‘technical’ quality and ritual function had predominated. While it arguably hasn’t been the priority of fine art since Duchamp repurposed the urinal from a bathroom wall to the floor of a New York exhibition space. This gesture marked the birth of conceptual art as an avant-garde strategy, beginning the process of divorcing art from aesthetics that continued for much of the twentieth century.

Crypto art proposes a finite end to the requirement that art be physical at all, thereby extending the lineage of attempts to dematerialize the art object. While NFTs depend as much on the energetic process of minting, as well as the economic logic of the ‘drop’ (often occurring simultaneously) as they do on the aesthetic appearance of the digital artifact. Today, aesthetics is only one part of a composite whole whereby media + token = crypto art. Nevertheless, aesthetic appraisal remains a crucial means by which collectors differentiate one NFT from another, beyond considerations of price, hype, etc. One thing that crypto art shares with the so-called ‘legacy’ art market is that NFTs tagged with “drawing” tend to sell for less (averaging $2,216). In reality, despite their implication of a lack of finish, these ‘drawings’ are often highly polished. They therefore reveal a potential misalignment between tags and their perceived value, one that reflects an unfortunate hangover from crypto art’s prehistory.

What collectors are watching

Our analysis of collector views and favorites has allowed us to better quantify the priorities of each party to the market. SuperRare only counts views from its pool of 2,000 active collectors, meaning the data ignores those simply passing through. The fact that a significant proportion of crypto art’s early collectors are also artists adds to the impression of a shared set of principles underlying the market.

Focusing on the top 50 tags once again, we find a high correlation between the average price and the average number of views by tag. It is of course hard to untangle this relationship but it may run one of two ways: the most popular NFTs are considered of higher quality and therefore demand higher prices or the NFTs that have traded for the highest prices attract viewers more interested in the outcome of transactions.

Works with over 500 views are dominated by name-related tags, which implies that the hype surrounding individual artists, as well as their time on the platform, is responsible for escalating prices. The most viewed artists are Hackatao, XCOPY, Pak, Coldie, and Robbie Barrat, who together account for 116,544 total views or 7.7% of all views on SuperRare despite only producing 3.8% of SuperRare’s NFTs.

Users on SuperRare can also choose to “favorite” NFTs. Given that the option to favorite a work necessitates viewing it, a correlation between views and favorites is inevitable. However, there are some outlier works. ZOMAX’s 6088AD (2021) counts 109 favorites from only 1,224 views, which hints at the outsize influence of social media in driving demand. By contrast, Vitaly Bulgarov’s THE LAST TOKEN (2021) – a reinterpretation of Leonardo’s Last Supper (1495-98) – has 2,469 views but only 55 favorites.

ZOMAX, 6088AD, 2021

Vitaly Bulgarov, THE LAST TOKEN, 2021

Only 14 NFTs on SuperRare had more than 1,000 views by the time of publication, the majority of which demand the highest selling points. It may be that these are the works deemed “good” crypto art by the SuperRare community. Yet FEWOCiOUS is also highly viewed despite producing works less seamless than the majority, evoking something akin to a Hoch-Guston hybrid. At only 18 years old, FEWOCiOUS offers an insight into a world unencumbered by training. On the other hand, his use of endlessly looping animations that stall the spectator between morbid curiosity and hollow consumption remains the essence of the NFT experience.

FEWOCiOUS, The Sailor, 2021

The problem of aesthetics

One characteristic of fine art over the last fifty years has been the proliferation of hybrid installations rather than discrete works of traditional media: painting, sculpture, etc. In practice, while this development exorcised old hegemonic actors, it gave over the measurement of quality to the keepers of the gallery system. This invariably created a dependence on hype – couched in the language of meaningless artspeak – to fill the void. That it coincided with the growth of floating exchange rates, especially the US dollar from the early 1970s, should come as no surprise. Contemporary art today is as much a function of financialized capitalism as any other marketplace. What crypto art stands to offer is a notion of quality that is potentially more secure than contemporary art because it is more coherent in its media.

While therefore useful, aesthetics remains highly problematic, premised as it is on the ‘disinterested’ viewpoint of a supposedly neutral agent who is, in reality, the very definition of an elitist white male spectator. Crypto art’s detractors might therefore argue that this kind of ‘aesthetics’ is no more than NFTs deserve. Certainly, it would take a monumental act of sophistry to claim for crypto art the same kind of ‘autonomy’ from mass culture that Theodor Adorno once tried to claim for art. If anything, crypto art is the most rarefied (or at least the most recent) product of the cultural industries, represented by exactly the community of multidisciplinary artists historically excluded from the art world. Its problem is how to reconcile further environmental damage with the potential of NFTs to redeem a generation of digital creatives from lives of economic precarity.

What the pandemic achieved was a total flattening of all forms of artistic display, and importantly sale, across online platforms. On the one hand, this merging of apparently discrete image economies revealed the lie of contemporary art’s separateness from wider culture. On the other, it catalysed the growth of NFT marketplaces in which a new wave of ‘elite’ images could leverage the blockchain for verifiable digital scarcity. With the playing field levelled at last, it remains to be seen how the relationship between different art markets as well as their accompanying discourses plays out. Our aim has been to point a way beyond the present situation, in which speculation appears to be as much a driver of art’s value as the works themselves.

In our view, it is time to untether crypto art from the logic of the derivative that has so fuelled contemporary art in recent years, and replace it with a new arsenal of critical strategies. Perhaps with this in mind, Kanon is currently collaborating with SuperRare on a project that uses smart contracts to reimagine artists’ resale rights in the spirit of Seth Siegelaub and Robert Projansky’s original vision. Whether crypto art is ultimately defined by its nuance as a financial instrument rather than the aesthetics of a digital artifact remains to be determined. What is clear is that these two components exist in a dialectical tension which threatens to further tighten the deadly embrace between art and money.

In his book Digital Aesthetics (1998), Sean Cubitt identified the drift of aesthetics away from ethics toward the neoliberal imperatives of transnational finance capital. For him, ‘the social production of the future as a field of possibility is the enterprise of digital aesthetics.’ We contend that it is exactly at the moment of art and money’s closest proximity that new forms of social practice might be forged. As crypto art increasingly cross-fertilizes with the critical strategies of contemporary art it has the chance to become a site for the critique of crypto-colonialism. Likewise, it will be in the contribution of new media artists, game engine designers and their kin that a new aesthetics will shape a new ethics of art’s production.

Highest Sold “scifi” NFT at 130.0Ξ ($251,916): Mr. Misang, #09. Company entrance, 2021

One noticeable trait of the crypto art released so far is its tendency to cross-breed traditional genres and retro styles with the hype machine surrounding digital trends. Whether the resulting chimaeras offer a pathway forward or simply a perpetual return to commodity fetish is as yet unclear. What is evident is the distinction between artists who use SuperRare to repackage works in NFT form and those whose work is purposely designed – indeed could only work – as an NFT. Mr. Misang’s recently released #09. Company entrance (see above) captures this tension perfectly as an animated version of a work from an earlier series of illustrations, titled ‘Modern Life is Rubbish.’

Isolating the specific qualities of NFT Art, its ‘medium-specificity’ to take a modernist trope, can be instructive in establishing its long-term trajectory as an art form, beyond simply a novel asset class. Of course, it may be that crypto art’s very multiplicity comes to define it in much the same way as art after modernism. However, it is hard not to see such a situation simply producing new forms of pastiche, rather than the kind of vital dissonance that decentralization potentially affords. Endless variety should not be confused with cultural vitality; it merely entrenches a state of neoliberal numbness in which aesthetics and ethics remain permanently uncoupled. One of crypto art’s most important achievements so far has been to puncture the illusion of contemporary art as a space of ‘high’ culture. It must not fall victim to the same hubris.

Alex Estorick is Contributing Editor for Art and Technology at Flash Art. He founded the magazine’s digital column, “The Uncanny Valley”, specializing in the relationship between AI and contemporary art.

Kyle Waters is a data scientist working at the intersection of art, tech, and machine learning. He has been contributing to Artnome since 2018. His recent work focuses on the social dimension of NFT collecting.

Chloe Diamond is a writer and curator specializing in blockchain, data and art. At the Museum of Contemporary Digital Art (MoCDA) she works to document and advance the position of digital art through curatorial insight and education.