In 1936, in the middle of the Great Depression, a young Walt Disney turned down a deal with United Artists because they wanted to own the rights to his cartoons in a new medium that few had even heard of… television. “I don’t know what television is, and I am not going to sign away anything I don’t know about,” Disney reportedly said at the time. It was a bold decision during uncertain economic times that showed great foresight on Disney’s part. By 1966, it was estimated that an astronomical 100 million people were tuning in to watch Disney television shows.

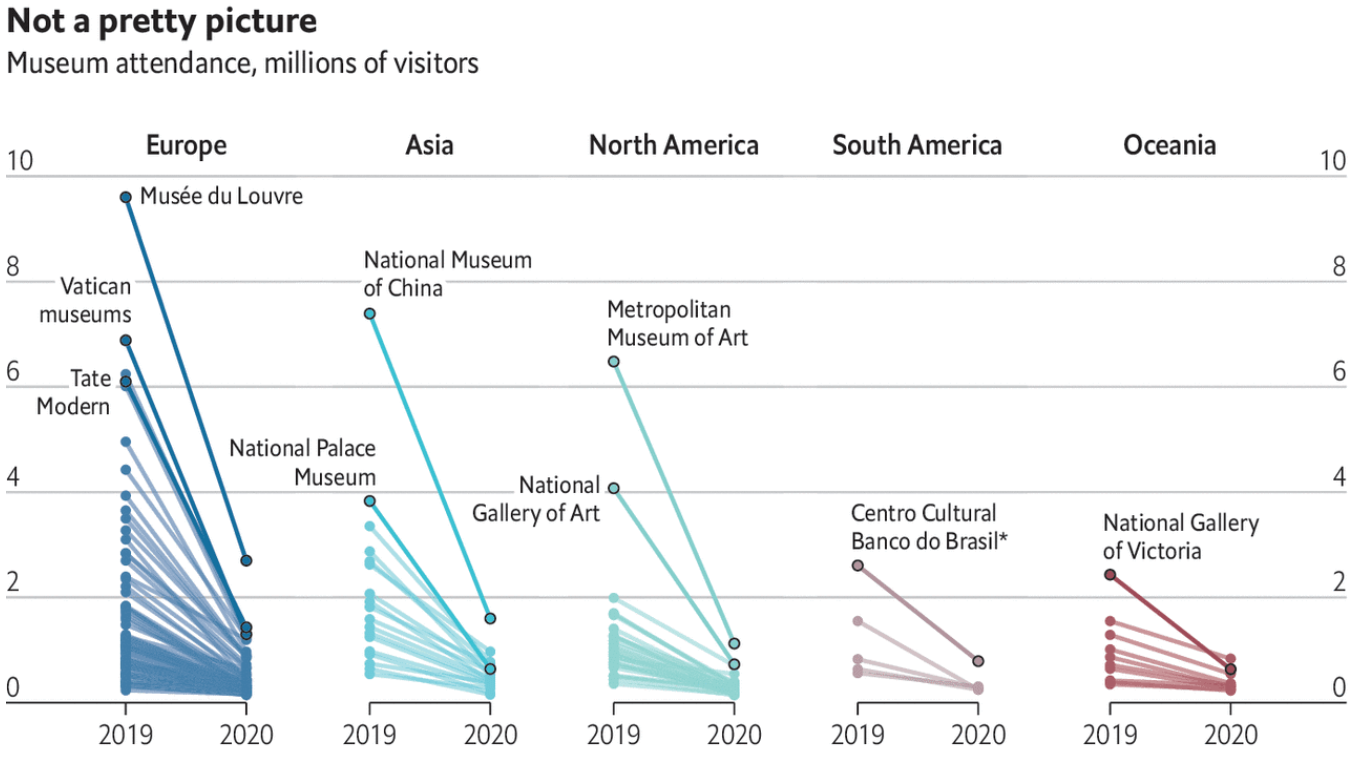

Coming out of a COVID-19 shutdown, many museums have found themselves in their own financial depression trying to recover from a prolonged absence of ticket sales. And with news stories of Christie’s selling an NFT for $69M and the NBA making hundreds of millions in NFT sales, it makes sense that museums would look to NFTs as a potential source for new revenue. But how museums choose to use NFTs could significantly impact their digital transformation and have unforeseen implications that could potentially haunt them long into the future. I would encourage museums to follow Walt Disney’s advice and “not sign away anything they don’t know about.”

Source, The Economist

But first, what are NFTs? NFTs (non-fungible tokens) are rare collectible digital assets that are registered on the blockchain. NFTs have taken off primarily as a way to monetize natively digital goods like digital art, video game assets, and property/land in the metaverse. Because these goods have no physical component, they were historically difficult to buy and sell. By making digital assets ownable and giving them proven scarcity, NFTs have unlocked a new market for digital goods that exceeded $2.5B in the first half of 2021 alone.

In addition to selling natively digital goods as NFTs, many people have explored the process of minting or “tokenizing” physical objects into digital NFTs. The idea behind tokenizing a physical object, such as a painting, is that you could then own/buy/sell/lend that NFT as a digital proxy for the physical object.

While I have found that older generations often struggle with understanding why an NFT would have any value at all, this concept is rather intuitive for younger folks who grew up buying and selling video game assets, spending time with virtual reality, and hanging out in the metaverse.

So where does this leave museums? Museums own, protect, and share the world's most important cultural treasures. The obvious NFT play for museums desperate to raise money fast would be to tokenize the physical objects in their collections and sell off the official digital copies as NFTs to the highest bidders. The problem with this approach is that it requires museums to mortgage their digital future in the long run for a small payout in the short run.

Doni Tondo, Michelangelo - 1505–’06

In May, the Uffizi Gallery minted and sold a single edition NFT of Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo (1505–’06) for $170,000. The museum reportedly earned $65,000, splitting the profits 50/50 from the sale with technology partners Cinello for leveraging their patented DAW® (Digital Art Works) technology.

According to Cinello’s website, “All revenues from DAW® and from exhibitions are shared equally with our partners to ensure a new revenue stream without introducing any restrictions on ownership or current rights.” However, this statement shows a fundamental misunderstanding of the emerging NFT/metaverse culture.

Cinello are correct that the Uffizi is likely not legally signing away any digital rights, especially given that works like the Doni Tondo are technically in the public domain. The value of the NFT comes from the public perception that since the museum owns the physical work, it therefore would be the most respected authority to mint and sell the official NFT. But having sold this as a single edition, the Uffizi no longer has ownership over the NFT for the foreseeable future. Why does this matter? Because NFTs have become the standard format for owning digital goods, particularly in the metaverse.

Perhaps you are thinking, “Jason, you are a huge nerd. Nobody cares about your dorky NFTs and the metaverse.” But what you may be missing is that this combination of buying digital goods in NFT format for use in the metaverse is quickly becoming mainstream.

Shopify, the second-largest e-commerce solution behind only Amazon, just announced support for their 1,700,000 users across 175 countries to sell NFTs directly from their online stores. Last month, Facebook, with its 2.7B users, shared that it is betting its entire future on the metaverse. Zuckerberg defined the company’s “overarching goal” as “helping to bring the metaverse to life.”

Just as physical assets (drawings, paintings, sculptures, etc.) draw the public to physical museums, NFTs of their iconic masterworks will become the draw to museum’s digital properties in the metaverse long into the future.

What if instead of selling an exact replica of Doni Tondo, the Uffizi commissioned a digital artist to make an NFT inspired by the Doni Tondo? This would be a win/win in that the partnership would elevate the contemporary artist by associating them with the prestigious museum while allowing the museum to avoid digitally deaccessioning important artworks from their collection.

For example, the Italian CryptoArt duo Hackatao recently sold a series of NFTs inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing Head of a Bear, referred to as Hack of a Bear. By comparison, the combined sales from the Hack of a Bear NFTs significantly outearned the Doni Tondo NFT. The Hackatao work was done in partnership with Christie’s, who was auctioning off the actual da Vinci drawing. It is not hard to imagine how artists like Hackatao could also form similar partnerships with prestigious museums like the Uffizi for similar initiatives.

Head of a Bear, Leonardo da Vinci - (Around 1480)

Hack of a Bear, Hackatao - 2021

Museums may also want to consider experimenting with NFTs as an opportunity to reduce dependency on donations from ultra-wealthy patrons who often have problematic roots. Perhaps instead of selling a single-edition NFT of Doni Tondo for $170,000 — reinforcing the idea that art is only for the rich — the Uffizi also could have sold an edition of 1,700 NFTs for $100 each. At this price point, a larger number of patrons may have been able to participate in the sale, creating a shared sense of stewardship over the NFT, the physical work, and the museum (much like the TopShots NFTs have for NBA fans).

I recently had a chance to moderate a panel with a museum that has taken quite a different approach from the Uffizi. The Whitworth Gallery at Manchester University has teamed up with tech partner Vastari to launch an NFT inspired by William Blake’s watercolor etching Ancient of Days.

William Blake, Ancient of Days - 1827 (from the Whitworth)

The Ancient of Days NFT

Rather than minting and selling an exact replica of the original Blake work as an NFT, the team has decided to mint a very cool spectrographic scan of the work in an edition of 50 on the ecofriendly NFT marketplace Hic et Nunc.

The Whitworth views the Ancient of Days NFT as an open experiment, having launched it in conjunction with their upcoming 2023 exhibition “Economics the Blockbuster” and inviting the public to track the primary and secondary sales of the NFTs over the two years leading up to the opening of the exhibition. As part of the exhibition, the Whitworth institution intends to “work with a range of practitioners - from artists, writers and activists to environmentalists, bankers and technologists - to explore alternative economies.”

As a museum dedicated to using art for social change, the Whitworth views this NFT as part of their wider transformation. All proceeds from the NFT will be used in socially beneficial projects in partnership with communities, organizations, and constituents of its surrounding neighborhoods and networks. According to their website, these projects will focus on education, health, environment, and social cohesion.

I think the Whitworth and Vastari have pioneered some great best practices here that other museums could learn from. By choosing to mint the spectrographic scan of the work, the Whitworth cleverly avoids the premature digital deaccession of an important work from their collection. Issuing the NFT as part of an exhibition exploring economics gives the NFT purpose and context within the museum’s scheduled programing and public mission. The use of the spectrographic scan also adds a nice twist in that it highlights Whitworth’s work as a research institution. Opting to mint an edition of 50 instead of a single edition makes it easier to reduce the price per NFT and increase the number of patrons who can participate in collecting the work. Finally, they were thoughtful about deploying the NFT in a way that aligns with their mission to transform into an institution for social change.

The truth is that nobody knows for certain how things will turn out with NFTs in the future. But that alone is reason to use caution and to engage thoughtfully. I don’t mean to pick on the Uffizi — there are many museums following a similar strategy of digital deaccession. I was driven to write this post because I love museums and I see great potential for them to thoughtfully and creatively use NFTs for fundraising and to engage with their communities. I would just encourage them to think like Disney did when asked to sign over his television rights decades before TV became omnipresent and “not sign away something they don’t fully understand.”