Feel free to continue reading our 2018 predictions but please note that we have also recently published our 2020 art market predictions.

"A good forecaster is not smarter than everyone else, he merely has his ignorance better organized." - Anonymous

The Artnome team has spent a lot of time exploring the intersections of art, technology, and data over the last few years. In addition to building the world's largest art database of searchable catalogue raisonné, we have pioneered machine learning for visual search of artworks, used analytics to win fantasy art auctions, interviewed experts on how to use machine learning for art valuation, and leveraged computer vision to try and beat Christie's auction estimates using data.

Given our interests, experiments, and research over the last year, we thought we'd try our hands at making some predictions for the art market for 2018.

#1 Art by women will go up in value

Berthe Morisot

Après le déjeuner , 1881

Sold at auction for $10.9M in 2013

A recent study I read in Hyperallergic estimates that art by women sells for 47% less than work by men. While this is sad, I am not surprised, as our own Artnome research recently showed that you could buy the most expensive work by every major female artist for less than the price of a single Da Vinci painting. That said, I am extremely bullish on the potential for cultural shifts from the woman's march and the #metoo movement to positively impact how we value art by women. As a feminist, I operate on the assumption that there is no difference between men and women when it comes to creativity and quality of art. Smart collectors who agree with my premise will seize the opportunity to buy work at half off. It is both an amazing investment and a way to help correct the market by supporting female artists. Many people I have talked to have argued with me that the art world is very conservative and slow to change. This may be true, but I already see many encouraging signs.

As many have pointed out, such as the Guerrilla Girls, historically, retrospectives and one-person shows at major museums have been dominated by male artists.

Guerrilla Girls

How Many Women Had One-Person Exhibitions at NYC Museums Last Year?

In the last few years, though, we have seen retrospectives for Yayoi Kusama, Agnes Martin, Carmen Herrera, Alma Thomas, Marilyn Minter, to name a few. While women may not yet have achieved parity with men, it is promising that artists Vija Celmins, Adrien Piper, Sally Mann all have major retrospectives scheduled for 2018.

On the flip side, male artists and men of power in the art world are being called out for misogynistic behavior and sexual misconduct. The long list of male celebrities accused of sexual misconduct in 2017 is depressing, and the art world is not excluded. Two weeks ago, painter Chuck Close apologized (sort of) after facing allegations from several women that he sexually harassed them when they came to his studio to pose for him. The Chuck Close incident came on the heels of Knight Landesmen, the publisher of Artforum, stepping down after accusations of sexual harassment from 9 women.

Of course, misogyny in art is also not unique to 2017. Back in 2013, artist Georg Basilitz told a reporter from Der Spiegel that "Women don't paint very well." In a 2015 interview with the Guardian, he doubled down claiming "the market doesn't lie," leaving us with no doubt of his backward, sexist stance.

If the positive attention being brought to female artists could potentially increase the value of their work, how will the negative attention earned by some male artists potentially impact the perception of their work both culturally and economically? I don't think it can be positive based on how we have responded to top performers, actors, and musicians like Bill Cosby, Kevin Spacey, and others. Whether you or I agree or disagree with devaluing art for it either being perceived as misogynistic, racist, lewd, insensitive, or offensive, it is already happening. Look at these stories from 2017:

The Guggenheim pulled three works for "animal cruelty" from their show "Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World" under pressure from animal rights activists.

Native American protesters successfully lobbied for the removal and destruction of Sam Durant's sculpture "Scaffold" from the Walker Art Center Sculpture Park.

Public protests at the 2017 Whitney Biennale demanding they take down and destroy a painting of Emmitt Till by artist Dana Schutz.

An online petition to the MET calling for the removal of the Balthus painting Thérèse Dreaming was unsuccessful.

Of course it needs to be said that freedom of expression, fighting censorship, and addressing difficult subject matter are some of the most important functions of art in our society. Equally important is the public response, which sometimes includes protests and public outrage, as it should. Without public response, positive or negative, art risks getting locked in a dangerous self-indulgent echo chamber. The art-loving public are engaging, and are pushing back against the display of work they feel is either cruel, insensitive, or does not reflect the world they want to live in. I predict now more than ever, pressure on artistic institutions and collectors driven by a more participatory "social" media will increasingly reshuffle who we value and how we value art and artists.

#2 Consolidation of the online art market

Artsy brought in an additional $50M in Series D funding this year, bringing them to a total of $100M in funding. I am a big fan of Artsy, but when you take $100M in venture capital investment, the expectation is generally that you have a shot at providing a 10x return. In startup parlance, that means Artsy needs to hit "unicorn status" (valued at $1B+) to make good with investors. I am not sure that is possible. Here's why.

According to Hiscox online trade report 2017, online art market sales fared slightly better in 2016, reaching an estimated $3.75 billion, up 15% from 2015. The big three (Sothebys, Christies, and Heritage) generated $720M in sales in 2016, about 19% of the online art market. To put that in perspective, Leonardo Da Vinci's Salvator Mundi, a single painting, sold at Christie's in a live auction for $450M this year, whereas in the online art market, 79% of online art buyers spend less than $5,000 per piece when buying art. The most expensive artworks, as Christie's CEO Guillaume Cerutti recently pointed out, are likely to continue to be sold live and in person given how much money is at stake. So while Christie's currently has the largest online art sales, it currently amounts to just 1% of their total business.

Online auction company Auctionata/Paddle 8 took in nearly as much investment as Artsy ($95.4M), but unlike Artsy, they could not find additional investment in 2017 and were forced to shut down. Given the seemingly lower-than-predicted ceiling on the online art auction market and the large amount of venture capital invested, it would seem there are more players in the online art market than can be supported. For that reason, I predict further consolidation in the online auction market in 2018.

#3 Surrealism market will get a boost

Ask most people to name a surrealist artist and you are likely to hear Salvador Dali or Rene Magritte. I think both artists are going to have a big year in 2018 but for different reasons.

Of the 50+ artists Artnome tracked across social media platforms, Dali and Magritte finish in the top 12. The work of Dali and Magritte is perfectly tailored for sharing on social media. Surrealism is easier to consume than abstract art, more visual than conceptual art, and more hip than straight realism. If you don't think that popularity, exposure, and social media impact the value of an artist's market, look to Christie's masterful marketing campaign for Salvator Mundi, for which they spared no expense. We should also note that Picasso, Warhol, Van Gogh, Banksy, Monet, Basquiat, Mattise, Miro, Klimt, and Haring round out the top 12 of our Artnome social rankings.

Over 1,300 Salvador Dali works are sold at auction each year at an average of ~$16k. In the later years of Dali's career, he was seen as more of a businessman and a showman than an artist, putting out large editions of prints, often in the hundreds. My father-in-law owns a rather nice Dali print he purchased on a cruise ship a few years back - they are fairly easy to come by. I believe the high availability of Dali's prints and multiples may have unfairly pulled down the prices on his paintings, as well.

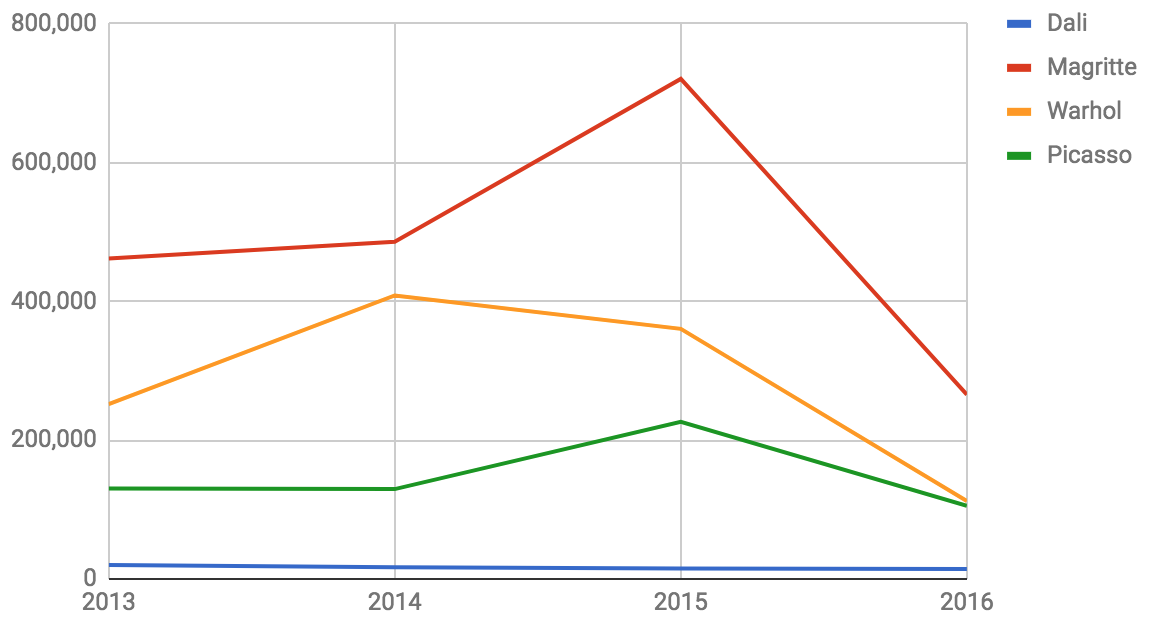

Volume of lots sold at auction by year

Volume of lots sold at auction by year. Data sourced from Art Price annual market analysis.

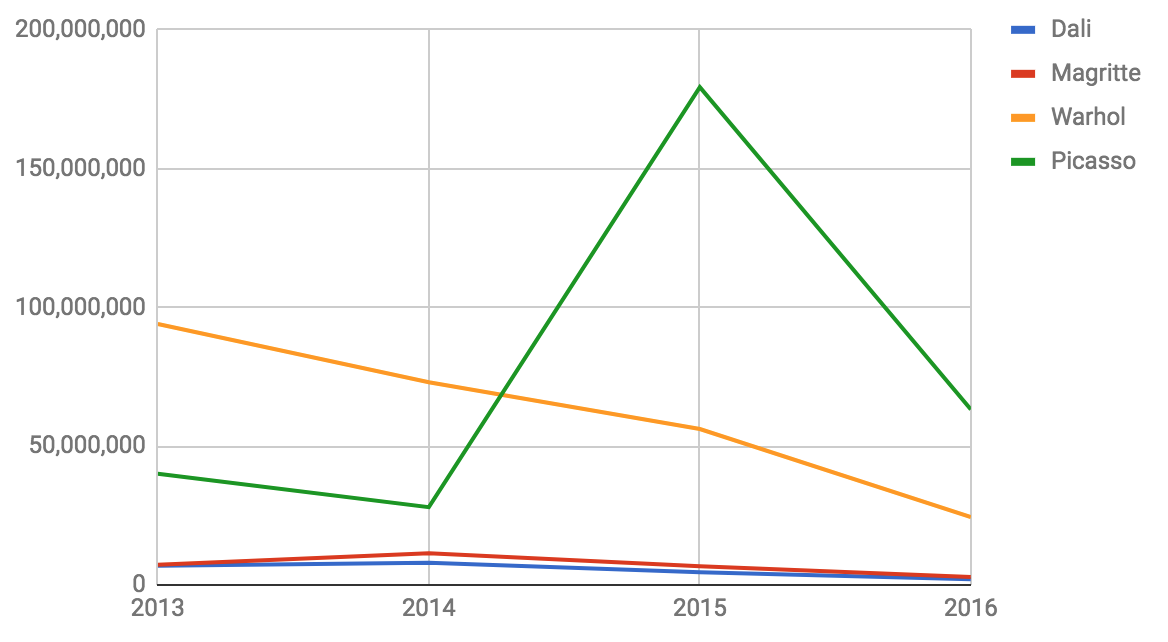

Average hammer price at auction by year

Average hammer price at auction by year. Data sourced from Art Price annual market analysis.

Hammer price of highest-valued work sold at auction

Hammer price of top work sold at auction. Data sourced from Art Price annual market analysis.

The good news is the Salvador Dali catalogue raisonné was recently finished and made publicly available online. The catalogue brings needed structure to the Dali market and sheds some light on a body of work that has historically been hard to nail down. Collectors can now consult the catalogue and purchase work that is guaranteed to be authentic. The catalogue recognizes 1,207 works by Dali, which is very reasonable when compared to the number of paintings created by other artists we have looked at.

2018 will also be a very exciting year for fans of Rene Magritte. As part of the 2018 class of artists entering into the public domain, all of Magritte's images will become copyright free. This will mean that lots of articles and blog posts should also increase the shareability of images of Magritte's work across social-media platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter. Magritte also has a major show at the SFMOMA which could also help to boost interest in his market.

Don't be surprised if we see a new auction record by one or both of these artists this year. At a minimum, I expect their total auction turnover to see an uptick, barring any major negative macroeconomic factors.

#4 There will be an art analytics revolution

The scouting scene from the movie "Moneyball"

There is a famous scene in the book/movie Moneyball where the scouts, most of them white men in their 50s and 60s, are sitting around the table analyzing baseball players. They are making their assessments based on a combination of their experience and what they see with their own eyes. In the story, the team's general manager Billy Beane, a former baseball player himself, questions if this approach, which has remained relatively unchanged for the last 100+ years, is the best way to evaluate talent. Beane brings in Paul DePodesta, a recent economics graduate from Harvard, as the new GM. DePodesta, to the chagrin of the scouts, applies a more statistically rigorous method to evaluating players called Sabermetrics. Despite the Oakland Athletics baseball team having one of the lowest payrolls, by leveraging a new data-driven approach to assembling a team, they became highly competitive.

The central theme of Moneyball is that the collective wisdom of the scouts is often wrong, and when augmented with a data driven approach, can be greatly improved.

Me being star struck at the chance of meeting Billy Beane.

A Moneyball-style analytical revolution in the art market is long overdue. Like the baseball-scouting process in Moneyball, the appraisal process in the art world has remained relatively unchanged for a hundred plus years and is ripe for disruption. Until recently, the problem has been lack of availability of core data. The most accurate information on the supply of artworks created by a given artist was locked up in rare printed books called catalogue raisonné. Artnome is three years into creating an analytical database of complete works across our best known artists that makes data on supply and makes it searchable for collectors. Our database, like boxscore databases in baseball or customer databases in business, provides a foundation for building valuable analytical insights.

It will take more than the Artnome database to spur an analytical revolution. Sotheby's, Christies, and other auction houses already make data on their auctions publicly available. They will need to go a step further and put it into a format like an API or a series of .csv files on GitHub to help inspire thousands of would-be analysts to build a community around the mining of this data. Similar revolutions happened in sport as leagues like the MLB, NBA, and NFL have made it increasingly easier to mine data on their sites for new insights on our favorite teams and athletes.

Making information more readily available will ultimately increase business for all the auction houses. A number of major museums have already figured this out, open-sourcing data on their collections, with many more headed in that direction. According to the Hiscox online trade report 2017:

Although the art market is still notoriously opaque when it comes to revealing prices, 88% of online art buyers find price transparency (that is, the clear labelling of prices and the possibility to check past and comparable prices) an essential ingredient when buying art online. 67% of hesitant art buyers said they would like access to an independent valuation report (up from 51% in 2015, and down from 68% in 2016).

There is a clear demand for more information from prospective buyers. They not only want data, they want to be educated on the market. The auction houses who do this best will be the most successful in the decade to come. Again from the Hiscox report:

52% of online art buyers state that content is important to their platform choice (up from 42% in 2016). This suggests that buyers are looking for more than just buying artwork. In fact, they are attributing significant value to the educational experience.

I believe the the largest auction houses have a chance to be the pace cars for the art-analytics revolution. They have all the data needed to connect artworks, artists, consigners, dealers, and buyers. The irony is that making their vast data troves on art and sales available to the public will allow them to collect much more valuable data on their customers preferences.

Christie's and Sothebys have been around for hundreds of years, which does not always translate into fast adoption of new tech trends. Whichever house can act more like a startup and teach the so-called elephant to dance has the best chance to win analytics battle.