There has been a lot of talk about AI (artificial intelligence) in the media over the last few months, but there are still a lot of signs that most people don’t really understand it. For example, 90% of people polled in a recent survey believe that “up to half of jobs would be lost to automation within five years.” Of course, experts in AI find this idea laughable.

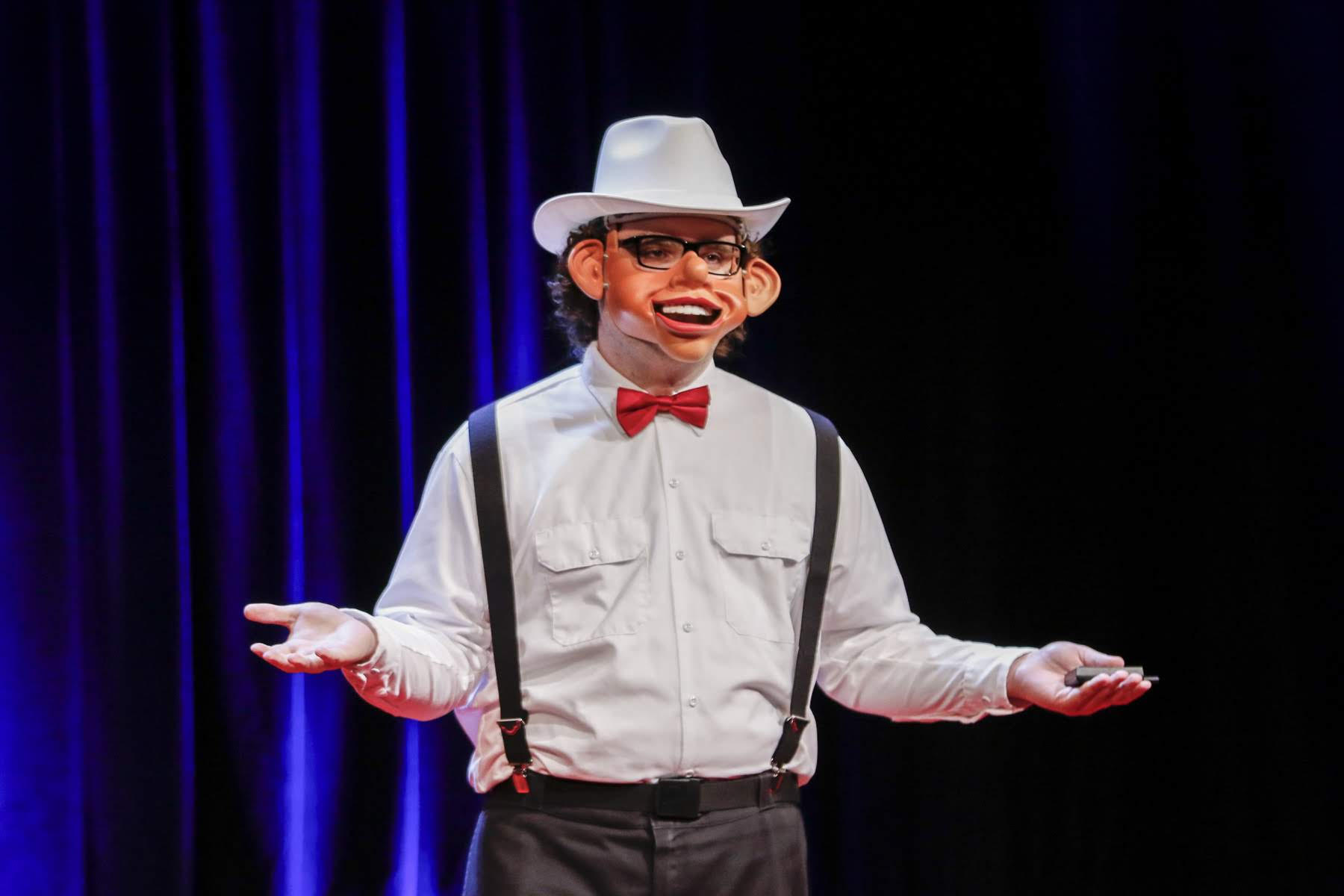

In an effort to help people better understand AI, we at Artnome are doing a series of interviews with artists who are exploring AI’s potential through art. In this post, we speak with artist Alexander Reben, whose work focuses on human/machine collaboration using emerging technologies. He sees these technologies as new tools for expression, and most recently trained an AI to give a TED Talk through a robotic mask on stage.

The Perfect TED Talk?

What if you could give the perfect TED Talk? How would you prepare for it? You could try to watch all 2,600 previous TED Talks that have been given on the main stage, but at around 18 minutes each, it would take you a month (watching day and night). Even if you could watch all the talks, as a human it would be hard to find the underlying structure or algorithm that makes a great TED Talk across such a large data set. However, this type of repetitive behavior and pattern identification is exactly what computers and AI do well.

And what does a TED Talk trained on all the previous TED Talks sound like? Well, it is actually pretty hilarious and entertaining.

For this TED Talk, Reben wrote an algorithm to break down the scripts for every past TED Talk given on the main stage into four roughly equal sections. “I basically hoped that the beginnings, middles, and ends of TED Talks would be somewhat similar,” said Reben of his approach. He then used this data set to train an AI to create multiple outputs for each of the four sections, selected the outputs he liked best, and combined them for his final presentation.

My goal was to make a three-minute talk so it would be Youtube length, so that was the constraint in terms of how many slides I was going to use. I wasn’t going to make a full 20-minute talk because you kind of get the point after several slides.

For the images on his slides, Reben used a separate algorithm that read the script for his talk, ran a search based on the content, and then choose relevant images from the internet. Even the positioning of the images on the slides was handled by a computer, as it was done by PowerPoint’s automated slideshow maker.

I asked Reben how he thought the AI performed as a collaborator in developing the script for the TED Talk.

The AI definitely can learn and perceive patterns at a scale that we don’t. This is something that feels like a TED Talk, but is not really a TED Talk. AI are good at making things that “feel” like things in the generative sense. It picks up on the soul of the data set - if we can call it that - and it can reproduce that soul. But it can’t pick up the creativity or make something coherent. I think that is why a lot of people are interested in AI art, because it is like seeing a pattern that is not really there and our brains try to fill in the gaps. It’s Frankenstein-ish.

If Reben’s AI collaboration is Frankenstein-ish, it is closer to Gene Wilder and Peter Boyle in Young Frankenstein than Victor Frankenstein and his menacing (if not misunderstood) monster originally depicted in Shelley’s novel.

Watching people try to train machines with limited capabilities to act like humans is… well… funny. Reben knows this very well. He entertains and educates us by essentially collapsing the gap between the public’s perception of AI as “job killer” and its current and actual capabilities as a fledgling tool that is heavily dependent on collaboration and direction from humans to perform even the most basic of tasks.

What Hollywood and the mainstream media have failed to teach us is that AI is currently like an infant: growing fast, but not very knowledgeable or skilled. Where most people play up (or down) AI’s capabilities, Reben has put AI out there in all its awkward glory on the most important stage of our time - the TED stage.

That said, Reben’s AI does a more respectable job at identifying patterns in TED Talks than we may pick up on with a single viewing. Let’s look closer at some of the more subtle, but repetitive and formulaic elements of a TED Talk that it was able to surface.

Start with a shocking claim: “Five Dollars can Save Planet Earth.”

Establish personal expertise and credibility: “I’m an ornithologist.”

Strike fear into the heart of the audience: “Humans are the weapons of mass destruction.”

Offer a solution based on novel technology: “A computer for calibrating the degree of inequality in society.”

Make a grandiose and unfounded proclamation: “Galaxies are formed by the repulsive push of a tennis court.”

Use statistics and charts to back it up: “Please observe the chart of a failed chicken coop.”

Give a simplified and condescending example for the “everyman”: “It’s just like this, radical ideas may be hard for everyone to register in their pants. Generally. And there’s a dolphin.”

Talk about the importance of your idea moving forward: “This is an excellent business because I actually earn one thousand times the amount of life.”

Describe potentially discouraging setbacks and roadblocks: “Let’s look at what people eat. That’s not very good food.”

Give promising evidence these barriers can be overcome: “We will draw the mechanics and science into the circuitry with patterns!”

Provide the audience an important takeaway question: “What brain area is considered when you don’t have access to certain kinds of words?”

End with a pithy and folksy conclusion: “Sometimes I think we need to take a seat. Thank you.”

Don’t get me wrong. I’m a TED Talk addict. In fact, I use many of the devices and formulas in TED Talks in my own writing. But following formulas in writing does not make me a great writer any more than learning the Macarena makes me a great dancer. Reben’s talk is giving us a cautionary tale: formula is the enemy of great public speaking, not the recipe for it.

Reben’s performance embodies this by delivering a presentation that is literally comprised of every TED Talk ever given, but which stylistically breaks from all known Talk formulas through the use of a machine-written script and the delivery through a robotic mask. Reben is not giving a TED Talk to give a TED Talk; he is co-opting the TED stage and TED brand as cultural material for creating his own art.

The results are hilarious, but there is also a double-edged realization that there is something fundamental about great public speaking that cannot be reduced into easy-to-learn formulas and thus replicated by AI. You may become a better speaker with practice, but it is human creativity and charisma that make a great presentation (even if many of us wish it were more formulaic and therefore attainable).

Reben’s TED Talk is only the latest in a long line of compelling works where he trains machines to perform human-ish activities that are ultimately void of real meaning or substance. His machines are like small children going through the motions of baby talk, making noises and gestures without quite understanding what they mean yet, and it is both haunting and beautiful to watch.

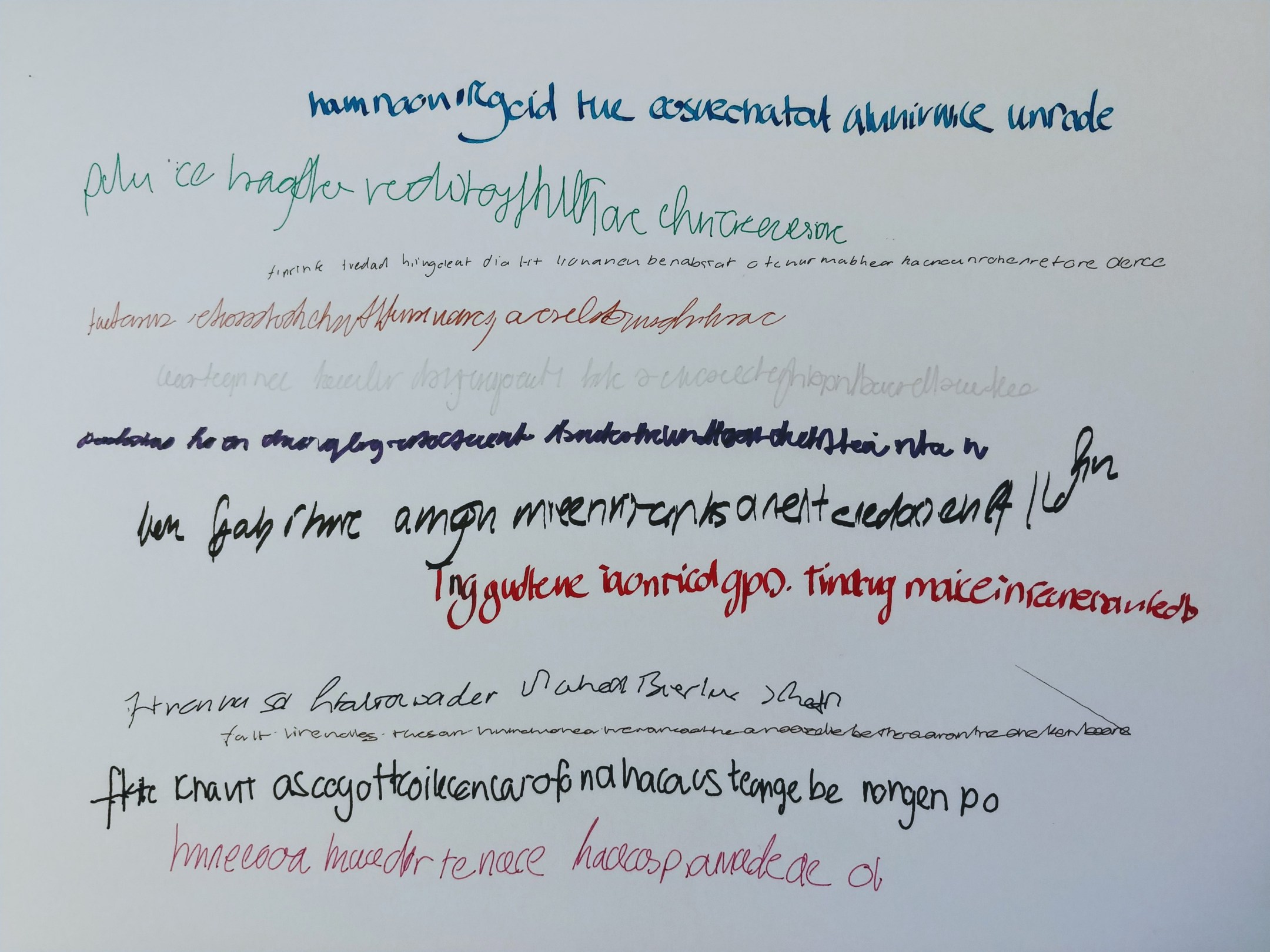

We see this duality in Reben’s Synthetic Penmanship project for which he put in thousands of samples of handwriting into a model and then got a robot with pens to try to make language. This model knows nothing about language, but you can see that it tries to create shapes that look like characters used in written English.

As Reben describes it:

All it knows is shapes. Here it tries to make this pseudo language thing, which is endlessly fascinating to me. It’s a computer trying to be human, but it doesn’t know anything about humanity or why it’s making these shapes. It just becomes so beautiful. The action of the robot doing it with these real pens is just this meditative human/machine spiritual connection.

My favorite work by Reben extends this idea of human-esque communication by training AIs on celebrities’ voices, and in some cases, adding them to video. Reben fed celebrity voices into an algorithm, training it to make sounds that sounded like celebrities, but similar to his synthetic penmanship project, they had no content of English in them.

The celebrities include John Cleese, George W. Bush, Stephen Colbert, Barack Obama, and Bob Ross. According to Reben, Ross in particular had a very “familiar deep tone to his voice.” He found it extremely interesting how the machine could mimic the soul of someone’s voice without understanding language whatsoever. “I could have fed it in the sounds of train horns and it would have done the same thing,” but this did it with language.

At that same time, Reben had been investigating the Deep Dream algorithm which people had been applying to photos and videos. It dawned on him that combining his AI speech patterns from celebrities with Deep Dream video could be pretty interesting. He chose Bob Ross because the act of someone painting was itself a creative process. Not only that, but as you are painting, you are building up an image, and that is something the Deep Dream code can really mess with. “As you add more and more shape to this image, the things it was seeing would get more and more complicated,” said Reben.

When I first saw Reben’s Deeply Artificial Trees go viral last year, it immediately hit me that Reben was collaborating with algorithms to produce an homage to the most prolific but oft misunderstood algorithm artist of all time. The high-art world shuns paintings by Bob Ross and his students because they are formulaic by design. Ross sought to make it easy enough for anyone to feel like a painter, and did so by breaking it down into simple steps. But like Reben’s AI TED Talk and Synthetic Penmanship project, Ross’ paintings have the formula of painting down. However, they lack the depth of thought and exploration we seek in works by master painters. They are in some senses robotic.

Ross is rejected by the traditional art world as irrelevant because if his paintings can be made so simply that anyone can produce them, then they are no longer special. This same line of thinking is of course important when considering generative or algorithmic art made in collaboration with AI. The problem being that if a computer can produce a work in a certain style, nothing should be stopping it from producing thousands or millions more similar works in short order.

For example, when I first saw a Deep Dream image, I was in love. I thought this algorithm rivaled the work of great surrealists like Salvador Dali. But then I discovered an app where I could easily make my own Deep Dream image from any photograph. At first it was intoxicating, and I made like twelve in the first few hours. But once I realized how easy it was the achieve the Deep Dream effect and how everyone now had access to it (it was all over Instagram), it lost its novelty.

Reben points out that he was exploring Deep Dream pre-appification of the algorithm, but also maintains a healthy attitude towards it.

Back then there weren’t as many tools out there as there are now to use Deep Dream. It really was a tool kit that was extremely interesting to me, like a new type of paintbrush. And yeah, the first time paint was invented, if you did anything with paint it was probably pretty amazing, but after a while, paint just became a tool like any other. Deep Dream is now available as a push-button filter, it is just a tool like any other and you can use it to do boring stuff or interesting things. The first few people who use any tool will get a lot of attention because it is so novel and new, but after that first wave, you have to do something really interesting with that tool set to move forward.

The brilliance of Reben’s Artificially Deep Trees is that it really is a human/machine collaboration rather than just the machine itself doing its thing. Reben creates the audio and curates the imagery resulting in something artful and engaging (as evidenced by its popularity). The magic for me here is that Reben combines two formulas for producing mass-produced kitsch imagery, Deep Dream and Bob Ross, and somehow creates a unique and compelling artwork from them. It is Reben’s human contributions to framing, curating, and editing the work, and not the execution of Ross’s or Deep Dream’s algorithms, that makes this a relevant and timeless work of art. As with Reben’s TED Talk, Deeply Artificial Trees highlights the idea that human creativity is irreplaceable, essential, and currently undervalued as we slowly march into a world of increased automation. As Reben describes it:

AI is really a tool that a human is using rather than the machine itself having all the creative power to it. My curation of the material Deep Dream is applied to, my curation of the voice, my curation of the edit — all those things were human, that was my side. Then there is a computer side, as well. Everyone is worried that AI is going to replace humans, but I think we are really going to see a human/computer collaborative future.

While I see several clear threads running through all of Reben’s work, I was eager to capture more of his thoughts, so I asked Reben to help me summarize the ideas, themes, and explorations behind his projects, starting with the TED Talk:

It has a structure of a pattern, the same way that the Stephen Colbert sounds like him but has no meaning, the handwriting makes English that has no meaning. This thing made a TED Talk that has no meaning. It has the structure of what it is. Our brains are pattern-recognizing machines. When there are patterns, that is soothing to our brains, but when there’s no content, it creates a dichotomy. I think that is what pulls people in and then scares them a bit. It’s a little bit grotesque.

I followed up by asking Reben if there are certain things that will always be in the domain of human creativity, like the charisma required to give a great TED Talk.

The real question is can you find a data set of “charisma.” What does that look like? It may not even be a tech problem so much as it is a training problem of a model. With a good enough data set, who knows what you could do, especially given how fast this stuff is moving. I think we’ll probably get good enough at some point to fake a lot of that, is my guess. So then maybe the more philosophical question is, is it better to have a human to do it than a machine if you can’t tell the difference? Is there inherent value of humanity in creativity versus something that’s just algorithmically made? If there is a distinction, that is a very human distinction; it’s not a very practical distinction. Meaning, if you can’t tell the difference, then it doesn’t actually matter.

An interesting thought experiment I came up with when I was talking to a philosopher was, “We can make a GAN to generate, say, comedy. Can we make a GAN to generate a new genre that we’ve never thought about before?” If you zoom out, “Can AI invent, say, a new academic topic that our brains as humans have never thought of before?” Keep zooming out and ponder if AI can create a new way of thinking. So if we don’t make an AI that could be, say, charismatic… maybe an AI will come up with something that we can’t actually understand which is a description of the world that is as complicated as charisma but is something that is completely different and unique to a computer. But yeah - a lot of stuff right now comes down to good data sets too.

What I love about Reben’s response here is that it highlights a quality that all of my favorite AI artists share: a sober and realistic appraisal of the current AI capabilities which does not dampen their imaginations for a fantastic future for AI that is near limitless.

In addition to his initial curated AI TED Talk, Reben is working on 24-hour autonomous TED Talks that will use text to speech. Be sure to keep an eye out for them. Other new works from Reben that I encourage you to check out include his AI Misfortunes (some great examples shown below). These fortunes are made by an AI which learned from fortune cookies which Reben describes as producing a type of “artificial philosophy.” He then curates phrases from an AI and chooses typography and colors to help amplify and emphasize the message before producing physical posters as the final step of the collaboration.

AI Fortunes - Alexander Reben

AI Fortunes - Alexander Reben

AI Fortunes - Alexander Reben

Also check out this sneak peak of Reben’s balletic three-hour piece of people training AI by showing their web cams their shoes. The ultimate in human/machine collaboration. It is really a 3D scan, which is why they are rotating everything, but Reben took the color images and re-assembled them back into videos. “It struck me as a type of performance people were doing to train an AI,” shared Reben. “I did not quite get it at first, but an hour later I found myself hypnotized.”

Reben is represented by the Charlie James Gallery in LA and has several shows coming up in 2019. If you are near any of these venues, I highly encourage you to check out his new work in person and meet Alexander if you have the chance.

Vienna Biennale, Vienna, Austria

stARTup Art Fair Special Project, Los Angeles, CA

V&A Museum of Design, Dundee, Scotland

MAK Museum, Vienna, Austria

Museo San Telmo, San Sebastián, Spain

MAAT, Lisbon, Portugal

MAX Festival, San Francisco, CA

Boston Cyberarts Gallery, Boston, MA

You can learn more about Reben’s latest works at areben.com. And as always, if you have questions, feedback, or ideas for articles for Artnome, you can always reach me at jason@artnome.com.