In May of 2015, Alex Mordvintsev’s algorithm for Google DeepDream was waaay ahead of its time. In fact, it was/is so radical that its “time” may still never come.

DeepDream produced a range of hallucinogenic imagery that would make Salvador Dali blush. And for a month or so, it infiltrated all of our social media channels, all of the major media outlets, and even became accessible to anyone who wanted to make their own DeepDream imagery via a variety of apps and APIs. With the click of a button, I turned a photo of my wife into a bizarre gremlin with architectural eyes and livestock elbows.

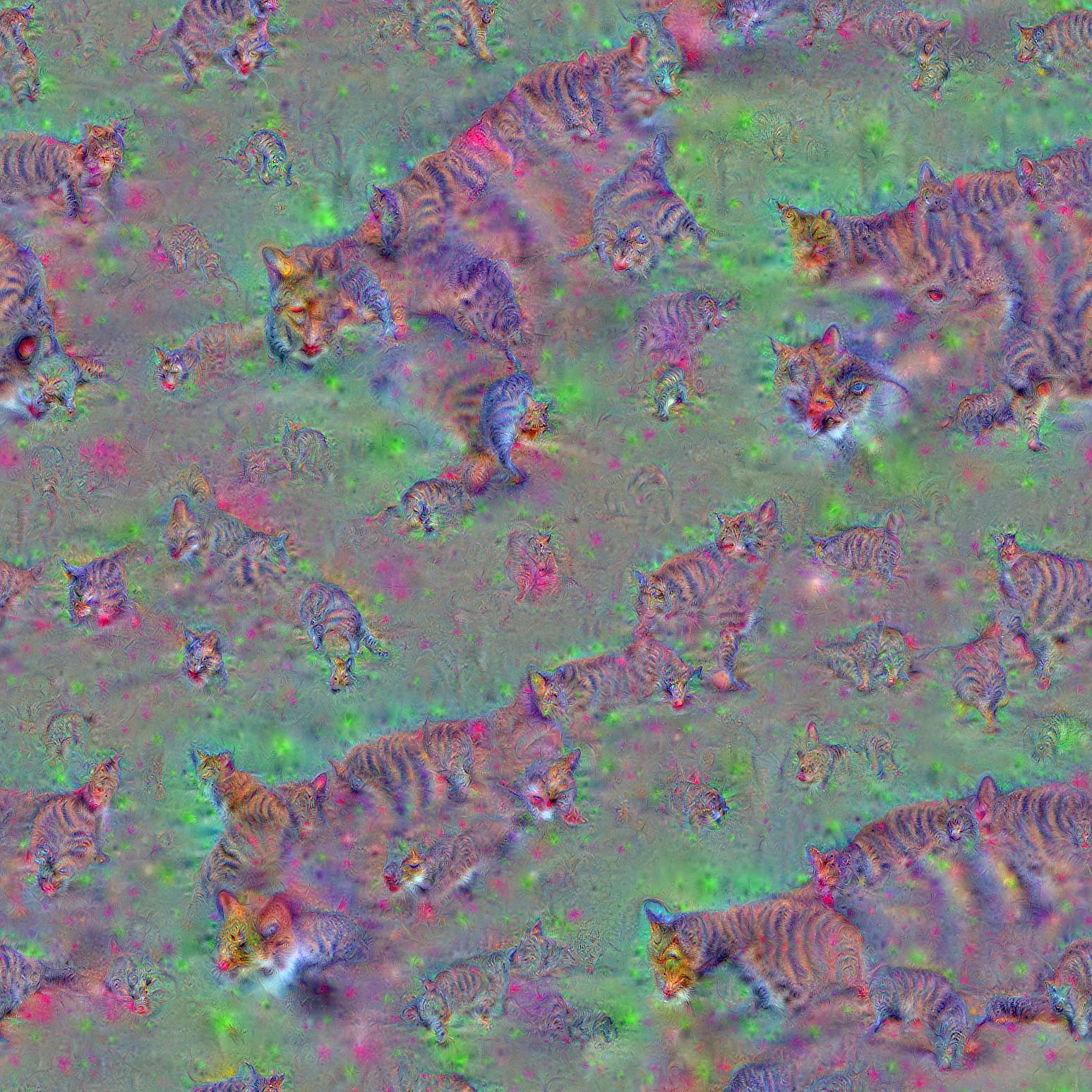

Image I made using a DeepDream app in August, just three months after it was invented by Alex Mordvintsev

And then — “poof” — DeepDream just kind of disappeared. It is the nature of art created with algorithms that when the algorithms are shared with the public, the effect quickly hits a saturation point and becomes kitsch.

I personally think DeepDream deserves a longer shelf life, as well as a lot of the credit for our current fascination with machine learning and art. So when Art Me Association, a non-profit organization based in Switzerland, recently asked if I wanted to interview Alex Mordvintsev, developer behind the DeepDream algorithm, I said “yes” without hesitation.

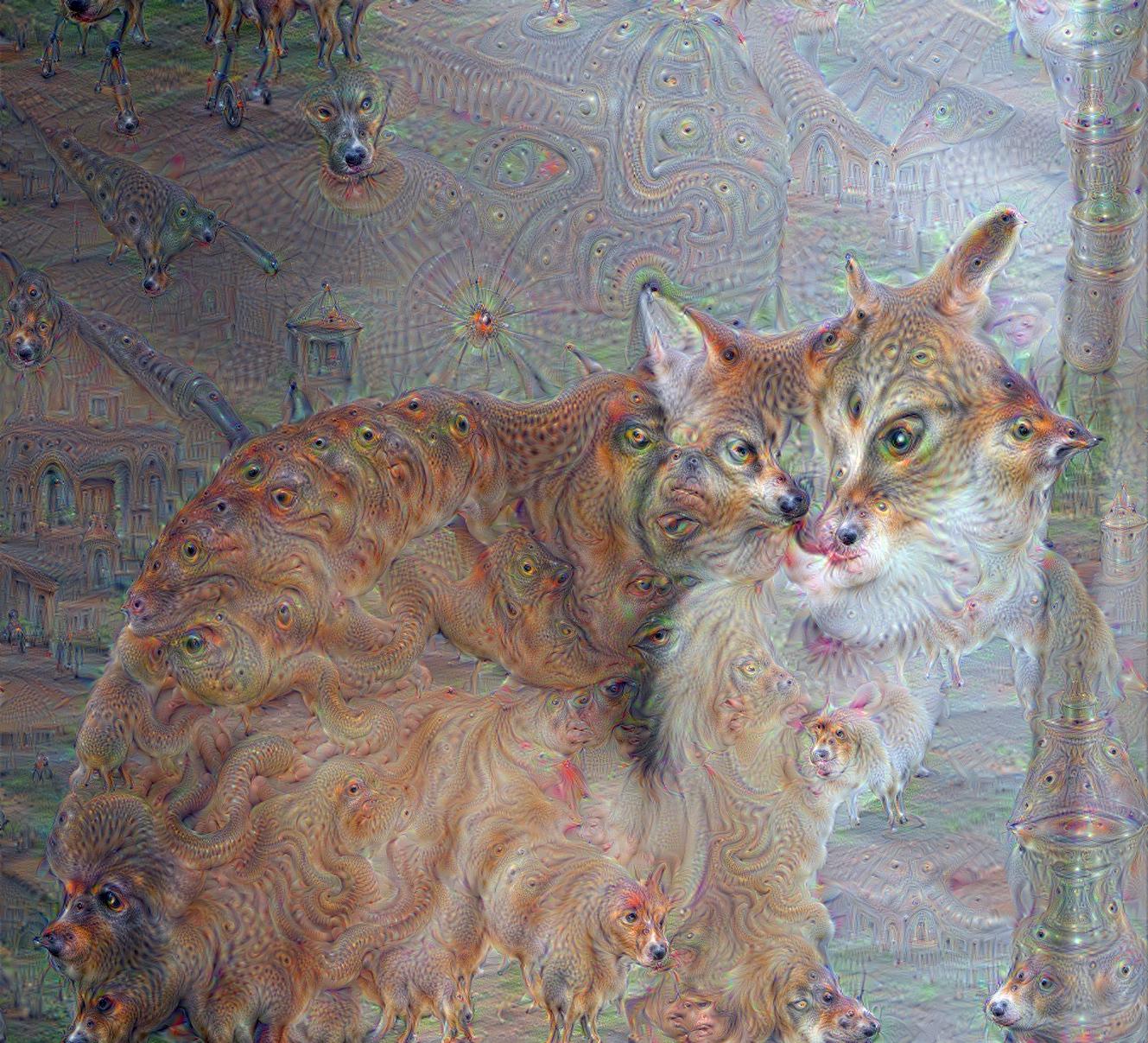

And when Alex shared that he recently found the very first images DeepDream had ever produced and then told me that he had never shared them with anyone, I could hardly contain myself. I immediately asked if I could share them via Artnome. Well, to be honest, I first asked if I could buy them for the Artnome digital art collection (collector’s instincts), but it turns out Google owns them and has let Mordvintsev share them through a Creative Commons (CC) license. Something tells me that Google probably doesn’t need my money.

Father Cat, May 26, 2015, by Alexander Mordvintsev

For me, Mordvintsev’s earliest images from May, 2015, are as important as any other image in the history of computer graphics and digital art. I think they belong in a museum alongside Georg Nee’s Schotter and the Newell Teapot.

Custard Apple, May 16, 2015, by Alexander Mordvintsev

Why do I hold so much reverence for the early DeepDream works? DeepDream is a tipping point where machines assisted in creating images that abstracted reality in ways that humans would not have arrived at on their own. A new way of seeing. And what could be more reflective of today’s internet-driven culture than a near-endless supply of snapshots from everyday life with a bunch of cat and dog heads sprouting out of them?

I believe DeepDream and AI art in general are an aesthetic breakthrough in the tradition of Georges Seurat’s Pointillism. And to be fair, describing Mordvintsev’s earliest DeepDream images as “just a bunch of cat and dog heads emerging from photos” is as about as reductive as calling A Sunday on La Grande Jatte “a bunch of dots.”

That Mordvintsev did not consider himself an artist at the time and saw these images as a byproduct of his research is not problematic for me. Suerat himself once shared: “Some say they see poetry in my paintings; I see only science.” Indeed, to fully appreciate Mordvintsev’s images, it is also best to understand the science.

I asked Mordvintsev about the origins of DeepDream:

The story behind how I invented DeepDream is true. I remember that night really well. I woke up from a nightmare and decided to try some experiment I had in mind for quite a while at 2:00 AM. That experiment was to try an make a network to add details to some real image to do image super resolution. It turns out it added some details, but not the ones I expected. I describe the process like this: neural networks are systems designed for classifying images. I’m trying to make it do things it is not designed for, like detect some traces of patterns that it is trained to recognize and then trying to amplify them to maximize the signal of the input image. It all started as research for me.

I asked Alex what it was like to see his algorithm spread so quickly to so many people. I thought he might have regretted it getting “used up” by so many others, but he was far less shallow than me in this respect and took a broad-minded view of his impact:

I should probably have been involved in talking about it at that moment, but I was more interested in going deeper with my research and wanted to gain a deeper understanding of how things were working. But I can’t say that after three years of research that I understand it. So maybe I was over-excited in research at the moment.

I think it is important that everyone can participate in it. The idea that Iana, my wife, tries to convey is that this process of developing artificial intelligence is quite important for all the people and everyone can participate in it. In science, it isn’t about finding the answer, it is more about asking the right question. And the right question can be brought up by anybody.

The way I impacted society [with DeepDream] is that a lot of people have told me that they got into machine learning and computer vision as a result of seeing DeepDream. Some people even sent me emails saying they decided to do their Ph.D.s based on DeepDream, and I felt very nice about that. Even the well-known artist Mario Klingemann mentioned that he was influenced by DeepDream in an interview.

Indeed, I reached out to artist Mario Klingemann to ask him the significance of DeepDream for him and other prominent AI artists. He had this to say:

The advent of DeepDream was an important moment for me. I still remember the image of this strange creature that was leaked on reddit before anyone even knew how it was made and knew that something very different was coming our way. When the DeepDream notebook and code was finally released by Google a few weeks later, it forced me to learn a lot of new things; most importantly, how to compile and set up Caffe (which was a very painful hurdle to climb over), and also to throw my prejudices against Python overboard.

After I had understood how DeepDream worked, I tried to find ways to break out of the PuppySlug territory. Training my own models was one of them. One model I trained on album covers which, among others, had a "skull" category. That one worked quite nicely with DeepDream since it had the tendency to turn any face into a deadhead. Another technique I found was "neural lobotomy," in which I selectively turned off the activations. This gave me some very interesting textures.

Where I had seen sharing the code to DeepDream as a mistake, as it quickly over-exposed the aesthetic, Mordvintsev saw a broad and positive impact on the world which would not have been possible without it being shared. Mordvintsev also took some issue with my implication that DeepDream was getting “old” or had been “used up.” It turns out that my opinion was more a reflection of my lack of technical abilities (beyond using the prepackaged apps) than a reflection of DeepDream’s limitations as a neural net. He politely corrected me, saying:

Maybe you played with this and assumed it got boring. But lately, I started with the same neural network, and I found a beautiful universe of patterns it can synthesize if you are more selective.

I was curious why so many of the images had dog faces. Alex explained to me that he was using a pretrained network called ImageNet, a standard benchmark for image classification that was established around 2010. ImageNet includes 120 categories of dog breeds to showcase “fine-grained classification.” Because ImageNet dedicates a lot of its capacity to dog breeds, it triggers a strong bias in the data. Alex points out that others have applied the same algorithm to MIT’s Places Image Database. Images from the MIT database tend to highlight architecture and landscapes rather than the dogs and birds favored in the ImageNet database.

I asked Mordvintsev if he now considers himself an artist.

Yes, yes, yes, I do! Well, actually, we are considering my wife and I as a duo. Recently, she wanted to make a pattern for textiles and wanted a pattern that tiled well, and I sat down and wrote a program that tiled. And most generative art is static images on screen or videos, and we are trying to get a bit beyond that to something physical. We recently got a 2.5D printer that makes images layer by layer. I enjoy that a lot. But our artistic research lays mostly in this direction: moving away from prints into new mediums. Recently, we had our first exhibition with Art Me at Art Fair Zurich and we had sponsorship from Google. We are interested in showing our art to the world and trying to explain it to a wide audience.

Alex and Iana Mordvintsev Prepping to show their latest work at Art Fair Zurich

While I appreciated DeepDream from the beginning, I felt it became kitsch too quickly as a result of being shared so broadly. Speaking with Alex makes me second guess that. It’s now clear to me that Alex did the world a service by making his discovery so broadly available and that he still sees far more potential for the DeepDream neural net (and he would know). There are some critics who just don’t “get” AI art, but as Seurat said: “The inability of some critics to connect the dots doesn't make Pointillism pointless.”

Above: Alex Mordvintsev’s NIPS Creativity Art Submission

As always thanks for reading! If you have questions, suggestions, or ideas you can always reach me at jason@artnome.com. And if you haven’t already, I recommend you sign up for the Artnome newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest news.