The world will take over 1 trillion photographs in 2018. Almost all of them will remain digital and never be printed. Blockchain enables us to provably buy, sell, trade, and destroy those digital or "virtual" photographs as if they were all physically tangible photographic prints. A step further, you can now edition each virtual photograph, producing and selling anywhere from one to one million+ copies of each virtual photo. Our ability to track and prove the scarcity of these virtual photos will greatly eclipse our ability to prove and track scarcity and authenticity of physical photographs and artwork. This is not a prediction, it is already happening, and virtual photos are selling for as much as $1million.

If you are new to blockchain you may want to read one of my earlier articles on the blockchain art market. In it, I outline the basics and explain that all of art will be changed from the creation process through to consumption by the introduction of blockchain technology. But “art” is an ambiguous all-encompassing term, and not all art will be impacted by the blockchain in the same way. For example, blockchain changes photography in different ways than sculpture, painting, and other inherently physical media. I am putting a few reasons why I believe this to be true upfront.

Most photography already starts and ends digitally.

Photography is generally a flat medium that lends itself to presentation on screens.

New ultra high-resolution screens designed for sharing fine art are narrowing the fidelity gap between analog and digital representation.

Tokenization of art on the blockchain yields “editions,” a concept already well understood within photography.

Blockchain improves the existing tools for assuring the limited nature of editions by decentralizing the information and introducing digital scarcity.

There is a high degree of familiarity with photography as an art form, as much of the world's population has taken a digital photo on a smartphone (70% of the world population is estimated to own a smart phone by 2020).

Digital consumption of photography has become mainstream via Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, etc.

In this article we take a closer look at what makes photography uniquely suited to benefit from blockchain technology. We speak with several professionals with diverse backgrounds in the professional photography trade, including the artist behind the world's most expensive CryptoArt ($1m Forever Rose), a specialist from Christies' Photographs department, the founder of a company changing how luxury goods (including fine-art photography) are consumed, and a lawyer with expertise in artists' rights management and blockchain smart contracts.

But first, let's look at the rapid change that has occurred in photography in the last 20 years and define the core concepts of "decentralization" and "digital scarcity" as they apply the blockchain and photography.

The Digitization and Explosive Growth of Photography

Photography has gone through dramatic change in the last two decades. First, shifting from almost entirely film based to almost entirely digital.

Second, since the year 2000 the number of photos taken annually has jumped 15x from 80 billion to 1.2 trillion, an astonishing increase of 1,400%.

The near complete digitization of photography combined with the explosion in the number of photographs taken means photography represents perhaps the largest opportunity for applying blockchain to art. This has not gone unnoticed by established corporations in the photography space.

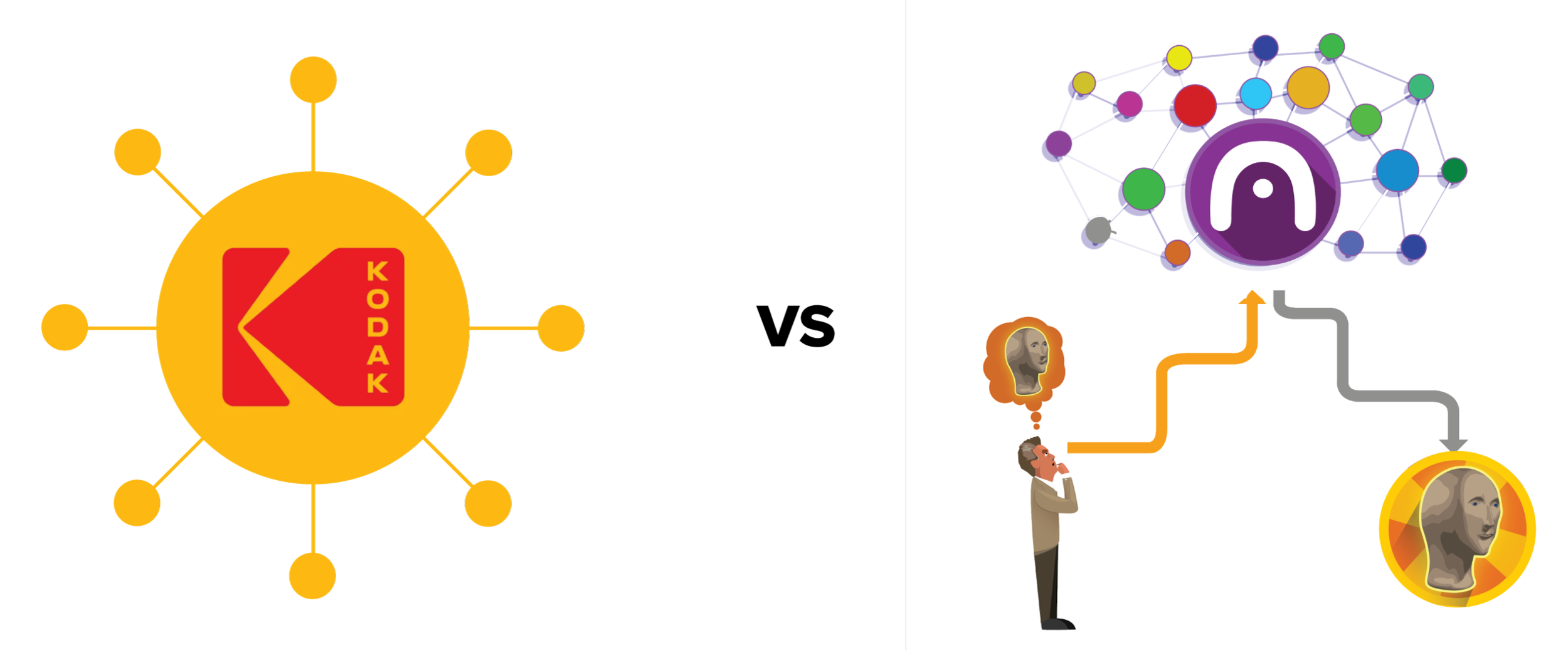

Blockchain Solutions for Photography: Centralized vs. Decentralized

Earlier this year I wrote a short article about Kodak’s announcement that they would be issuing a "Kodak Coin" on the blockchain as part of their solution for helping photographers to manage image rights. I don't believe they will be successful, as Kodak managing blockchain-based solutions for photography would be like Bank of America managing the Bitcoin blockchain.

This brings us to another core concept of blockchain: centralization vs. decentralization. The blockchain itself is a decentralized ledger (or list of transactions). But beyond the structure of the technology, the crypto community embraces decentralization of application governance (DApps). I would consider Kodak to be on the centralized side of this spectrum for a few reasons:

Kodak is, by design, a politically centralized entity (CEO has final say in decisions).

Kodak requires paid registration in their paid KodakOne platform in order to leverage their image-recognition software to enforce photographic copyright.

Kodak limited participation in their ICO to investors that “satisfy the investor qualification requirements” which is antithetical to the spirit of blockchain.

Let's look at the Archetype.mx model to better understand what a decentralized solution looks like (vs. Kodak's more centralized model). Archetype allows anyone to create their own cryptographic tokens representing memes, art, or any kind of information imaginable (photographs, in our case). Key elements that make Archetype a decentralized solution include:

Archetype has no CEO or executive team. The users invest in the protocol and reap the rewards if the value goes up through usage and network effect.

Archetype.mx does not charge users for any of the benefits of their platform

Archetype's IBO (Initial Burn Offering) is not restricted based on net worth. You can participate by investing as little as 0.0000000000000000001 ETH (fractions of a penny).

By leveraging Archetype's platform, any photographer will be able to tokenize their photographs into an essentially unlimited number of editions and have trackable proof of their digital scarcity.

But what does digital scarcity mean in relation to digital editions of photographs?

Blockchain and Photographic Editions: Physically Rare vs. Digitally Rare

Henry Fox Talbot - August, 1835

Latticed Window at Lacock Abbey

A positive from what may be the oldest existing camera negative.

Now let’s examine a second key concept, digital scarcity and physical editions vs. digital editions.

Like CryptoArt and other emerging art on the blockchain, photography was not always accepted broadly as a fine art form. Editioning photographs by artists was actually not commonplace until about the 1980s. It is now standard practice for contemporary photographers who wish to create markets for their work.

These "editions" are typically presented in one of two formats, "limited" and "open". Limited editions provide collectors a way to purchase a provably rare physical print. With limited edition prints, the artist agrees to stop making prints after a given number are produced and the negatives are often destroyed once the edition is complete. This protects against additional editions of the photograph being released which could negatively impact the investment of the collector. The second format, open editions, simply means the print can be produced in an unlimited number.

Until the blockchain and digital scarcity, you could not produce digitally rare editions of photographs the way you could with physical limited editions of photographic prints. One of the most important innovations in blockchain for art is that you can now treat photographs that exist only digitally as if they were physical, and create provably rare, digitally scarce editions. Two popular non-photographic examples of digital scarcity you may be familiar with are Bitcoin and CryptoKitties. In both cases, the owner has cryptographically verifiable ownership and control over the good until it is destroyed, lost, or purchased by another owner. The important thing to understand is that this provides a new paradigm for digital goods, once infinitely copyable, to be bought and sold as if they were rare physical goods.

Perhaps this sounds like science fiction that only a small group of CryptoCurrency enthusiasts would ever pursue? Will this idea ever catch on with the mainstream art world? Based on my conversations with folks at the major auction houses (Sothebys and Christie's), I would say it already has. Anne Bracegirdle, Christie’s Associate Vice President of Photographs, is a blockchain enthusiast (and CryptoArt supporter) and has an optimistic view of the blockchain's potential for the photography market.

We are frequently asked about the process of editioning photographs and how we know, with certainty, that editions will not be recreated. Blockchain provides immediate, inherent answers to these questions and appears to be a natural fit for editions. Providing transparency and guaranteed security with editions would dissolve any sense of related concern from potential buyers. If secured on blockchain, all new prints offered on the market would be recorded and accessible to, theoretically, the artist’s gallery, clients, and art market professionals. These changes would be instantly visible to all, creating an organic ‘regulation’ of sorts. This transparency benefits artists too, who generally do not wish to dilute their market or inadvertently deter potential buyers.

Not only would this transparency assure buyers, it would serve everyone interacting with a particular piece – an auction house representative, dealer, the artist and owner. The more available and secure this information, the easier the piece will be to research and catalogue correctly. There will be less room for human error and uncertainty regarding the numbering process; we would also know if a particular edition is sold out. Removing doubt or confusion surrounding a potential purchase is beneficial for all parties involved and often necessary for a successful transaction. We want to empower and educate clients, to help them feel more comfortable with an inherently complicated medium and market. This is one of myriad ways blockchain can foster that empowerment within the art market, resulting in more – and more seamless – transactions.

But what does purchasing a “Digitally Rare Photograph" look like? Let's look at one of the best known examples.

Kevin Abosch's $1m "Forever Rose"

The Forever Rose by artist Kevin Abosch sold on Valentines Day for $1 million. The sale captured the headline "...The World's Most Expensive Virtual Art".

I had a chance to interview Kevin about his thoughts on the Forever Rose and the potential for blockchain and art. Kevin explained how the Forever Rose project came about, but wanted to start with his I Am A Coin project to provide the proper background. The overview of I Am A Coin according to his website:

World-renowned visual artist Kevin Abosch has created 100 physical artworks and a limited edition of 10 million virtual artworks entitled "IAMA Coin"

The physical works are stamped (using the artist's own blood) with the contract address on the Ethereum blockchain corresponding to the creation of the the 10 million virtual works (ERC-20 tokens)

In my interview with Kevin, he provided more background and detail on both the I Am A Coin project and his Forever Rose. In his words:

My I Am A Coin project really is the culmination of everything I am about: Identity, existence, value, human currency. And it's just a function of me being an artist with a bit of success and feeling a bit commodified... as I have said in the press already. And I started to imagine myself as a coin. In fact, I started looking at of all of us as coins, and wondered what that would look like, all of us as coins in the hands of the masses, and wanted to do that in some kind of elegant way. So naturally I started to look at the blockchain. And this was on the heels of months of friends of mine in tech asking, "Hey, should I do an ICO?" and I was like, "Fuck ICOs" for a number of reasons. Aside from that, there is clearly a lot of regulatory stuff happening and you do not want to be on the wrong side of that.

But still I was thinking, "I'm an artist, I'm not trying to raise money for a company, so I will tokenize myself..." and you saw how I did that - the blood, the physical work, and the virtual work of my I Am A Coin project. It has been a bit of a challenge for some people as to how an ERC20 token itself can be a piece of virtual art, or it is a placeholder for art, whichever you prefer. I think when it comes to blockchain plus art, this would be a rather extreme position.

Now that I had the background on Kevin's I Am I Coin project, I asked him to share a bit more about his Forever Rose.

So I thought about a symbol of love, and I gave in to my worst desire, which is one of my kind of exercises I do from time to time. I never thought about photographing a rose, nor did I, upon thinking about it, think that I wanted to, but that sort of negativity associated with it made me think, "Okay, I should probably do it as an exercise anyway." And then when I did it, I kind of liked it.

No photograph was ever sold. There was a token called Rose, or Forever Rose, and that token represents my picture. That token is a proxy for my picture. The same way that my photograph is a proxy for the real rose, this is a proxy of a proxy. So no photograph was sold, okay? It was a single ERC20 token that was divisible to one decimal place, in other words, ten parts. So it's ten people owning a fraction of the single token. And those tokens cannot be divisible any more because the contract says they can only be divisible by one decimal place.

After hearing this, I was no longer sure if it made sense to include the Forever Rose in an article about photography. My takeaway was that the Forever Rose was about the conceptual act of selling ten shares of a single token and not the photograph. Kevin corrected me, saying:

Well, it is and it isn't. If you have seen the photo... first off, anyone can just download it onto their phone or their computer and look at it. It's there for them to see it if they want to. If you you've seen it once, maybe you never want to see it again, maybe it left an impression, maybe it didn't. I think it's very healthy to back off the materialism of having to posses a physical artwork -- not for everything, but at some point it is rather refreshing and healthy to untether yourself from the physical.

Kevin pointed out that he was ultimately driven to participate in the Forever Rose project as it was an opportunity to raise money for charity. The $1m went to the Coder Dojo. Coder Dojo is a charity which teaches children around the world to learn to code.

While I like the photo of the rose just fine, I personally think the Forever Rose project is best enjoyed as a conceptual exercise. I had a great conversation with Kevin that went much deeper than the excerpt above and plan on publishing it in full. He was extremely generous with his time, and I really enjoyed his line of thinking. And in case you are wondering, Kevin still has the photograph and is considering whether he may want to sell that at some point.

Why Would a Photographer be Interested in the Blockchain?

Kate Shifman

Fog Gowanis

2014

Fine art photographer Kate Shifman reached out to me after reading one of my early articles on art and the blockchain. I liked her work, so rather than speculate on what is drawing photographers to the blockchain, I asked Kate what got her interested in blockchain and what she hoped to get out of it:

As a photographer, the blockchain is compelling to me for the opportunities it presents in both art and commerce. The most direct benefit is, of course, access to the vast and open marketplace not subject to the artificial limitations imposed by the art world establishment and the ability for the work to be authenticated and editioned.

The idea of the artist continuing to own a part of their work post-sale is a very interesting one, as it empowers the artist like never before while shifting the bulk of the responsibility for the lifetime value of the work from the dealer to the artist. I can't tell yet whether this is a way to liberate talent or create a "hit-making machine."

In a bigger sense, blockchain enables communities to appear and thrive organically, unsanctioned by authority. This is uncharted territory for us as a society, but one thing is clear to me: as technology and politics converge in what seems to be the perfect storm of worldwide dissent and rejection of centralized power, the individual and the community rise to the forefront of social consciousness. In this new framework, photographic and other artifacts can be created and live simultaneously in the physical and digital realms being co-created/modified/sourced by engaged communities on the blockchain, presenting never-before imagined opportunities for creation, collaboration, and distribution.

Others may have different reasons, but I think Kate's response does an excellent job of elegantly encapsulating the reasons blockchain is capturing the interest and imaginations of the photographers and artists I have spoken with.

Will People Still Buy Physical Photographic Prints?

Men on a Rooftop

René Burri, taken in San Paulo, Bra1960

Yes. In fact, we may see even more people collecting physical fine art photography prints than ever before. However, how they collect and what "ownership" means might change as a direct result of the blockchain.

Switzerland-based company Tend provide "co-ownership of precious, special objects and unique assets," including photographs. They have recently negotiated a contract to sell several photographs by internationally renowned Magnum photographer René Burri.

I recently spoke with Tend CEO Marco Abele about Tend's model. Marco explained:

My thinking was for Tend, can we not democratize the luxury goods investment world and give it access to a much broader audience? Especially the emerging young generation who's aspiring to have something more meaningful and emotional to invest in. That's how Tend started, and we found a model where we combine having co-ownership in a certain beautiful, precious investment, but also allowing you to experience it from time to time.

It combines the two worlds of investing into something purposeful and at the same time leting you experience a bit joy out of it pretty early.

That all is managed on a new platform, which is our technology that leverages blockchain technology in the sense of personal ownership, of transparency provided by the transaction history. Of course, there is also the decentralization and lack of counter-party risk that comes along with the long-standing proposition of the blockchain. Combining the thinking of shared economy with the blockchain is, in my opinion, a very big use case. Tokenizing the assets of the world is just matching so much with what blockchain stands for and for what the consumer is driving at in terms of sharing the resources in the world.

Marco believes that the concept of ownership should be updated for a new generation of collectors who care more about experiences than in owning things (I agree with him). However, he does not believe that physical prints should always go away in the new model, as living with a beautiful print is an important part of experiencing art. So instead, Tend allows for small groups (five to 25) who are geographically co-located to invest in luxury items as a group.

For their first series, they are making four physical prints by the artist René Burri available. Tend's chief customer officer Caroline Bauden explained to me that the choice of the Swiss photographer René Burri was highly intentional.

We didn't take Burri completely by chance. Part of the reasoning was that he was Swiss and because he had recently passed away. That was in keeping with our brand and our client identity. And we have been lucky to find in our network an art advisor in Zurich, and she introduced me to the art of this photographer. I feel that it would be something very interesting for our customers.

It is important to note that tokenizing physical assets and digital assets are two entirely different things. In this case, there are four physical prints being sold to a group of co-owners that Tend plans to cap at about five people. As Caroline explained it to me, "If you will open that to five hundred people, you have no chance to have a decent and really interesting experience for the co-owners."

Summary and Conclusion

In this article we covered several topics including:

Summary of reasons photography is an ideal art form for blockchain

The digitization and explosive growth of photography in the last 20 years

The difference between centralized and decentralized solutions

Comparison of physically rare editions vs. digitally rare editions

Why a photographers would even be interested in the blockchain

New ways of collecting and tokenizing physical photographic prints

What are some areas we may see additional innovation with blockchain and photography in the future? Perhaps some of the most exciting advances for photography on the blockchain will come from the blockchain side and not the photography side. Smart contracts include legal rules and repercussions for contractual agreements, but also enforce those rules and repercussions automatically with coding and cryptography.

I spoke with Cynthia Gayton, who is perfectly positioned to discuss smart contracts in relation to art. Cynthia is an attorney who teaches IP law to engineers, and once owned an art gallery. She is also a long-time blockchain enthusiast and cohosts the podcast Art on The Block Chain. Cynthia is surprised that we have not seen more innovation around smart contracts. In her words:

The contract terms haven't changed. They are pulling the old models from the industrial era into this new environment. The sky is the limit with what you can draft with a smart contract. Why are people using ideas that are obviously not beneficial to artists? This is what perplexes me. You could be doing something completely different. You could create a joint contract with an artist and the developer meeting together as equals instead of the developer dictating what the artist is doing. That is my issue with it. It's like when people write fiction. You could be writing anything, but instead you recreate facts instead of making everything brand new. Part of me thinks it is a rush to production, often with the sole goal of making money.

Part of the appeal of blockchain to me is the variety of skills required to leverage its full potential. Luckily, people like Cynthia who have legal, technical, and artistic knowledge are actively engaged and can help us to fully explore the expansive potential of blockchain for photography and all of art.

Have an interesting use of blockchain for photography that you think I should know about? Hit me up at jason@artnome.com.