Yesterday was Mark Rothko’s birthday, and I wanted to celebrate by sharing some stats from the Artnome database on one of my favorite artists.

Born on September 26th, 1903, Mark Rothko would be 115 years old today. Though he tragically cut his own life short at the age of 63, Rothko left us 836 known paintings that were created over a 46-year span. This translates to roughly 18 paintings a year, more than one per month. Of course, no artists’ production is a constant; there are fat years and lean years of production.

Rothko began transitioning from his more surrealist-style paintings into his more abstract signature “multiform” style in 1947. That same year would also be his most productive, yielding 43 paintings, more than double his annual average production. As with most artists in our database, his leanest years came at the very beginning and very end of his career, producing just two or three works per year in those years.

Mark Rothko Painted 23.3k sq. ft. of Paintings

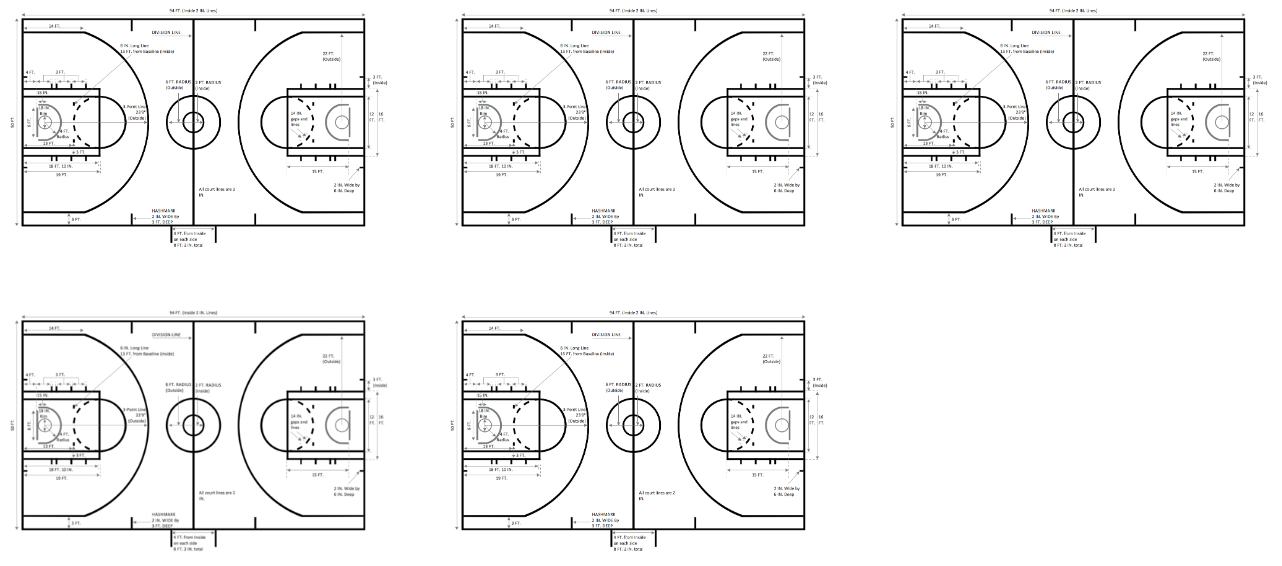

Rothko painted a total of 23,342 square feet, or approximately the surface area of five regulation NBA basketball courts combined.

Though he moved to smaller works on paper on doctor’s orders when his health was beginning to fail later in life, Rothko was known for painting vast and immersive canvases throughout most of his career. We can see how the size of his canvas evolved over his career in the graphs below. The spikes for 1965 and 1966 coincide with the work he created for the Rothko Chapel.

Mark Rothko Outliers

Mark Rothko, Untitled (Rust, Blacks on Plum), 1962, oil on canvas, 60 x 57 in

The average size of a Rothko painting is 60.4” x 52.6”. And while every Rothko is unique, the most “average” Rothko, by dimensions, would be his 1962 painting Untitled (Rust, Blacks on Plum), which measures in at 60 x 57 inches.

I had the awesome pleasure of visiting Rothko’s widest single canvas, Panel Two from the Harvard Murals painted in 1962 which stands 267.3 x 458.8 cm at the Harvard Art Museum in 2015.

Mark Rothko, Panel Two from the Harvard Murals, 1962 tempera on canvas, 267.3 x 458.8 cm

The Harvard Murals were damaged and had been kept in storage until a brilliant team of conservationists developed a technique for projecting light onto the canvases so that Rothko lovers like me could see them in something close to their original glory. While some criticized the approach, for an art nerd like me, the intersection of art and tech on this project was near nirvana. (Coincidentally, the Harvard Fogg also has the tallest painting by Jackson Pollock. I am a member and work a block away - the museum is art nerd heaven, and I’m lucky to have such great access.)

Rothko’s tallest painting is the center panel of the North Wall Apse Triptych in the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas (on my bucket list). At 457.8 x 267.3 cm, it is listed as just 0.6 cm taller than the other panels.

Mark Rothko, Rothko Chapel, 1964-1967 Houston Texas

The smallest painting by Rothko listed in his official catalogue raisonne is actually a tie between two paintings: Untitled (still life with mallet, scissors and two gloves), 1938/’39, a mere 7.5 x 12.6 square cm, and Untitled (still life with radio), 1938. Both are oil and gesso on board. I was able to locate the Untitled (still life with mallet, scissors and two gloves), which resides in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., but could not locate an image of Untitled (still life with radio).

Mark Rothko, Untitled (still life with mallet, scissors and two gloves), 1938/’39, 7.5 x 12.6 cm

I’m often asked why I spend so much time and money gathering data for the Artnome database. For many, quantifying art seems pointless and potentially disruptive to the real purpose of simply enjoying art. To these people I explain that when I love something, I simply want to know as much about it as possible. Without the context of a basic macro view of the complete works of an artist, how do we know what large, small, wide, or even rare really is?

I also believe that given the prices being paid for paintings by artists like Mark Rothko, collectors and institutions will soon come around to demanding the same level of data on art as they have in all other areas of their lives. Rothko’s most expensive work to date is his Violet, Green and Red, 1951, painting which reportedly sold in $186M in 2014 through private sale. By blending auction data with data on the complete works, we can go beyond a short and fun analysis like the one in this post and look at what factors actually make a work like Violet, Green and Red unique and provide valuable insight to collectors.

Mark Rothko, No. 6 (Violet, Green and Red), 1951, oil on Canvas, 230 x 137 cm

If you would like to learn more about my database project, you can read more in this Artnome article or read Oliver Roeder’s excellent article in FiveThirtyEight which is, in my opinion, still the best place to get the background on my moonshot Artnome database project. As always, you can reach me at jason@artnome.com with any questions or suggestions.

For fun, I am concluding with this stealthy photo I took of a museum goer “twinning” with a Rothko at the Boston MFA show last November. If you haven’t already - don’t forget to subscribe to the Artnome newsletter!

Stealth photo I took of a man “twinning” with Mark Rothko’s x at The Museum of Fine Art in Boston