The tools for using artificial intelligence and machine learning to create art are currently complex enough that only a small number of highly technical people have mastered them. This came up on a recent panel I moderated on AI art at CADAF (Contemporary And Digital Art Fair) in NYC.

Specifically, I asked the panel if you “need a degree from MIT and to be a white guy over 40” to create art with artificial intelligence and machine learning, as many of the panels I attend on AI art have seemed particularly homogenous. The question was, of course, somewhat rhetorical, as I am well aware of great work being done with AI by non-white and non-male artists. But the balance for panels so far does seem to skew in that direction.

One way to increase the diversity in art created with artificial intelligence is to continue to invest in making code open source. However, not everyone can or will learn to code, but with the development of new tools like Runway ML, you may not have to.

I have been following Runway ML since May, 2018, when I read cofounder Cristóbal Valenzuela’s excellent essay “Machine Learning En Plein Air: Building Accessible Tools for Artists.” In the essay, Valenzuela compares the current barriers for artists in using AI to the barriers that would-be artists faced in creating their own pigments and paints prior to the invention of the collapsable paint tube.

Valenzuela points out that many credit the portability of the paint tube with making it practical for artists to paint plein air (outdoors) in oils. The great painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir even credited the invention of the paint tube with triggering “Impressionism” and assisting to usher in modern art at large.

“Without colors in tubes, there would be no Cézanne, no Monet, no Pissarro, and no Impressionism.” - Renoir

Like Valenzuela, I believe the democratization of artificial intelligence for artists and designers will drive a revolution in aesthetics. Specifically, I believe we will enter an era of mass appropriation and radical remixing of visual materials like we have never seen before.

In this blog post, I argue that it is the nature of AI and ML as art making tools that they will require an enormous amount of visual material as fuel to train their models. It is also the nature of AI and ML that the resulting artworks are essentially radical remixes of the work that is used to fuel them.

We can already see this trend in “appropriation” and “remixing” of visual material in the work of accomplished AI artists. Mario Klingemann’s Lumen-award-winning piece The Butcher’s Son for example, was trained on a large number of pornographic images.

The Butcher’s Son, Mario Klingemann, 2018

Klingemann explained in an interview with Fast Company in 2018 that he chose to train on pornography because it is “one reliable and abundant source of data that shows people with their entire body.” He then added that sports would have been another source, but he is not that into sports.

Similarly, AI artist Robbie Barrat has famously trained models on famous portrait paintings of nudes and even trained a Pix2Pix model on the complete Balenciaga online fashion catalog.

AI Fashion, Robbie Barrat, 2018

AI Fashion, Robbie Barrat, 2018

Barrat’s most recent work remixes appropriated imagery in a slightly different way. For his series of artworks Corrections, Barrat starts with images of classical paintings by old masters and applies a custom “flesh finding” algorithm.

Saturn Devouring His Son (After Peter Paul Reubens), Robbie Barrat, 2019

Barrat shared the genesis behind his Corrections in a recent interview I did with him for the catalog for the Automat und Mensch exhibition.

When I was in France in Ronan’s studio [French painter Ronan Barrot], I saw that he had a scene that he was not satisfied with, and he covered over the parts that he didn’t like with bright orange paint. And then he filled those parts back in. I thought that was really interesting, and he called those “corrections.” And during our confrontation, he also corrected a lot of my AI skulls. I was really fascinated with the painting over the parts you don’t like and redoing it. I thought that was a really cool way of doing it.

So I basically am teaching the neural networks to do pretty much the same thing. I’m using Pix2Pix, and it is basically trying to learn the transformation from a patch of a painting with the center part missing back to the full patch of the painting. If you look up “neural inpainting,” you’ll find this.

While Barrat and Klingemann both typically appropriate and remix from large public data sets of images, other AI artists like Helena Sarin, David Young, and Anna Ridler choose to train their models based on their own photography and hand-drawn/painted artwork. Anna Ridler, for example, shot a large corpus of tulip photos to train her Mosaic Virus video piece which draws “historical parallels from ‘tulip-mania’ that swept across Netherlands/Europe in the 1630s to the speculation currently ongoing around crypto-currencies.”

Anna Ridler, tulip photos used to train Mosaic Virus

Even when training models using their own materials and avoiding appropriation, the process of using neural networks to create art is ultimately still one of remixing.

Some artists might argue with me here and point out that neural nets are creating entirely new works, not remixing old ones. But there is no question that the visual materials that artists curate and train the models with have a huge impact on the end results. It is this process, in particular, that I am referring to as “radical remixing” - radical in that I agree it is far different from traditional visual remixing through techniques like collage or even sampling in music.

Once you see the pattern of appropriation and remixing present in the work of AI art pioneers, it becomes easier to imagine what this might look like once the tools become more accessible to artists and designers at large. I believe it will start a new aesthetic revolution that will change the world through art, advertising, and political propaganda - all heavily based on mass appropriation and radical remixing of visual imagery.

How close are we to the democratization of AI for artists? I decided to be the guinea pig and jump in to Runway ML and see how challenging it would be for me to play with these tools to create new images.

Runway ML - Artificial Intelligence for Augmented Creativity

I have wanted to explore Runway ML and write an article about it for many months now, but I though it would take a lot of time to learn how to use it. I was wrong. In less than an hour I was up and running, creating multiple projects. Pretty quickly I became convinced Runway ML is onto something huge here and will be the Photoshop for the next generation of artists and designers.

Before I share more about the projects that I built using Runway ML, I should explain a bit about how the tool is constructed at a high level. The team at Runway ML does not necessarily write the actual algorithms for artists and designers to use. Instead, they have designed a framework to make it possible to integrate the latest algorithms from academic research into an intuitive interface that does not require programming skills on the part of the artist or designer.

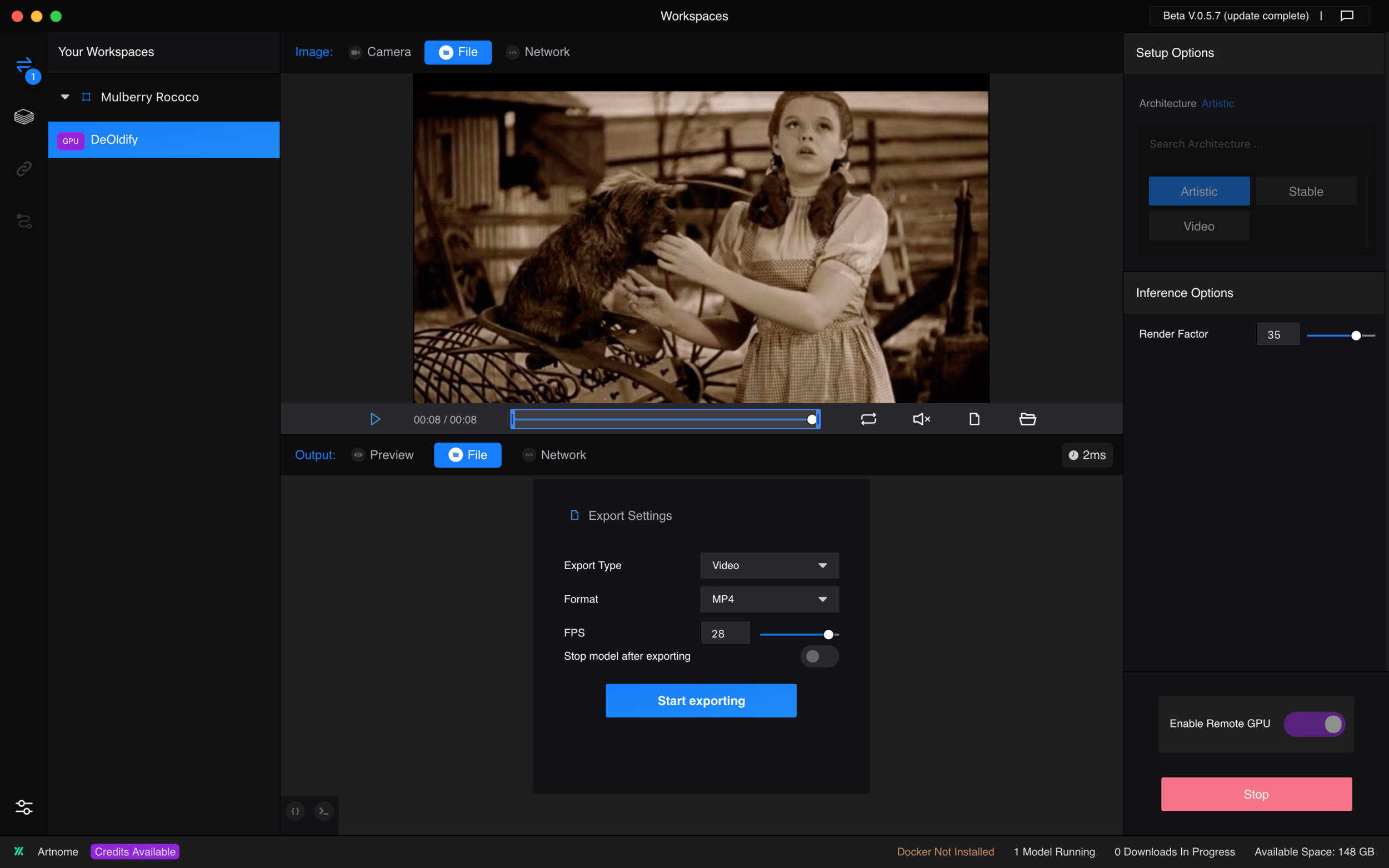

For example, the first thing I tried in Runway ML was to colorize an early black-and-white scene from The Wizard of Oz. Runway ML has added Jason Antic’s excellent DeOldify model into their interface for color correction. It was super easy: I just loaded the clip in Runway ML and applied the filter. I didn’t even need to read the instructions or documentation.

The whole process took less than 15 minutes, and most of that was processing time. The interface was intuitive enough that I did could just use it.

With some newfound confidence that I could use the tools in Runway ML, I began to explore and run other models. I started thinking more about what visual materials I would want to play with. This is just the nature of Runway ML - you think, ‘I’ve got access to these cool models - what visual material can I apply them to?’ The tools in Runway ML simply do not do much until you feed them visual material; hence, my belief that we are hurtling towards an era of mass appropriation and radical remixing spurred by the inevitable democratization and adoption of these new tools.

My favorite visual materials are the artworks from 20th century art. Unfortunately, all the work created since 1923 (the work I love most) is still under copyright. With Robbie Barrat’s Corrections in mind, I wondered if there was a way to identify the visually important parts of these artworks, not to correct them, as with Barrat’s work, but to surgically remove their “hearts,” leaving only the parts that are unimportant enough to be legally shared with the masses as new works of parody.

Runway ML had exactly the model I was looking for. A model called “Visual-Importance” trained “neural networks on human clicks and importance annotations on hundreds of designs” to identify the “visually important” and “relevant” areas of images based on human perception. So I decided to run some copyrighted images from 20th century art through the model to identify the important parts of the images and then isolate and remove them.

I’m not a lawyer, but I remembered from my interview with Jessica Fjeld, assistant director at Harvard Cyber Law Clinic, that fair use of images is largely based on the “amount and substantiality” of the portion of the work you are pulling from. You are most likely to run into problems if you take the most memorable aspect, often referred to as the “heart” of the work. My entire process is based on using the most advanced technology we have at our disposal to surgically remove the “heart” and to remix the “visually unimportant” scraps into a new work of parody.

I started by running David Hockney’s wonderful Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), which recently sold for $90M at Christie’s last fall. The heat map below produced in Runway ML shows the most “important” and “relevant” areas of the painting highlighted in white.

I then took this image into Photoshop and ramped up the contrast to isolate the important areas from the less important areas in clear blocks of white on black.

I erased the “visually important” areas of the artwork, leaving only the irrelevant portions. I was actually really happy with these results and almost stopped there.

To go a step further in transforming the work to make it my own, I used Photoshop’s content-aware-fill plugin. The plugin uses an algorithm to fill in all the white spaces by using the remaining areas of the work, the areas that were deemed “visually unimportant” by the neural net in Runway ML.

Olive Synchronism (After Hockney), version 2, Jason Bailey, 2019

Though I love Hockney and the original painting, I believe my version is a new work which has an entirely different feel. I am quite fond of it. It has a vibe similar to Lewis Baltz, one of my favorite photographers who is known for finding beauty in desolation. The new version is most notably absent of the emotion, narrative, and price tag present in Hockney’s original painting.

I am, of course, not the first artist to create art from art. There is a long tradition of artists painting other artists’ paintings within their own painting. These paintings about paintings were especially popular in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Art Collection of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in Brussels, David Teniers the Younger, 1650

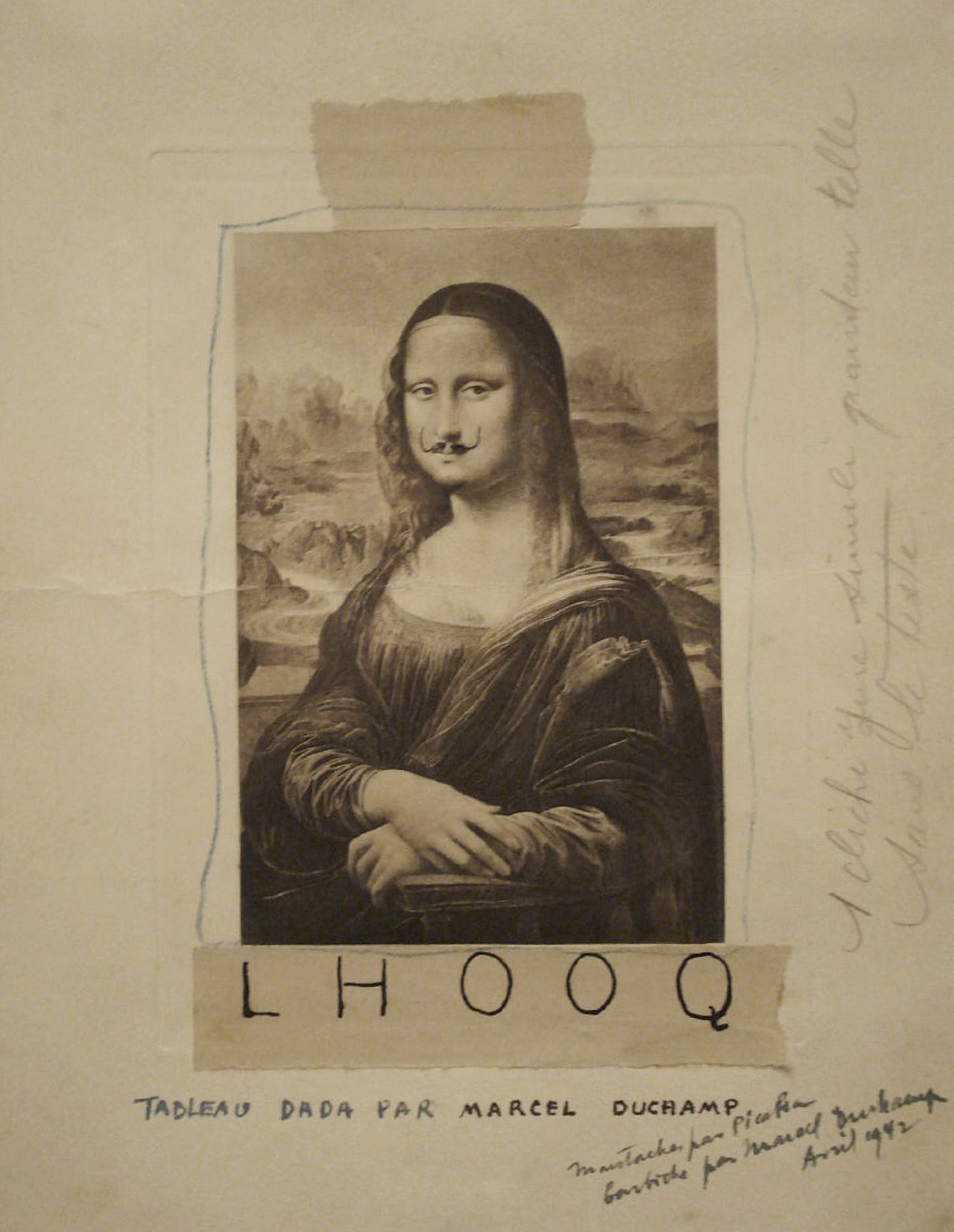

Marcel Duchamp famously painted a mustache onto Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in 1919 and named the work of parody L.H.O.O.Q., which spoken in French translates roughly to “she has a hot ass” in English. Duchamp considered the work a “rectified ready-made,” a new work transformed by his addition of facial hair and the new title.

L.H.O.O.Q., Marcel Duchamp, 1919

Artists have long used direct appropriation of visual materials as a core part of their work - AI is just a new tool with deep potential to take it to a another level. Collage was raised to an art form by Picasso and Braque in the 1920s, and other artists like Kurt Schwitters, Hanna Hoch, John Heartfield, Jess Collins, and Richard Hamilton, spent their careers mastering it.

Roy Lichtenstein’s entire body of work was based on appropriating images from comic strips. Lichtenstein would enlarge, isolate, and crop elements directly appropriated from pop culture to create new works of art. His first appropriated work was directly lifted from a comic strip of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck fishing. He titled the 1961 work Look Mickey.

I decided to extend the chain of appropriation and identify and remove the important elements from Lichtenstein’s appropriated work below.

Sketch for Nut Aestheticism (after Lichtenstein, after Disney), Jason Bailey - 2019

Nut Aestheticism (after Lichtenstein, after Disney), Jason Bailey - 2019

In this case I think I like my erased work better than my final version with the missing areas automatically filled in. The version with the white splotches would make a really cool graphic on a t-shirt.

Notably, I am also not the first artist to erase portions of another artist’s work and to claim that the results are a new work of my own authorship.

In 1953, artist Robert Rauschenberg asked himself if it was possible to create a new artwork completely from erasure (as I have). He started exploring this idea by erasing his own drawings. He felt that the result was not sufficiently creative, so he decided to ask William de Kooning, whom he looked up to as an artist, if he could erase one of his drawings, instead. After some hesitation, de Kooning gave Rauschenberg a drawing created with mixed media that he was fond of, but also knew would be a real challenge for Rauschenberg to erase.

Traces of ink and crayon on paper, with mat and hand-lettered label in ink, in gold-leafed frame

25 1/4 x 21 3/4 x 1/2 inches

(64.1 x 55.2 x 1.3 cm)

de Kooning chose well, and it took Rauschenberg two months to erase the piece. Rauschenberg finished the piece by putting it in a gilded frame and having his friend artist Jasper Johns add an inscription reading “drawing [with] traces of drawing media on paper with label and gilded frame.” The work now hangs in the SFMOMA.

Rauschenberg was also no stranger to appropriation. In 1979, he was sued by photographer Morton Beebe for including a photo Beebe had taken in 1971 of a cliff diver, which Rauschenberg used in his own piece titled Pull from 1974. In a letter responding to Beebe, Rauschenberg argued:

Dear Mr. Beebe,

I was surprised to read your reaction to the imagery I used in Pull, 1974. Having used collage in my work since 1949, I have never felt that I was infringing on anyone’s rights as I have consistently transformed these images sympathetically with the use of solvent transfer, collage and reversal as ingredients in the compositions which are dependent on reportage of current events and elements in our current environment hopefully to give the work the possibility of being reconsidered and viewed in a totally new concept.

I have received many letters from people expressing their happiness and pride in seeing their images incorporated and transformed in my work. In the past, mutual admiration has led to lasting friendships and, in some cases, have led directly to collaboration, as was the case with Cartier Bresson. I welcome the opportunity to meet you when you are next in New York City. I am traveling a great deal now and, if you would contact Charles Yoder, my curator, he will be able to tell you when a meeting can be arranged.

Wishing you continued success,

Sincerely

Robert Rauschenberg

Perhaps not surprisingly, Rauschenberg’s estate has been one of the more liberal estates when it comes to opening works under copyright for scholarly use and public consumption (partly why I felt it was okay to use the erased de Kooning drawing above in this post).

In homage to Rauschenberg as a great appropriator and master remixer of visual imagery, I ran his 1954 work Buffalo II, which recently sold for $89M at auction, through my visual neutering process.

Huckleberry Objectivity (after Rauschenberg), Jason Bailey - 2019

I love Rauschenberg, but I think I actually like my “visually unimportant” version even more than the original.

Rauschenberg passed away in 2008, but from what I know of him, I believe he would appreciate my posthumous collaboration in the spirit of his own visual remixing and appropriation.

Enthused by the results from processing Rauschenberg’s largely abstract Buffalo II, I was curious about how my process would handle a completely abstract work. Since de Kooning seemed okay with Rauschenberg’s erasure of his drawing, I figured he would not have minded if I ran his painting Interchange through my process, as well.

Persimmon Precisionism (after De Kooning), Jason Bailey - 2019

De Kooning’s Interchange is best known for reportedly selling for $300M in 2015. Mine is quite nice, as well - I don’t miss the heavier black lines. I feel like my version almost has a Diebenkorn feel to it.

Conclusion

Historically, when new tools for copying, manipulating, and multiplying existing images become available, we see an upsurge in appropriation and remix-based art. We saw this with Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, who co-opted screen printing for fine art and in photography with artists like Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince.

Series of people who do not actually exist created using GANs - https://www.thispersondoesnotexist.com/

With AI, we have tools that are sophisticated enough to generate endless convincing images of people who do not exist and to map our faces and our own physical movements using motion transfer onto people who do exist, as if they were our own personal puppets. Add to this the fact that we are making these powerful tools available to the most tech savvy generation ever, one that “gets” artistic appropriation as seen in their love KAWs, and you have the makings of an artistic revolution.

Think of Photoshop’s impact on visual culture for everything from politics to pop culture over the last 20 years. If you multiply that by ten, you will get my approximation of the impact accessible tools for using AI could have on art and design in the next 20 years.