“The force of art lies in its immediate influence on human psychology and in its active contagiousness.” - Naum Gabo

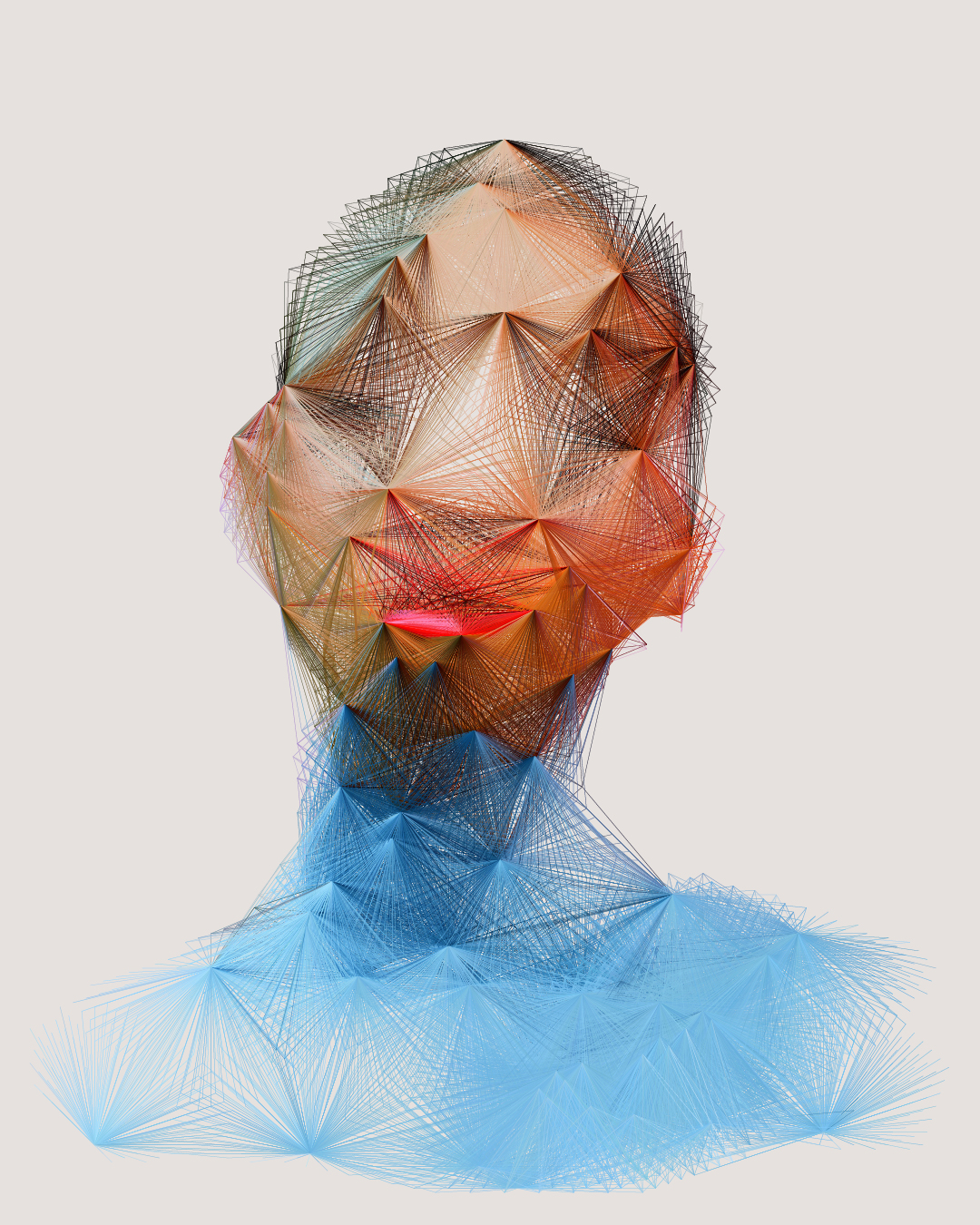

Espen Kluge, ash when he arrives, every time - 2019

I have a deep and well-documented love for generative art. I’ve gone as far as saying that generative art is the most important art of our generation, as it best reflects the digital transformation that so deeply separates us from all that came before us.

However, the nature of generating art with code typically leads to results that are highly geometric, abstract, and non-representational. And my first true love in art will always be portraiture.

So when I discovered the arresting generative portraiture of Norwegian artist Espen Kluge several weeks ago, I was immediately taken in.

Espen Kluge, makes great choices while angry - 2019

I love portraiture because evolution has trained us to read the nuance of human facial expression with a higher degree of sensitivity than any other visual input. From finding a mate to sensing a foe, our ability to read the subtle expressions of others is critical to navigating many of the most important and meaningful aspects of life.

Our supercharged sensitivity to these facial signals creates a playground for portrait artists who can combine, bend, exaggerate, and break the signals to manipulate us and make us feel with heightened intensity.

Kluge does this masterfully in his new series of portraits titled Alternatives which source and alter photographic portraits to tell stories alternative to their origins.

Espen Kluge, superclear when I say it’s risky business - 2019

Though they are composed of two-dimensional vectors, Kluge’s portraits feel structural, almost architectural. They immediately reminded me of a blend of the dynamic sculptures of Russian constructivist Naum Gabo mixed with a hint of mid-century modern symmography (aka ‘70s string art).

Linear Construction No 2 Naum Gabo, 1950

1970s symmography string art

With twenty years’ experience working in digital media, if I see something beautiful and I can’t figure out how it was made, I feel deeply compelled to reach out to the artist.

I set up a call to speak with Espen Kluge about his work and caught him during a visit to Sweden to help his fiancee prepare her apartment for sale.

I was honestly a bit surprised to hear Kluge speak perfect English because I had assumed his deadpan titles like “makes great choices while angry“ and “cruise ships and police cars“ were in part a function of English not being his first language. He explained that he gets his titles by pulling snippets from the text associated with the source images he uses to create his portraits. He was a bit apologetic about this, and wondered aloud if he should spend more time on the titles. I assured him the titles added just the right amount of mystery and fun while avoiding the trap of becoming overly pretentious and serious.

Kluge shared that he grew up in Norway, where he still lives and works today. He earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts but then pivoted and studied composition in music for TV and film for his master’s degree.

Kluge’s music, like his portraits, is psychologically nuanced and exploratory. You can hear his soundtrack for the 2018 television show Who Killed Birgitte? on Spotify. I listened to it while writing this post and highly recommend it. It’s my new go-to music for writing.

I wanted to know how someone who went to school for visual art and then film scoring got into programming and code-based art.

Kluge explained that while studying for his master’s degree, he had developed an obsession for an idea that he could not shake:

What if there was a keyboard that had keys that lit up not based on anything that was pre-composed, but in real time, based on your own improvisation?

Kluge became so obsessed with this idea that he taught himself how to code from scratch at the age of 27 so he could start his own company and build his invention.

Drawing from the patent awarded to Kluge for his improvisational keyboard

Though his improvisational keyboard was programmed in Objective C, Kluge often took breaks to create more visual projects in Processing and eventually JavaScript. One such project was based on the idea of making an interactive logo for his website. The logo was a portrait, and Kluge wanted it to take on the colors of the pages it appeared on and to “do something interactive,” as he described it.

Though he failed at his initial objective, Kluge ended up creating a really cool piece of code that took in photographs as input and then output what would become the initial foundations for his colorful vector-based portraiture series.

Original logo project image that spawned Espen Kluge’s current portrait series

At the time, busy getting his master’s degree and building his company, Kluge decided to put the logo project on the back burner, where it remained for many years. It was only this past January that he rediscovered the project and began refining the code again.

I asked Kluge how his code works. He explained that the code loops through all the pixels in a raster image and chooses some at semi-random, then engages those pixels by putting lines between them. He added that he is able to adjust five or six variables to do things like focusing in on one color more than another.

Espen Kluge, cruise ships and police cars - 2019

Kluge admits the code is not super clean, but through his manipulations, he has built his own tool for making art. The results speak for themselves.

Kluge would like to get to a spot with the project where he can do less and less work on the images so that it becomes more generative. But for now they require a lot of creative intervention to yield the results he is happiest with.

Espen Kluge, they don't have this for humans - 2019

For now, each image can take Kluge from ten minutes to an hour to create. The process requires that he source several input images, as some just come out “flat and boring” and he is not always sure why. But over time, his intuition has improved as to what makes for better input images. For example, photos with distinct facial expressions, open mouths, good lighting, rich skin tones, etc., seem to work best. He really likes photos of dancers with makeup, as they tend to have strong or exaggerated features.

Kluge often takes the base photo into Photoshop and changes the colors and gradients as a middle stage based on what he knows will work well with the algorithm. You can see from the before and after images below that the output image often bears very little resemblance to the source image he starts with.

starting point (thinking outside the ocasahedron)

thinking outside the icosahedron

Kluge has built an assembly line of code variations he likes into the software tool CodePen so that he can rapidly try out different configurations on his source images. He claims to have “about 100 saved combinations.” He will typically try an image across 20 or so of his CodePen variations, searching for the best possible output and making further changes to the code when necessary.

I love Kluge’s description of his organic coding process for creating art. It flies in the face of the popular misconception that programming art is somehow a linear process, when in actuality, it is almost always circuitous.

When I asked Kluge if he is still surprised by the outputs he is getting, he replied:

Oh, yeah, I wouldn’t have the motivation to do this at all if I wasn’t surprised every time. It’s a pleasure every time I get close to something I like. I don’t have a good drawing hand. This is something I use to be my drawing hand. Sometimes the lines and shapes can be really beautiful, and I don’t think I could calculate that. It’s impossible for me to have these things in my head before I start. I would like to think this is true for all generative artists. It is a very playful process.

Espen Kludge, any individual - 2019

Because Kluge’s portraits feel so three dimensional to me, I asked him if he had played with adding a Z dimension to the pixels. He shared that he had considered importing them into Houdini (a 3D software package), but wanted to keep them as pure code since that is how they were born. He added that he may explore doing some work with them in 3D using Python.

I was also curious if he had explored making them interactive, animated, or motion based. Kluge explained that he fears that adding animation to the portraits would demystify them for him and could make it something he feels it shouldn’t be.

Espen Kluge, ladyfriend - 2019

The look of the portraits varies broadly across the series based largely on the quantity and density of the lines. Some of the more dense portraits look almost like photographs while other more sparse portraits look more geometric and abstract.

Not that it drives his decisions or his process, but Kluge did share that the ones that get the most likes on social media tend to be somewhere in the middle.

Espen Kluge, more extroverted than you - 2019

Personally I think Kluge’s choice to share works that range in line density is itself important. The sparse ones help me appreciate the dense ones more and vice versa. It is an exercise in contrast, and the work benefits from the display of the full spectrum.

In fact, I think the shift toward and away from abstraction through variation in line density is a big part of what makes Kluge’s portraits feel so fresh and emotive, especially when compared to traditional generative art which can often feel cold, geometric, and repetitive.

Espen Kluge, 100 atoms in my favor - 2019

An artist’s artist, Kluge is candid and open about his process, one which is beautifully honest and imperfect. When I asked him about the similarities between programming with Java and film scoring, he shared:

Both are programming languages, Java script and musical notation. But I have never been very good or very intuitive with code or notation - I have always been very chaotic with both programming and notation. I took longer than most students to get there with music notation. But sometimes you take the longer road and you get your own very unique experience with things, which I think results in something very cool and creative.

As someone who also spent their life breaking things and doing things the “wrong” way, I couldn’t agree with Kluge more. I also agree that the uniqueness of his work is likely a direct result of his struggles and unique journey.

Kluge, his music, and his art are truly fantastic treasures. It is artists like Espen Kluge who keep me excited about discovering new work and sharing it through my writing on Artnome. Additionally, in my new capacity as senior curator for Kate Vass Galerie, I have the added pleasure of making introductions for artists like Kluge to help further raise his profile and identify a network of collectors and appreciators for his work. Thanks to Espen and Kate, the work I have curated for this article is also now available to Artnome readers and collectors of digital art. You can find both digital and printed works at the Kate Vass website.