I recently read that the average millennial will take an astronomical 25,000 selfies in their lifetime — almost one per day. This got me thinking about the history of selfies. Before the invention of the camera, artists were the only ones capable of making selfies (I know, what a tragedy, right?). So in a weird way, you could argue Rembrandt — known for painting an enormous number of self-portraits — was the Paris Hilton of his day. Sound crazy? It’s not.

Self-portrait in a hat with white feathers, Rembrandt, 1635

Portrait in a hat with pink feathers, Paris Hilton, 2018

Though the number is somewhat contentious, Rembrandt was known to have created close to 100 self-portraits (over 40 of them as paintings). That may not sound like much by today’s selfie standards, but it’s huge when compared to the painters of his day — especially when you consider that it accounts for 10% of his total artistic output. Think about it: he is a painter by trade, and 10% of his time on the job was spent making paintings of himself. If that’s not some Paris Hilton-level selfie action, then I don’t know what is.

The Old Masters Loved Showing Their Bling

Self-Portrait with a Sunflower, Anthony van Dyck, 1663 (note the flexing of the bling he received from his patron, the English monarch Charles I)

Maybe you are thinking, “Jason, Rembrandt is the greatest painter of all time. Surely he was motivated by something more noble than the vanity that motivates today’s selfie-snapping celebrities.” Well, actually, not so much. Consider this: old master portrait artists were often given gold necklaces from their wealthy patrons. This became such a big deal that the painter Titian decided to bling out his selfies by including the gold chains he received from his patron, the Emperor Charles V. It kicked off a fad among portrait artists including Van Dyck, Vasari, Reubens, Bandinelli, and others.

Self-Portrait, Titian, 1546 (wearing the golden chain that was given to him by the Emperor Charles V in 1533)

Self-Portrait, Baccio Bandinelli, 1530 (wearing a gold chain with a pendant bearing the symbol of the chivalric Order of St. James)

Not unlike today’s hip hop artists, these chains were a status symbol — they showed that an artist had “arrived” and was at the top of their game. Unfortunately, Rembrandt had no wealthy patrons when he was first starting out. Undeterred, he decided to “fake it till he made it” and painted imaginary gold chains on his self-portraits to suggest that he had a higher status and more power than he actually did. Talk about doctoring a selfie for purposes of vanity and status.

Self-Portrait with Beret, Gold Chain, and Medal, Rembrandt, 1640

Jay-Z: Portrait with Ball Cap, Gold Chains, and Brooch

The Dutch Love Their Selfies

Selfie with Van Gogh’s 1888 Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin (on a research visit to Harvard Art Museum)

“They say—and I am willing to believe it—that it is difficult to know yourself—but it isn’t easy to paint yourself, either.” - Vincent van Gogh

In terms of selfies, Van Gogh was not far behind Rembrandt, having painted 35 self-portraits in just one short decade of activity. That is roughly 4.2% of his total output and more than three self-portraits a year!

Van Gogh believed that painting could be reinvented through portraiture and fantasized about building a colony of artists working together. He also knew that Japanese wood block printers often exchanged prints among each other and encouraged his besties Gauguin and Bernard to exchange self-portraits with him.

As Van Gogh wrote:

It clearly proves that they [Japanese wood block printers] liked one another and stuck together, and that there was a certain harmony among them [. . .] The more we resemble them in that respect, the better it will be for us.

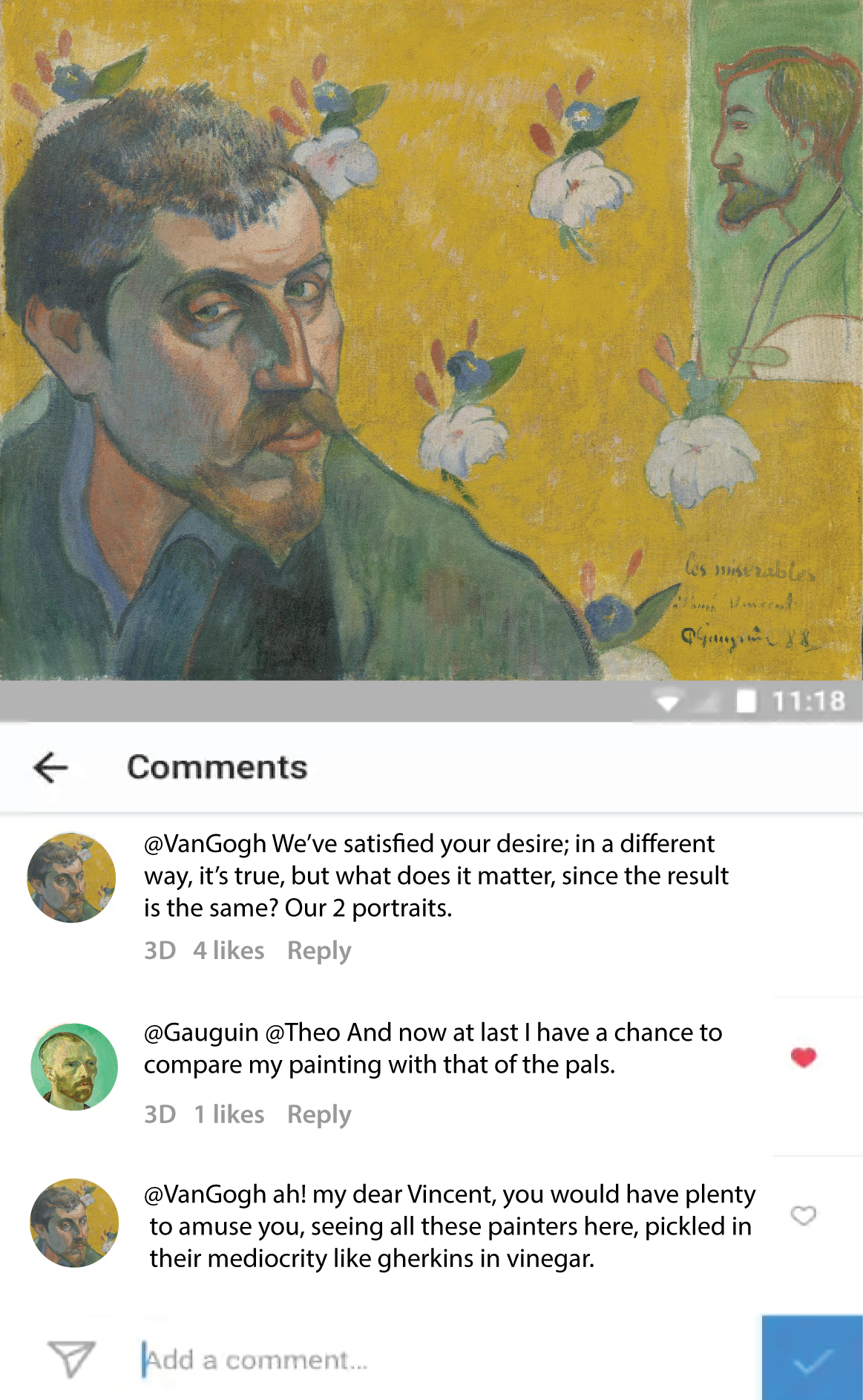

Van Gogh had essentially come up with an old-school social network where people could share and comment on each other’s selfies, not unlike Instagram or Snapchat. He wrote to his brother Theo sharing his thoughts on the self-portraits he received from Gauguin and Emile Bernard. Here is what Van Gogh’s comments would have looked like in Instagram (using actual quotes from correspondence between the artists).

Sadly, Van Gogh and Gauguin’s friendship famously soured, and Gauguin sold the portrait Van Gogh painted for him for about three hundred francs after making a few restorations.

Van Gogh’s portraits function like a visual diary. While his early works do not feature gold chains, they are painted in a dark Rembradt-esque palette and feature conservative clothing and a pipe, suggesting Van Gogh may still have been at least a little preoccupied with keeping up appearances.

Self-Portrait with Dark Felt Hat, Vincent Van Gogh, Paris, 1886

Self-Portrait with Pipe, Vincent Van Gogh, Paris, 1886

Self-Portrait, Vincent Van Gogh, Paris, 1886

By 1887 (just one year later), we see Van Gogh rapidly exploring self-portraits in the style of other artists, including influences from Impressionism, Pointallism, and Japanese woodblock prints. I believe we are also seeing a shift from portraits focused on external appearance towards portraits capturing his own psychological inner life.

Self-Portrait, Vincent Van Gogh, Paris, 1887

Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, Vincent van Gogh, Arles, 1889

Self-Portrait, Vincent van Gogh, Saint-Rémy, 1889

Averaging Rembrandt and Van Gogh Self-Portraits

It dawned on us that with so many selfies, Rembrandt’s and Van Gogh’s self-portraits comprised a pretty cool data set. After brainstorming with Artnome data scientist Kyle Waters, we decided it would be cool to create “average” self-portraits of each artist by combining their paintings into a single image. Kyle settled on using a similar approach to the technique he employed in averaging Van Gogh’s paintings to show why Van Gogh changed his color palette.

We started by importing all the self-portrait images for Rembrandt and Van Gogh from the Artnome database and set them all to be the same 400 x 400 pixels in dimension. I know, kind of a sin to change the aspect ratios of famous paintings, but this made it easier for us to "add" each image together, i.e., taking the red value of the top left pixel in Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and adding it with the red value from the top left pixel of Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin, and so on.

We then calculated the simple arithmetic average by dividing out the sum of pixels by the total number of paintings.

We were pretty psyched with the results. You can check them out below.

The average Rembrandt self-portrait

The average Van Gogh self-portrait

While there is a lack of detail, I actually love the results. You can definitely make out which is Rembrandt and which is Van Gogh. Rembrandt’s composite features an earthy brown color palette, while Van Gogh’s yellows and blues average a greenish hue, with patches of orangey-red where his hair and beard were most commonly depicted. It is also clear from the composites that Rembrandt preferred to paint himself looking to our right, whereas Van Gogh most often looks to our left.

We thought the effect was pretty cool, so tried it on a few other thematic subcategories, including Van Gogh’s portraits of Madame Ginoux and his sunflowers, respectively, creating an average-based image for each.

Visual average of every portrait of Madame Ginoux by Van Gogh

Visual average of the sunflower paintings by Van Gogh

As with the self-portraits, these were visually interesting, as you can still make out some of the features and shapes without one clear painting dominating.

Conclusion

Next time someone gives you a hard time for spending 15 minutes fussing with filters on your selfie, remind them that Rembrandt spent a full 10% of his career perfecting selfies. Who knows? Maybe there is even a market for an “old masters” app that lets people add gold chains to their selfies.

As always, thanks for reading. As we mentioned, this was inspired by Kyle Waters’ excellent work in averaging Van Gogh’s paintings for our post about the shifts in his color palette. We have a third post in the series that will focus on establishing “the average” Van Gogh work using several different techniques. Sign up for our newsletter and we’ll be sure to alert you when it goes live.

If you have questions or suggestions you can always reach me on Twitter at @artnome or email me at jason@artnome.com.