Feel free to continue reading our 2019 predictions but please note that we have also recently published our 2020 art market predictions.

I’m a little late on my art market predictions this year, but I had too much fun with my 2018 art market predictions to keep my crystal ball in the closet. This year, I go deep on two trends that I think will dramatically transform the art market, not only in 2019, but for the next decade: first, increased diversity/inclusion in the art world, and second, the digital transformation of art.

I believe we are on a massive collision course between populations that are becoming increasingly diverse and an art history and art world that is still very white and very male.

Many have told me that nothing changes fast in the conservative art world. However, I am predicting nothing short of a “Moore’s Law” of diversity in art. I believe 2019 will bring double the protests and market shift towards equality from what we saw in 2018, and this doubling will continue annually until we reach visible signs of parity. I theorize that continued pressure on art museums will drive rapid cultural change which will then trickle down and transform the art market.

Equally radical, I believe rapidly evolving technology, specifically digitization, is shaping human lives faster and more dramatically than any other series of events in history. I predict that digital transformation of the art world will lead to the beginnings of the dematerialization of art (as is already happening with books and music). And I argue that rather than a rise in the commoditization of art, we are actually seeing the early beginnings of a move away from ownership by traditional definitions.

I predict that museums, galleries, and auction houses will realize improving diversity/inclusion and focusing on the rapidly shifting intersection of art + tech is the key formula for increasing interest, engagement, and participation in the arts.

The rest of this post dives into why I hold these two beliefs. I try to take a first-principles look at art and its function in society, including its use in museums and private collections. I then take a look at what I believe are two important macro trends — a strong push for diversity and inclusion, and the digital revolution — and make predictions around the impact of those trends on art, its value, and its function in society.

Museums Are Serving an Increasingly Diverse Population

According to the Brookings Institution, the U.S. population is projected to become “minority white” by 2045. Additionally, Europe’s population as a percentage of the global population has been shrinking, moving from 28% in 1913 to 12% in present day, and is predicted to be just 7% by 2050.

As minority groups increasingly move towards forming a collective majority in the U.S. and Europe, it becomes increasingly important for museums to evaluate their collections and hiring policies to make sure they reflect the public they serve. This includes not only diversity in race, but working towards correcting longstanding gender inequalities, as well. There are many signs that there is still a lot of work to be done on both fronts and increasing pressure to get it done faster.

Sadly, but not surprisingly, the art market reflects these same biases.

80% of the artists in NYC’s top galleries are white (and nearly 20% are Yale grads)

77.6% of artists in the U.S. making a living from their work are white

Only five women made the list of the top 100 artists by cumulative auction value between 2011-2016

There are no women in the top 0.03% of the auction market, where 41% of the profit is concentrated

Overall, 96.1% of artworks sold at auction are by male artists

Despite the art world being disproportionately white, we are seeing trends of increased engagement across all minority groups in attending U.S. museums and galleries between 2012 and 2017.

Rather than back away from them out of frustration, people who feel like museums are not representing the public they serve are increasingly taking the fight into the museums. Here are just a few of the protests that were held in museums in 2018 alone:

Brooklyn museum hiring a white woman as chief curator for its African collection

Protests of the MET changing their admission policy as classist and nativist

Demonstrators filling the Whitney to protest its vice chairman’s ties to a tear gas manufacturer

Protests at the British Museum over an exhibit sponsored by BP

Nan Goldin and P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) protesting the Sackler involvement with the Harvard Art Museums

If it’s not bad enough that the majority of work in art museums is by white males, much of the work that is not by white males was stolen during colonization. A recent report estimates that 90% of African art is outside of the continent.

Between the 1870s and early 1900s, Africa faced European colonization and aggression through military force which included mass looting of African art and cultural artifacts. This art was brought back for display in museums in European countries, as well as in the U.S. There has been increased pressure to return the stolen art back to Africa, and in 2018, we saw several protests on this front. The group Decolonize This Place took the protest to the Brooklyn Museum with signs that read, “How was this acquired? By whom? For whom? At whose cost?” and protestors at RISD demanded a sculpture looted from the Kingdom of Benin be returned.

Decolonize this Place activists protesting in the Brooklyn Museum

French President Emmanuel Macron set a new precedent when he commissioned research on how to handle France’s ~90,000 artworks from Africa. The result was a 109-page report recommending that France give back to Africa all works in their collections that were taken “without consent” from former African colonies.

France, of course, was not alone in colonization. Hundreds of thousands of African artifacts are housed in the U.K., Germany, Belgium, and Austria. The British Museum alone has over 200,000 items in its African collection. I predict pressure to return these artifacts (in the cases where they were ill-gotten) will only increase. I don’t expect people will settle for the “long-term loans” of works back to Africa that many museums are proposing in lieu of complete repatriation.

When Museums Signal Inclusion and Diversity, Good Things Happen

Museums have a lot of work to do to increase diversity and inclusion, but good things happen when they do, even when it is just symbolically.

In early 2017, Beyonce and Jay-Z shot a video for their track Apeshit in the Louvre. Before you write this off as insignificant, you should know that it had an immediate and enormous impact, with Louvre officials crediting the video for increasing their attendance by 25% from 2017 to an all-time record of ten million visitors in 2018.

No doubt Beyonce and Jay-Z resonate strongly with a young and diverse audience (with over 100 million albums sold combined), and their video likely brought some fresh faces to the Louvre.

Similarly, many of the most-heralded art exhibitions of 2018 featured female artists, suggesting a strong appetite for some diversity in our museums and galleries. These include:

Hilma af Klint - Guggenheim

Tacita Dean - National Gallery, National Portrait Gallery, and Royal Academy

Adrian Piper - MoMA

Berthe Morisot - Barnes Foundation

Anni Albers - Tate Modern

Vija Celmins - SFMOMA

Tomma Abts - Serpentine Sackler Gallery

Museums that want to see growth in attendance should follow the example set by the Louvre and others by finding public ways to signal that they are open to both artists and visitors of all races and genders, even if they still have work to do in diversifying their collections and staff. Showing some self-awareness can go a long way while en route to solving the problems long term.

Continued Pressure on Art Museums Will Drive Rapid Cultural Change That Will Transform the Art Market

The relationship between museums (as culture drivers and tastemakers) and galleries and collectors is highly interdependent. We know from studies that artists see major boosts in the market for their work when they are shown in major museum exhibitions.

“Auctions of valuable pieces tend to coincide with successful exhibitions.” Ahmed Hosny, Machine Learning For Art Valuation: An Interview with Ahmed Hosny

Given this dependency, I believe that once museums accelerate the diversification of the work they show (under pressure from an increasing number of protests), we will see the value of the art rise dramatically in the market.

We are already seeing some early signs of the market correcting for its indefensible biases. In 2019, Kerry James Marshall broke the record for top-selling work by a living African American artist when his piece Past Times sold for $21.1M at Sotheby’s last May.

Past Times, Kerry James Marshall, signed and dated '97

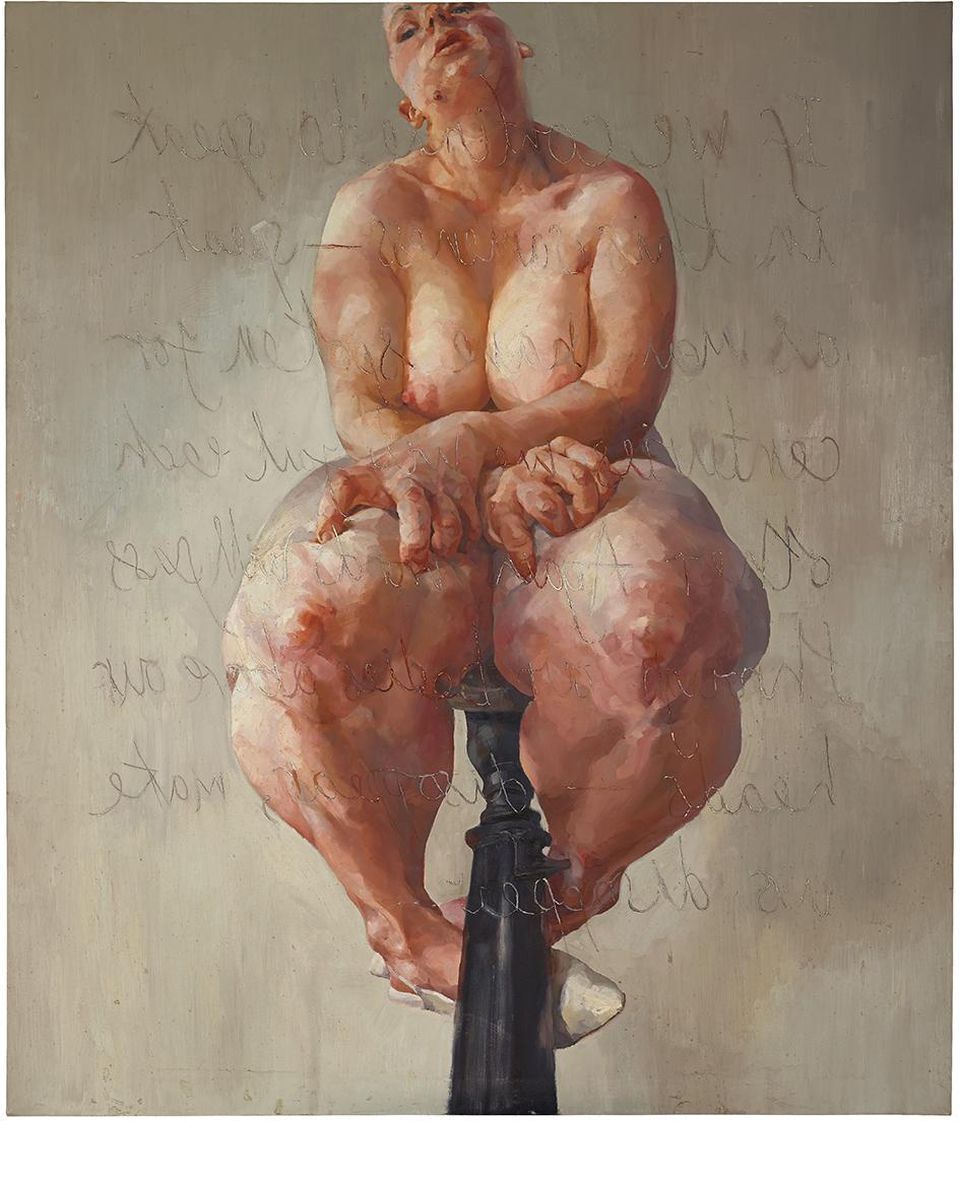

Likewise, Jenny Saville set the record for most expensive work sold by a living female artist for her 1992 painting Propped, which sold for $12.4M.

Propped, Jenny Saville, 1992

I believe these two records falling in the same year is just a very small signal of a massive market correction that will happen over the next two decades as we mature as a society and learn to see people as equals, regardless of race or gender. Those who move quickly to increase diversity will flourish, and those who don’t will risk losing their audience and becoming irrelevant.

Digital Transformation and the Dematerialization of Art

Phantom 5, 2018, Jeff Bartell

"Art is an experience, not an object." - Robert Motherwell

The second major force that I believe will shape the art world in 2019 (and for the next decade to come) is a strong trend towards embracing art + technology, and specifically around the digital transformation of art.

We are living during arguably the most dramatic technological transformation in human history, and with half the world online now, I believe the future of art is inevitably digital. With music, we saw the evolution from physical media like cassettes and CDs move to dedicated hardware like iPods and MP3 players, and then finally to streaming services like Spotify and Pandora.

Source: IFPI Global Music Report 2018

We saw the same trend in publishing, with physical books losing market share to e-books and e-readers. Those devices were just an intermediary step to streaming audiobooks, which is now the the fastest-growing sector of publishing by far.

Despite rapid shifts towards digitalization in other fields, most of us still think of canvas on a wall when we hear the word “art.” This is ironic given the fact that Americans spend an average of 11 hours a day looking at screens and almost no time looking at the walls of their homes.

Galleries are struggling or closing down precisely at a time when interest in art is rising on Instagram and at international art fairs. But increased interest does not always mean increased sales. Writer Tim Schneider captured this shift in his review of Art Basel Miami last year when he asked:

…if the fastest, and perhaps only, organically growing audience for art is more interested in being around it for a week, a few days, or even a night at a time rather than in owning it for a high price for much longer, what does that mean for everyone else?

I think we are seeing some early signs that art consumption is shifting away from physical ownership, as we saw with books and music, and toward the experiential, ushered in by the digital.

For centuries, physical ownership of art was required to enjoy it. Art was a sign of wealth and power, and collecting art was about saying “I own this art.”

LUIGI FIAMMINGO – Portrait of patron Lorenzo de’ Medici, called The Magnificent, c. 1550

With the increase in availability of the internet, we have seen a rise in social media consumption of art. Sharing selfies at museums and art fairs on social media signals your taste and sophistication without having to own physical artworks. And while a few dozen people may see the art you purchased at a gallery and hung on the walls of your home, hundreds to thousands of people instantly see the art selfies you share on your social profile. This has enabled art appreciation to be less about saying “I own this art” and more about saying “I like this art.”

Me at the Boston ICA hoping some of Albert Oehlan’s “coolness” will transfer to me in this selfie posted on Instagram

I believe as we become increasingly digital, the new message we send going forward will be “I support this artist.” As with the previous stages of “owning” and “liking,” “supporting” publicly links you back to the art and artists who you enjoy in a highly visible way. And having methods for supporting artists that do not require you to purchase or commission whole works of art greatly expands the pool of potential participants.

Few of us show off our CD collections these days; instead, we consume music through streaming and go to concerts where we take selfies and buy t-shirts that we share on social media as patronage proof points. I expect art to move in that direction, and would argue that it already has.

Physical possession of works that are created digitally provides no real advantage. Again, it is the same dynamic of dematerialization we are seeing in music and books. I gain very little by having a physical CD for every album I have access to on Spotify or a physical book for every story I have access to on Audible. Neither would be practical. With streaming, what I have lost in fetishizing tangible objects, I have gained with access to a number of albums and books nobody could have dreamed of 25 years ago.

Does an art streaming service in the mode of Audible or Spotify sound ludicrous? Well, generation one of art streaming has been around for almost a decade and has over one billion users.

I’m talking about Instagram, of course. But Instagram is really just the Napster of art streaming, as it falls short of supporting most artists. Nevertheless, it is a solid proof point of our insatiable appetite for the digital consumption of art. I predict we will soon see a combination of the proven distribution and consumption model of Instagram paired with patronage models like Patreon and Kickstarter.

Last year, we saw a lot of experimentation around new models for funding artists from several promising startups exploring blockchain. Dada.nyc, where I am an advisor, has over 160K registered artists in their community. Over 100K drawings have been produced in their social media platform where artists communicate with each other through drawings.

I started this drawing when I was in bed with Lyme disease in my knee. Artists from around the world responded. The conversation continues months later.

The Dada team is carefully working through how to create a market that does not just duplicate the current physical art market. They want to avoid building a system where only a few can afford to collect and an even smaller number of people are rewarded for their creative work. Dada dislikes the collecting of art as speculation and is constantly evaluating new models of patronage that can enable artists to focus on creating their work. Their goal is for the entire community to benefit each time patrons provide monetary support and to blur the lines between “patrons” and “artists,” as they believe creating art is beneficial for everyone.

Another blockchain art market that experienced significant traction and growth in 2018 is SuperRare. They provide a new revenue stream for artists (which helps fund creative projects) while giving patrons the ability to discover, buy, sell, and collect unique digital creations by artists from around the world.

Screenshot of my digital art collection in SuperRare

SuperRare completed almost 6,000 transactions, generating 602.76 ETH to date (over $70K) in less than a year since their launch.

https://www.dapp.com/dapp/SuperRare

Sure, these are not Instagram numbers just yet, but having a handful of startups (others notables include, Portion.io, Known Origin, R.A.R.E. Art Labs, and Digital Objects) prove out the model is an important first step in building out any new market. It is also telling that despite the cryptocurrency crash, which devastated the majority of blockchain companies, all of these blockchain art markets are still in business and experiencing growth.

There are two important things to note about digital art markets like the ones above:

You don’t need to own the work to experience it. When I buy a work on SuperRare, I see the same image that everyone else can see for free.

Because of this, the joy in collecting digital art does not derive from denying other people access to art, but instead, in increasing access to art and artists you enjoy and want others to appreciate, as well.

Digital art is highly replicable and transmissible, so there is no benefit to keeping it to yourself. In fact, the value of the work (as with all art) only goes up as you share it more broadly. The message with collecting in a digital age is less and less “I want you to know how powerful I am - I own this thing that nobody else can own” and is instead “I want you to know I support this artist because their work is awesome, and I’m excited to share it with as many people as possible.”

So why buy digital art if everyone else can see the same image for free? It’s simple: Because you can’t expect artists to continue creating if you don’t support them. I believe it’s not the art itself that we should revere, but the people making it. Too often we celebrate and fetishize individual works of art long after the geniuses that created them have died penniless. Rather than cater to speculative or extrinsic values, I predict we will see several new digital art streaming services built on the intrinsic pleasure we derive from art. We’ve learned we don’t need to own a physical, re-sellable book in order to enjoy a great novel, or a piece of vinyl to appreciate music. The same will be true for art.

It is important to remember that ownership and speculation on the part of collectors is not a necessary ingredient to producing great art. That is just one way of making sure artists have enough money to survive and continue working, and there is a good chance it is not the most effective (nor the best) model for artists.

Of course, many artists will choose to continue to work in traditional physical media like painting and sculpture. We will always have amazing museums full of physical artwork, and I couldn’t be more thankful for that. There will always be galleries for buying and selling physical art, same as we still have brick-and-mortar bookstores and music stores. But I think the digital transformation of art is inevitable and coming faster than most people expect. I also strongly believe that this shift is healthy and presents an opportunity to reframe (pun intended) how we treat artists and consume art.

Summary and Conclusion

Lots of people I know don’t like making or reading predictions. The primary complaint I hear is that predictions are either “boring and accurate” or “entertaining but outrageous.” I, on the other hand, love making predictions. I feel like the process is similar to making art in that I can use both my imagination and my powers of observation and reasoning to show the world how I see things as they could be.

As a pseudo-futurist and techno-optimist, I relish the idea that we can build a world where an increasing number of people can participate in the joys that art has given me in my life. I believe the macro forces and trends that I am seeing in the world support that idea.

But I don’t want to let myself off the hook too easily here, so what am I actually saying that is measurable here in terms of predictions?

First, a “Moore’s Law” in diversity in art. Inclusion and diversity in art will double annually until we reach parity, as measured by:

An increase in the price of works sold by women and minorities at auction;

An increase in the number of women and minorities in positions of power at museums and in the art trade;

Second, an increase in the number of people interested in art without a corresponding increase in the number of collectors;

Third, the launch of at least one art streaming service in 2019 and a shift towards this model over the next decade;

And fourth, a shift from artists, art journalism, and art fairs to diversity and tech as the key topics for all of 2019.

I hope you enjoyed this year’s predictions! Whether you agree or disagree, I am always excited to hear from Artnome readers. Leave your thoughts in the comments below or hit me up on Twitter at @artnome or e-mail me at jason@artnome.com.