Machine learning is at its best when used as a tool for augmenting human capabilities, not for replacing them. And while we may not all be able to build our own machine learning models from scratch, new tools like Runway ML and Joel Simon’s forthcoming Artbreeder are opening up access to these machine learning models for everyone. Will this flood our screens with infinite images of deep kitsch? Or can machine learning augment human creativity on a larger scale and point towards a new direction for art?

My most important mentor, my high school art teacher Marco Marchi, taught me that creativity can start with new tools, but it should never stop there. This is especially true with machine learning models that can apply eye candy like filters at the push of a button, only then to devolve into derivative and contrived visual effects.

Marco also taught me that the beauty in making art is in the discovery process. Likewise, art appreciation is about unpacking the artist’s discovery process and finding your own discoveries along the way.

The future of work according to The Jetsons

There is not much discovery in pushing a button to apply a single filter or machine learning model, nor is their much to unpack, but I believe it can be a starting point for a more interesting artistic journey if used as a tool for augmentation.

Marco passed away recently, and I have been thinking about him a lot and revisiting his work. Over the weekend I played around with style2paints, a machine learning model for colorizing sketches, and tried it on several of Marco’s sketches.

Earth Gift, pen and ink drawing by Marco Marchi

Earth Gift, pen and ink drawing by Marco Marchi, colorized in style2paints

I wondered what Marco would have thought of these new machine learning tools. I decided that he would approach them with with openness and curiosity rather than judgment and suspicion. With that in mind, I decided to do the same. In the rest of this article, I take style2paints for a spin documenting and sharing my creative process along the way while trying to discover if machine learning for the masses will augment creativity, produce more kitsch, or both.

AI as a tool for augmenting creativity and introducing unpredictability

After playing with Marco’s ink drawings, I decided to run other images with simpler compositions through style2paints to try and learn its quirks and breaking points. Etchings and drawings from online databases like the MET’s open access collection provided me with plenty of interesting fuel.

Portrait of Charles Meryon, 1853, Félix Henri Bracquemond,

Portrait of Charles Meryon,, updated in style2paints

I pretty quickly figured out that recognizable images with fewer details and less shading actually produced the most realistic outcomes. But the most realistic results are rarely the most interesting.

I find breaking tools is the fastest way to get to their creative potential. By playing with a combination of filters for hue, brightness, and grayscale in Runway ML, I was able to break the style2paints model a bit.

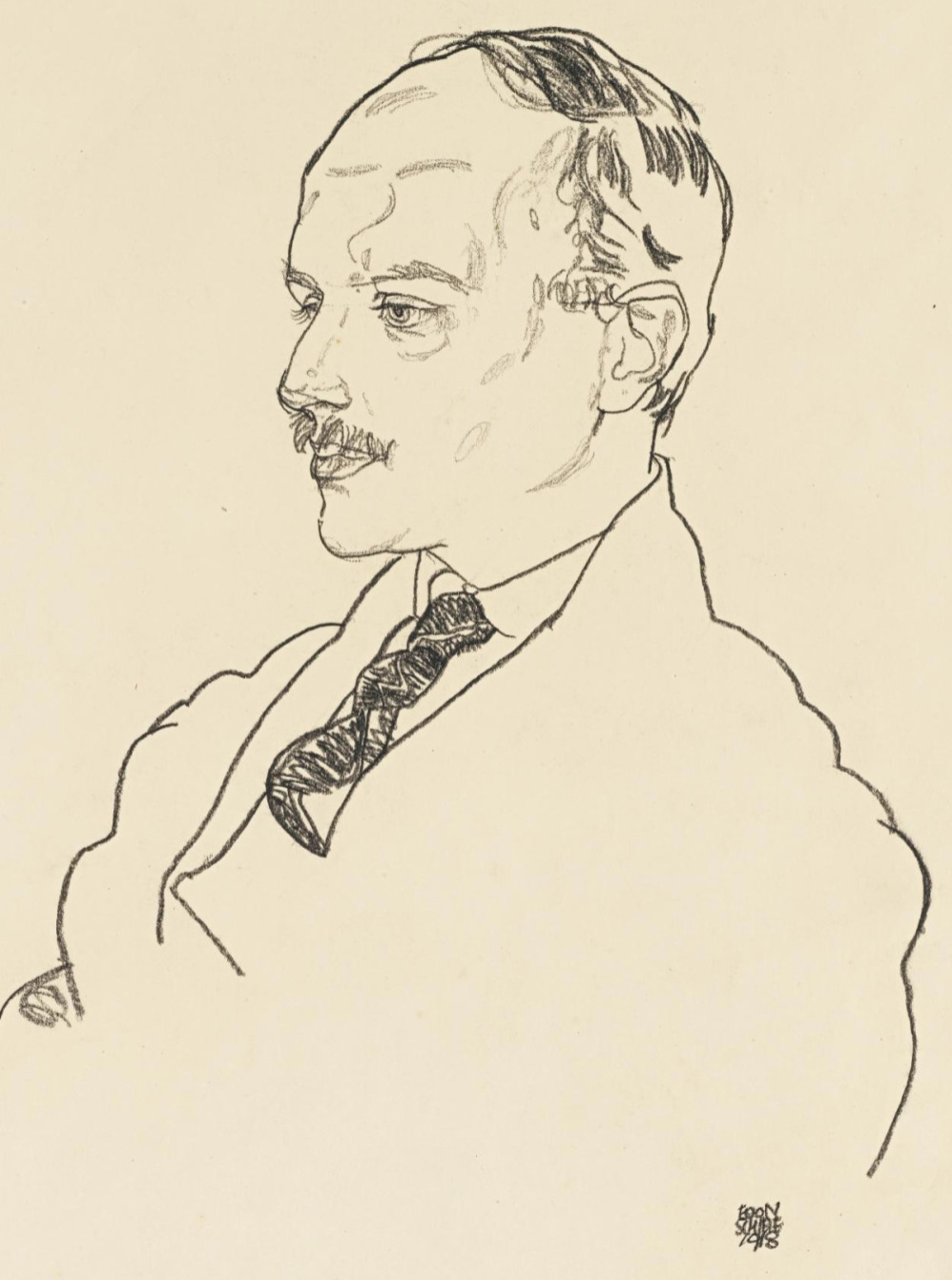

Portrait of Guido Arnot 1918 by Egon Schiele

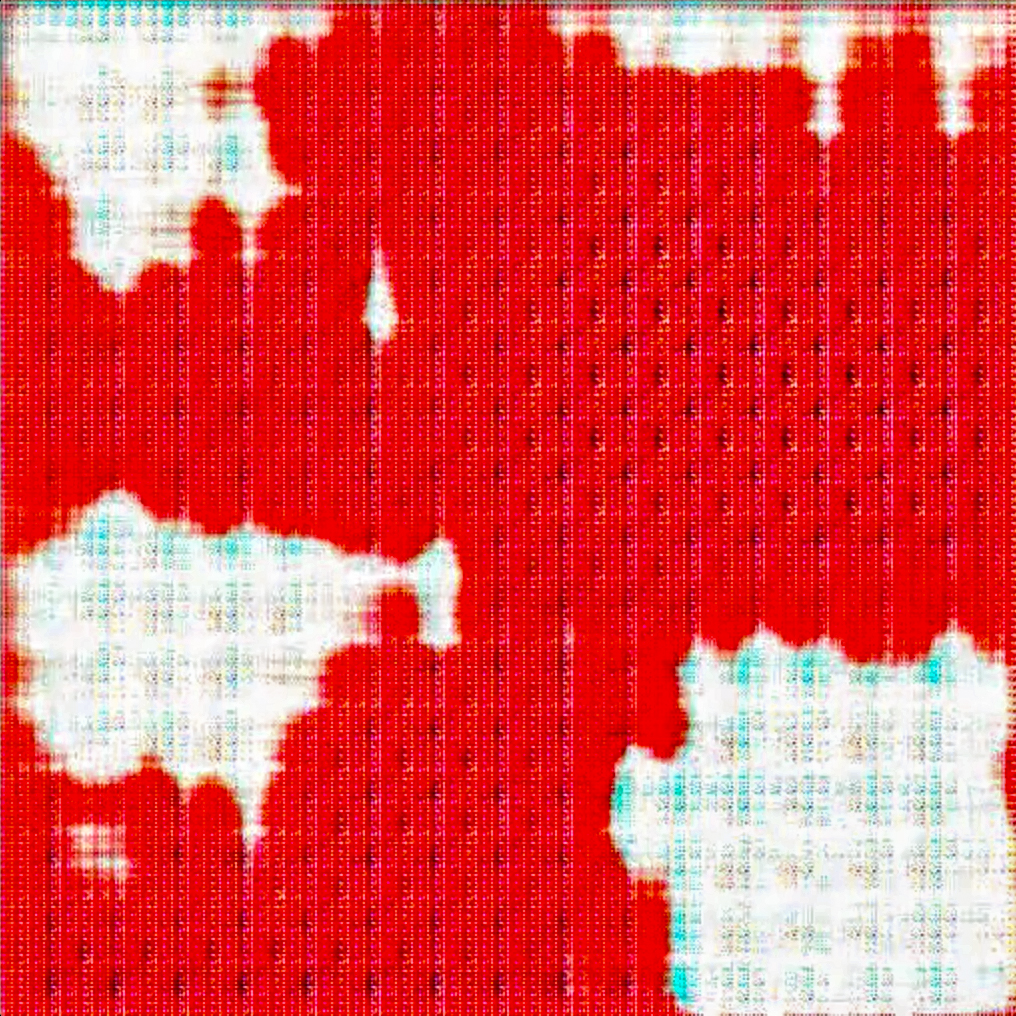

Portrait of Guido Arnot, updated in style2paints

There are known problems with machine learning models showing skin tone bias in favor of lighter-skinned people sometimes called “whitewashing” (this is due to disproportionate or biased training data skewed towards caucasians). With certain filter combinations in Runway ML you can actually approximate the reverse effect and produce a wider variety of skin tones as seen in these Egon Schiele drawings.

Standing Nude Facing Right, 1918, Egon Shiele

Standing Nude Facing Right, updated in style2paints

I then tried some more unusual subject matter as an input to see if I could break the model that way - for example, Thomas Rowlandson’s Comparative Anatomy, which comically compares the human head to that of an elephant and a bull.

Comparative Antomy, 1800-’25, Thomas Rowlandson

Comparative Antomy, updated in style2paints

I loved the results from these cartoonish images. It seemed the less details I provided the model and the less realistic the characters, the more interesting the results were.

I thought about other sources for simplified minimalistic inputs like cartoons and coloring books. Pretty quickly I wondered what I could get by grafting coloring book images onto historic etchings?

I started in Photoshop, but the results were a bit disjointed. I then I printed the images out and drew on them directly using pen and marker to unify the images and to make them my own, and then re-ran the model.

Drawing directly on the printouts by hand was producing the most interesting results. Eager to explore, I made a quick dumb sketch of a monster staring at Homer Simpson to see how the model would handle it.

To my surprise, it produced a pretty compelling ghost from my crappy doodle.

I now had an image that felt really satisfying and unique. Sure, it is not going to the Louvre anytime soon, but I was developing a visual language and an understanding of the tool that gave me some control while leaving a delightful amount of unpredictability.

I also really liked the idea of blending of highbrow historical etchings from the MET database with lowbrow cartoons from children’s coloring books. I tried a few others, including a mash up of a Picasso drawing and Garfield I called Picarfield.

Picarfield Glitched, Jason Bailey, 2019

The clean version of Picarfield was kind of boring. But once I started breaking the model a bit more, it produced some glitchy versions full of artifacts, which I actually like in this case.

I often find running towards things that repel you and exploring them more deeply is a great trick for prompting creativity. One of my favorite painters, Albert Oehlen, is a master at this. In a recent interview Oehlen shared:

If someone stands in front of one of my paintings and says, 'This is just a mess', the word 'just' is not so good, but 'mess' might be right. Why not a mess? If it makes you say, 'Wow, I've never seen anything like that,' that's beautiful.

Ohlen’s Computer Paintings transform the Mac paint/inkjet aesthetic into high-art.

Albert Oehlen’s Prix Ars Electronica (1991)

I ultimately decided creating analog work to feed into the model was the more interesting direction. Introducing handmade images feels like a good way to fight back against the often cookie-cutter output of machine learning models. I made a super creepy contour drawing of my wife (sorry, sweets, you don’t really look like this) and ran that through style2paints.

And then “put a bird on it”… just because.

To redeem myself, I did a few more accurate (and flattering) life drawings of Erin. I found it more than a little ironic that playing with AI models on my computer had lead me to do some life drawing for the first time in years.

In the end I didn’t create any masterpieces (there is a reason I spend more time writing than making art these days), but the process was an adventure, and the more I experimented, the closer I got to making interesting work. I think process and exploration is the secret sauce that makes any art interesting.

The reason I admire and write about artists like Helena Sarin, David Young, and Robbie Barrat so regularly is that they are going beyond simply applying models: they are deeply exploring the creative process, and it shows in their work.

Pocos Frijoles, an artisan coffeeshop, Helena Sarin

Nude Study, Robbie Barrat, 2019

Robbie recently looked to traditional methods of artistic training as part of his process, sharing “I’m trying to get better at using neural networks for making artwork by engaging in more traditional exercises (figure drawings this time).”

(b62a,unknown01,1) from the Tabula Rasa series, David Young, 2019

David Young breaks down machine learning models to the fewest possible components as a way of “revealing the materiality of AI.” As he describes them on his site, “These images are an exploration of how a machine learns. They were generated from no more than a handful of training images.”

All three artists use machine learning models to make art, but they could not be more different. That is because the tools are only a starting point - it is their process which makes their work rich and unique.

On the opposite side of the spectrum we have “artists” giving their machine learning models human names and putting wigs on robots to reinforce disingenuous claims that AI is replacing human artists. This is sad, as art has great potential to educate an anxious and confused public on the actual capabilities of machine learning. When the AI hype dies down and we head into the next AI winter, we should see fewer uninformed dystopian AI art projects. These projects will thankfully be lost to history while those using AI and ML as a tool instead of subject matter should continue to grow and break new ground.

I am also optimistic that with Runway ML and Artbreeder, we will see some more traditional (analog) artists bringing deeply established creative process to these new (digital) tools. Those more traditional artists may not have the technical chops to train their own machine learning models, but I am hoping that a rich sense of artistic process will expand the work that we see being created today into new and exciting directions.

This article was written in loving memory of my high school art teacher Marco Marchi. Marco gave purpose to the lives of thousands of students by being a friend and mentor and teaching us to think creatively, independently, and to challenge the status quo. The idea that I could someday be like him when I grew up helped me make it through high school and into college. Rest in peace, Marco.